Debt, Great Recession and the Awful Recovery

Debt has been reviled at least since biblical times, frequently for reasons of class (“The rich rule over the poor, and the borrower is slave to the lender.” Proverbs 22:7). In their new book, House of Debt, Atif Mian and Amir Sufi portray the income and wealth differences between borrowers and lenders as the key to the Great Recession and the Awful Recovery (our term). If, as they argue, the “debt overhang” story trumps the now-conventional narrative of a financial crisis-driven economic collapse, policymakers will also need to revise the tools they use to combat such deep slumps.

What makes debt such a large macroeconomic risk? What is the evidence for a debt-driven (rather than intermediation-driven) slump and weak recovery? Was the crisis of U.S. financial institutions a dramatic sideshow? Would replacing debt contracts make the economy less prone to such disruptions? Would it be worth the cost?

To avoid bankruptcy, debtors must pay regardless of economic and financial conditions. Only in bankruptcy do creditors bear a burden of adjustment to adverse shocks to borrowers – and then all at once. Among households, net debtors typically have less income and wealth than lenders. That’s why they borrow in the first place. But being more leveraged, they also are more likely to cut spending in bad times. [Technically, they have a higher marginal propensity to consume (MPC) out of additional income.]

If an adverse shock hits enough debtors at the same time, a synchronized pullback can trigger a recession. If their debt-driven demand previously boosted asset prices above sustainable levels, a vicious cycle of retrenchment, job losses, bankruptcies, fire sales, and plunging asset prices can turn a recession into a depression. The spillovers (or externalities) hit everyone in the economy, including those who are not leveraged.

But vicious cycles make it difficult to distinguish cause and effect. In the run-up to the Great Recession, did rising house prices boost debt to unsustainable levels, or vice versa? What was the relationship between housing losses, household spending, and jobs?

House of Debt is at its best in showing that: (1) a dramatic easing of credit conditions for low-quality borrowers fed the U.S. mortgage boom in the years before the Great Recession; (2) that boom was a major driver of the U.S. housing price bubble; and (3) leveraged housing losses diminished U.S. consumption and destroyed jobs.

The evidence for these propositions is carefully documented using detailed geographic data. In zip codes where less-qualified borrowers (with lower incomes and wealth) were relatively numerous and gained access to mortgage credit, housing prices rose far more sharply than elsewhere. Prices in those places then plunged further when the nationwide bubble burst. Residents in those same zip codes also exhibited disproportionally large declines in their consumption of durables (like autos). And service-sector employment driven by local demand fell more than elsewhere. What went up came down with a thud.

The strong conclusion is that – as in many other asset bubbles across history and time – an extraordinary credit expansion stoked the boom and exacerbated the bust. Of that we can now be sure.

What is less clear is that these facts diminish the importance of the U.S. intermediation crisis as a trigger for both the Great Recession and the Awful Recovery. As evidence of causality, House of Debt emphasizes: (1) the housing downturn preceded both the financial crisis and the plunge in business investment; (2) the consumption downturn was deep, reflecting leveraged losses; (3) the liquidity crisis was over in a few months; and (4) weak demand (rather than weak supply) drove the weakness of lending in the recovery.

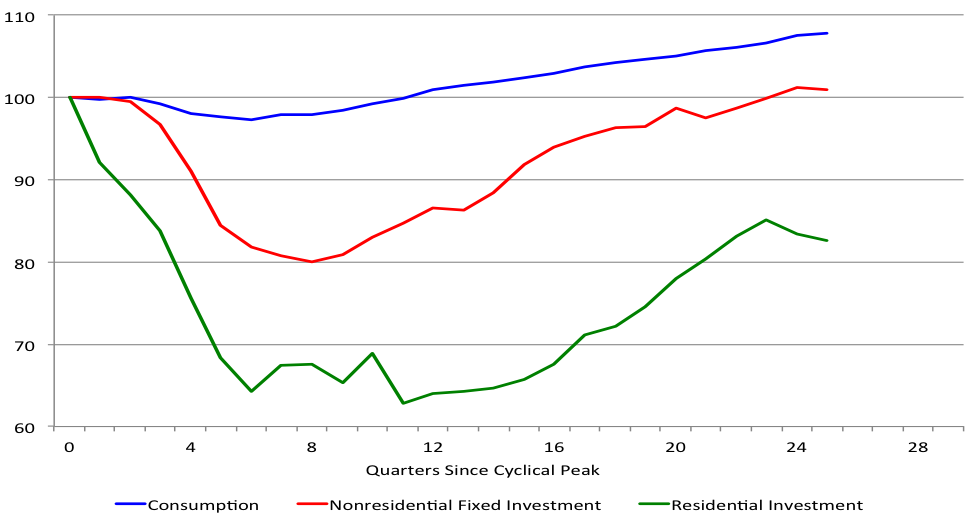

Yet, while the U.S. recession started in the final quarter of 2007, it turned vicious only after the September 2008 failure of Lehman. The two quarters beginning October 2008 saw the deepest U.S. economic plunge in any six-month period in more than 50 years. Moreover, the damage to U.S. credit supply lasted far longer than the urgent phase of the financial crisis: according to a large survey of small firms, credit availability returned to pre-recession standards only as of 2013. Finally, while the consumption decline was deeper than in other post-World War II recessions, the weakness of investment arguably has become the defining characteristic of the Awful Recovery (see chart below).

Real GDP Components Indexed from Cyclical Peak (4Q 2007=100)

Source: BEA and FRED

What about the remedy? Would greater debt forgiveness have limited the squeeze on households and reduced the pullback? Almost certainly. Forgiving debt transfers resources from households with a low propensity to consume to those with a higher one. As frequently observed in history, debt writedowns can serve the interests of both lenders and borrowers by reducing the deadweight losses associated with bankruptcy and foreclosure. House of Debt argues compellingly that the securitization of mortgages (including contractual clauses that required unanimity among investors) made it exceptionally costly for lenders and borrowers to coordinate such “optimal” debt writedowns.

What about preventing a future Great Recession? House of Debt calls for new financial contracts that place the burden of bearing the risk of house price declines primarily on wealthy investors (rather than on borrowers) who can better afford it. In exchange for taking on a large share of the downside risk, investors (they are more than just lenders!) also would share in the upside by receiving a portion of the capital gains when houses are sold. Such risk-sharing contracts, which have previously been advocated by other economists, would reduce the potential for households to bear the full force of leveraged losses.

But who would bear the housing-price risk in a world with such contracts? Putting assets that are so sensitive to housing prices on the balance sheets of banks or shadow banks could easily increase systemic risk in the same way that the origination and retention of subprime mortgages did in 2007. If housing finance is to work this way in the future, regulators would have to keep (shadow) banks out of the mortgage business. That leaves open the question of whether wealthy investors (and less run-prone intermediaries like pension funds and insurance companies) have sufficient demand for housing-price risk to satisfy the financing needs of qualified, would-be homeowners.

The discussion about remedies to debt and leverage cycles is still in its infancy. House of Debt shows why that discussion is so important. Its contribution to understanding the Great Recession (and other big economic cycles) will influence analysts and policymakers for years, even those (like us) who give much greater weight to the role of banks and the financial crisis than the authors.