ECB Paddles Both Ways in the Rubicon

On January 22, the ECB crossed the Rubicon twice – but in opposite directions. In an effort to combat deflation and years of anemic growth, the central bank announced a sustained program of large-scale asset purchases. At the same time, it capped the amount of risk-sharing in the Eurosystem. Other central banks have done the first, but not the second. And, while outright balance sheet expansion helped ease euro area financial conditions somewhat, the limit on risk-sharing works in the other direction. Rowing toward both shores at the same time doesn’t move a boat far or fast.

We will try to explain both the mechanics and the implications of each aspect of this new policy. Starting with the balance sheet, the key change is a shift from a system in which the size was determined by banks’ demand for reserves to one in which it is set by the ECB’s supply. As we described in an earlier post, since October 2008 the ECB has allowed banks to obtain whatever quantity of reserves they wished at a policy rate set by the Governing Council. (This “fixed-rate full allotment” approach was part of the ECB's principal “refinancing operation” that provided reserves in exchange for eligible collateral.)

The red line in the following chart depicts the evolution of the Eurosystem balance sheet under this demand-driven regime. Assets peaked at €3 trillion in mid-2012 at the height of the euro crisis. This was a time when banks in the periphery had virtually no source of funding aside from the ECB. European financial markets were fragmented to the point where funds were flowing from countries under stress to countries seen as more safe in order to hedge the possibility of a euro-area collapse. The recipients of the flight capital, rather than lending to peripheral banks, were all going to the ECB demanding reserves. (This is related to the movements in TARGET2 balances, which we have described here.)

The balance sheet decline since 2012 has several causes, none of which include any ECB decision regarding the supply of reserves. First, and most important, President Mario Draghi’s 2012 pledge to do “whatever it takes” to save the euro reduced redenomination risk – the risk that a euro-area breakup would result in national versions of the euro, some more valuable than others. That helped reverse the deposit flight. Second, the 2014 asset quality review and stress testing of banks, combined with the centralization of bank supervision in the Single Supervisory Mechanism, improved trust within the financial system. (See this post.) And finally, the move to a negative deposit rate (currently -0.20%) meant that banks had to pay the ECB for the privilege of depositing their excess reserves.

ECB Balance Sheet (Billions of euros), 2007–September 2016F

F forecast. Source: ECB and authors' estimates.

At this writing, the consolidated balance sheet of the Eurosystem stands at €2.158 trillion. In the absence of any policy actions, this number will continue to fall as past long-term refinancing operations (LTROs) expire. The dashed black line (our forecast) shows the decline of roughly €200 billion that we expect to see over the next two months. In addition, over the next two years, a portion of the €144 billion currently held as a part of the Securities Market Program (SMP) will mature. If the recent pace of SMP decline persists, these holdings will fall by perhaps €75 billion. (We are guessing here, since the ECB does not disclose the maturity of SMP assets.)

This brings us to the most recent policy decision. The ECB Governing Council has announced its intention to purchase €60 billion in securities per month from March 2015 through September 2016 (or until there is a “sustained adjustment in the path of inflation”). For the specified period of 19 months, that corresponds to a total of €1.14 trillion. By our reckoning, this will bring the Eurosystem’s total assets to a level slightly below, but close to, the 2012 peak of €3 trillion. Of course, the open-ended commitment may well lead to a further increase after September 2016.

Importantly, the new policy shifts the ECB’s operational framework dramatically from one where the banks determine the level of reserves themselves to one where the ECB decides how much the banks will be forced to hold. This supply-driven approach is what the Federal Reserve, the Bank of England and the Bank of Japan have been doing for years – they first force the short-term interest rate to zero, and then expand the supply of reserves even further. This has become the common definition of quantitative easing (QE).

Will this work to reignite growth and push inflation back up toward the ECB’s “close to, but below 2%” objective? Possibly. In his press conference, President Draghi described two mechanisms that should help achieve this goal: (1) a portfolio effect, where investors who sell low-risk assets to the central bank replace them with higher-risk assets; and (2) a signaling effect, where policymakers increase their commitment to keep interest rates low in the future. Both would drive asset prices higher, raise wealth, and promote private spending. To these, we would add: (3) an exchange rate effect, whereby policy accommodation pushes down the value of the currency; and (4) a collateral effect, in which the value of potential borrowers’ assets rises, making them more creditworthy.

