Do U.S. Households Benefit from the Great Moderation?

Something odd has happened to the U.S. economy over the past 30 years. Aggregate income (measured by real GDP) has become more stable (even including the 2007-2009 Great Recession). But, at the household level, the volatility of income has gone up. Put differently, families face greater income risk than in the past despite generally fewer or smaller economy-wide wobbles. What should we make of this?

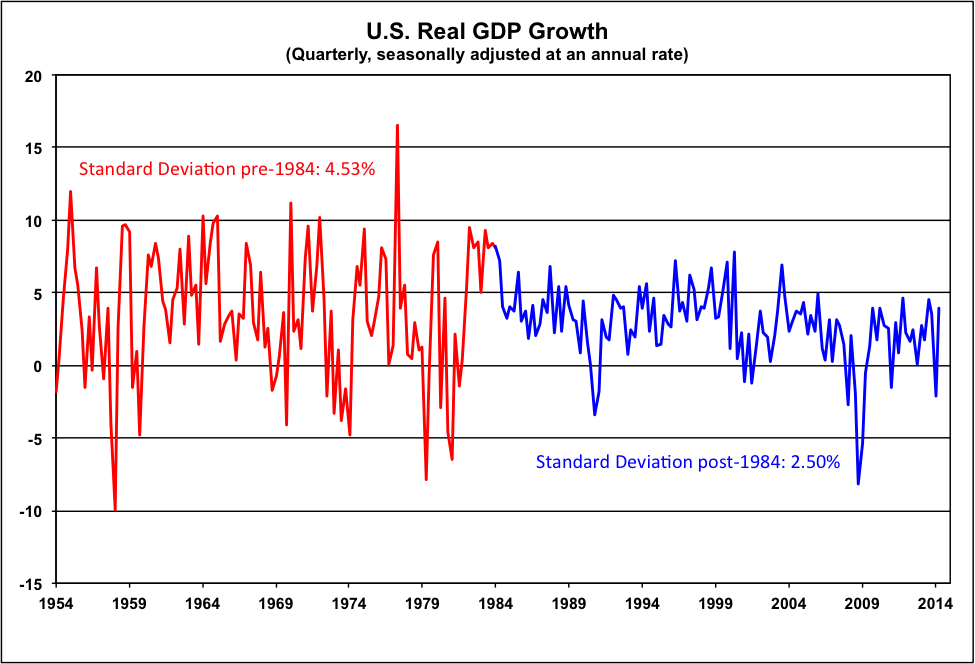

Let’s start with the facts. In the picture below, you can immediately see the primary evidence for the Great Moderation. The standard deviation of quarterly GDP growth fell by nearly a half beginning in the mid-1980s; something we have known since the last 1990s. (You can find the original paper pointing this out here.)

Source: FRED

This stability reflects several factors, including improved inventory management policies, better risk sharing through financial markets, more international openness and improved monetary policy; as well as just luck. And, most people think this is a great thing. (You can find a summary here.)

What does this aggregate stability mean for households? To see the implications, think about an example where economic growth slows by 2½% – roughly the size of an average U.S. recession in the past half century. If that meant that everyone temporarily went home an hour earlier on Friday afternoon, we wouldn’t care all that much. But that’s not how it works. Instead, one in every 30 or 40 people lose their jobs. The pain of a business-cycle downturn is concentrated, not widely shared.

That is, there is substantial idiosyncratic risk out there. Employment and income at the level of individuals and households turn out to be very volatile. And, much to the dismay of most people that know about it, this micro-level income risk has been rising despite greater macro stability.

One study by Dynan, Elmendorf and Sichel highlighted this micro pattern in a figure that we reproduce below. There are two things that are striking about this chart (which shows the standard deviation of percent changes of real household income): the level and the trend. Measured this way, income volatility has risen from an already high 38 percentage points per year (!) in the early 1970s to an even higher 50 percentage points in 2008.

Source: Dynan, Elmendorf and Sichel, "The Evolution of Household Income Volatility," The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, De Gruyter, vol. 12(2), pages 1-42, December 2012.

What is going on?

Before we get carried away, it is important to understand that the increase in the volatility of household income could mean a variety of things, only some of which we should care greatly about. The first step in figuring out whether we should care is to understand whether the increased variability in income is coming from permanent or transitory movements. Put another way, when someone’s income falls, does it tend to rise quickly back to where it was, or does it stay low? Researchers who looked into this conclude that both have increased. That is, there have been increases in income volatility resulting from job turnover as well as an increase related to shifts in the types of jobs that are out there. At least some of the increase in idiosyncratic risk comes from the fact that people who lose their jobs are less likely to find a new one at the same level of pay. That’s a permanent and painful shock; one that we definitely care about.

The point is that, as aggregate (or systematic) income risk has fallen, idiosyncratic income risk has gone up. There is a chance that these two phenomena have the same underlying cause. For example, a pickup in the speed at which firms respond to changes in technology, raw material costs, and the like, could reduce aggregate volatility, but raise job turnover and employee income variation along with it.

Regardless of the cause, a key question is whether households can insure themselves against heightened income risk, or at least the part that is longer term. At first glance, a large group of people facing uncorrelated risks would seem to be perfect candidates for an insurance pool. The point is that while some people’s incomes go up and some go down in a given year, the average change is small, steady and predictable, allowing for risk pooling.

In practice, however, there are important income risks for which insurance is not readily available and for which financial markets do not offer households the opportunity to hedge. Consider, for example, those unfortunate persons who have been trained to work in a job or an industry that disappears for whatever reason (say, because of new technology). Can they stabilize their income stream by fully hedging such “livelihood” risk? The answer is no.

Why not? We see three interrelated problems that would have to be overcome before markets would offer such insurance on a broad scale. They have to do with incentives, complexity and cost. Someone who is hedged against livelihood risk has less incentive to seek re-training (or a new job if they lose one). While insurers know how to overcome such incentive problems, doing so usually requires the insured to bear part of the risk. It also creates complexity that makes the insurance or the risk hedge less attractive (think of the scary fine print!). Finally, there is the cost of doing all of this. Creating and operating financial markets and institutions needed to hedge risks is costly. Imagine, for example, a suggestion made by Robert Shiller several years ago: “livelihood insurance contracts.” To have a market actively trading such contracts, you would need a large number of them covering a broad array of professions to ensure diversification of the risk. And, what happens when new jobs and new sectors come into existence?

Where does all of this leave us? The answer is that U.S. households face substantial idiosyncratic risk in their incomes – even more than they faced several decades ago. This poses an ongoing challenge to finance specialists and to economic policymakers: can financial institutions and markets facilitate a better sharing of these income risks? Which financial innovations would help and also prove economically viable? And, where complexity is unavoidable, can we educate people about new mechanisms to hedge these risks?