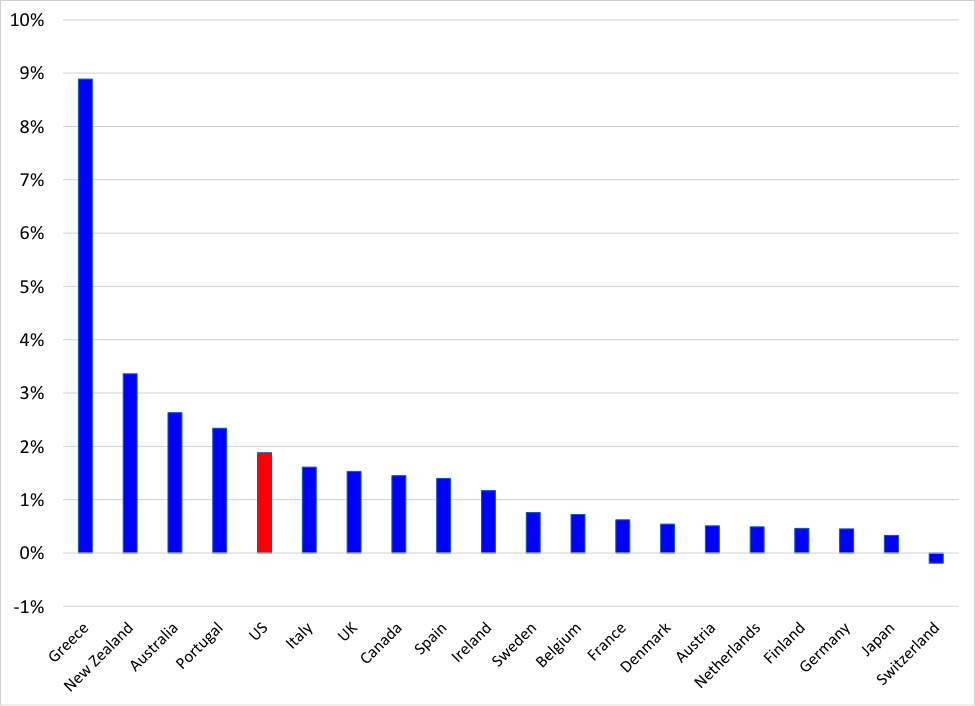

Are these likely to be potent in the euro area today? As European officials are fond of saying, most financing there is through banks – not through capital markets – limiting the impact of rising asset prices. As for collateral quality, this improves when interest rates fall, but interest rates at all maturities are already extremely low throughout most of Europe. In fact, as shown in the chart below, with the exceptions of sub-investment grade Greece and Portugal, the yields on all 10-year euro area sovereign bonds are lower than U.S. yields. Partly as a result, the depreciation of the euro is widely seen as one of the most important channels for transmitting ECB policy easing at this time.

10-year government bond yields, January 22, 2015

Source: Thomson Reuters

Perhaps there will be a positive surprise. As Federal Reserve Board Chairman Bernanke once asserted, “The problem with QE is that it works in practice but it doesn’t work in theory.”

Yet, the ECB’s other unprecedented move adds considerably to our doubt. As we said at the outset, there are two parts to the January 22 announcement – “conventional” QE, as just described, and a limit in the degree to which national central banks (NCBs) will share the risks arising from the purchase of the securities. The second is new, and quite troubling. At the press conference, President Draghi did his best to minimize its importance, but we are not convinced.

First, the technicalities. The Eurosystem has rules for how to handle losses. Generally, if there is a loss arising from the default of a counterparty in the regular monetary policy refinancing operations, these are shared in proportion to the capital the countries have paid in to the ECB. There was such a loss in the Lehman bankruptcy, and it was shared. Such loss sharing also would apply to the bonds that are currently held through the various purchase programs that exist today. The exceptions are those cases designated by the ECB as Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA), in which an NCB may provide an exceptionally large volume of lender-of-last resort funding that is not part of the single monetary policy. The risks of ELA lending, which occurred in several peripheral countries during the crisis, are borne by the NCB (and its fiscal authority).

This is changing. Quoting President Draghi:

“With regard to the sharing of hypothetical losses, the Governing Council decided that purchases of securities of European institutions (which will be 12% of the additional asset purchases, and which will be purchased by NCBs) will be subject to loss sharing. The rest of the NCBs’ additional asset purchases will not be subject to loss sharing. The ECB will hold 8% of the additional asset purchases. This implies that 20% of the additional asset purchases will be subject to a regime of risk sharing.”

ECB President Mario Draghi, “Introductory statement to the press conference,” 22 January 2015.

To see what this means, we can do a quick computation. Today, the entire balance sheet is subject to risk sharing. That’s €2.16 trillion. If our projections are accurate, by September 2016 the amount subject to risk sharing will be €2.13 trillion. Or, possibly, less, if the assets to be purchased include those on which fiscal risk-sharing already takes place (for example, the debt of the European Stability Mechanism). In other words, the ECB’s planned QE will leave the Eurosystem’s mutualized risk at or below where it is today. This seems unlikely to be an accident.

In the run-up to the January 22 announcement, some observers opined that the refusal to share risk would imply a lack of European solidarity. From our perspective, the problem is that capping risk-sharing is a major step away from a seamless pan-European financial market and toward the renationalization of monetary policy. Our prime concern is that depositors and investors will view the refusal on the part of European governments to mutualize sovereign risk (which is what this is) as a refusal to share financial system risk as well. This, in turn, would revive redenomination risk.

Initially the ECB’s announcement has improved financial market conditions, including somewhat lower bond yields, a rising stock market, and a falling euro. Yet, if we are right, then the risk-sharing arrangement undoes at least some, if not all, of the stimulative impact of QE. President Draghi said that funds flowing into German debt are fungible and can find their way to other euro-area countries. But, will funds in German banks find their way to peripheral banks? In the absence of an unlimited commitment to share banking system risk in the euro area, how much will German banks lend to Italian or Spanish banks, much less Greek banks?

As we have heard European officials say in the past, everything in Europe is messy. To that, we would add that rowing in both directions can leave you drifting in the middle of the river.