Inflation and Fiscal Policy

Why is it proving so difficult to raise inflation? For generations after World War II, this was not something that worried economists. Yet, today, even as central banks lower policy rates close to zero (or below) and expand their balance sheets beyond what anyone previously imagined possible (see chart), inflation remains stubbornly below target in most of the advanced world.

Central Bank Assets (Percent of GDP), 1999-2Q 2016

Note: The final observation for the euro area is 1Q 2016; the final observation for Japan is based on assets through May 2016. Sources: FRED, Japan Cabinet Office authors’ estimates for final observations.

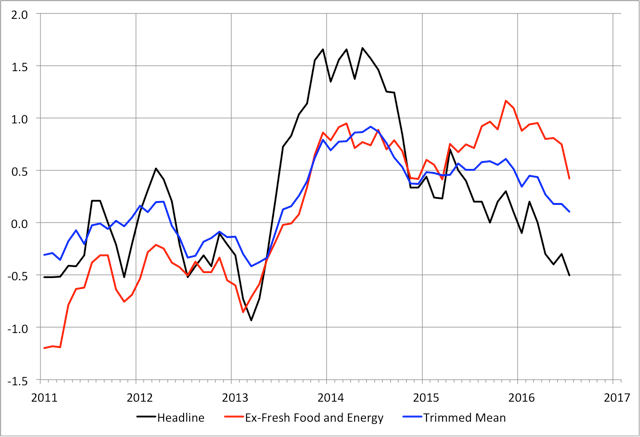

Nowhere is this problem more profound than in Japan, where mild deflation was the norm for nearly two decades and where inflation still remains well shy of the Bank of Japan’s 2% target. Even as monetary policymakers expanded the central bank’s balance sheet by nearly one-third of GDP and nudged its policy rate slightly below zero, consumer price inflation (as measured by our preferred trend measure, the 10% trimmed mean) has slipped from 0.9% to 0.1% over the two years to July 2016 (see chart)!

Japan: Measures of annual headline and core inflation, 2011-July 2016

Sources: Japan Statistics Bureau, Bank of Japan, and author adjustments in fiscal 2014 for VAT hike. The base year is 2015, with the exception of trimmed mean estimates prior to 2016 that use 2010 as the base year.

Indeed, we know of no instance in recent monetary history where a central bank has acted as aggressively to raise inflation—yet, with so few results—as the Bank of Japan since the 2013 change in leadership. Unlike his predecessors, Governor Kuroda has repeatedly committed to do “whatever it takes” to achieve the BoJ’s 2% inflation target. And, while observers are sometimes disappointed by the Policy Board’s decisions to hold steady at specific meetings, their resolve to end deflation is surely stronger than at any time since prices began falling more than a generation ago.

So, why has an aggressive policy yielded such meager results?

It is worth keeping in mind that aggressive monetary policies have worked even in periods when riskless interest rates were close to zero, private risk premia were elevated, banks were fragile, and burdensome debt overhangs were pervasive. The case of the Great Depression in the United States comes immediately to mind. Between July 1929 and March 1933, U.S. consumer prices and industrial production, plunged by 27% and 52% respectively. Then, conditions turned on a dime so that, by the end of 1935, prices had rebounded by 10% and production by 75% (see chart).

United States: Consumer Prices and Industrial Production (July 1929=100), 1929-35

Note: Blue line marks March 1933. Source: FRED and authors’ conversion to July 1929=100.

What triggered this sudden reversal of fortune in 1933? In our view, it was the stunning shift in the U.S. monetary and prudential regime that included the combination of abandoning the Gold Standard and buttressing the fragile banking system. These changes—the Depression era version of “whatever it takes”—sharply altered expectations virtually overnight, changing the behavior of households, firms and banks in short order.

So, why, as Japanese monetary policymakers keep pushing out the frontiers of the possible, is there still a problem? This profound puzzle is leading many people to ask about the role of fiscal policy. We share the commonly-held view that policy stimulus in the advanced economies ought to include a substantial expansionary fiscal component that has generally been lacking.

This is definitely not the path the current Japanese government has followed. Since taking office at the end of 2012, Prime Minister Abe has overseen a large fiscal tightening: current IMF estimates show Japan’s structural fiscal deficit shrinking by 3.7% of potential GDP over the past three years. Most of this tightening reflects the April 2014 hike of the consumption tax, the first such increase in 17 years. The impact appears to have been quite large. Indeed, Cashin and Unayama estimate that, upon announcement of Abe’s tax plans in October 2013, households reduced consumption by 5.2%. This enormous downshift apparently anticipated not only the 2014 consumption tax hike of 3%, but the plans for an additional 2% hike that was scheduled for October 2015, but has been delayed at least until 2019.

We are left with a rather conventional explanation of Japan’s experience: stimulative monetary policy is battling contractionary fiscal policy. Indeed, in light of Japan’s high sovereign debt, still-large deficits, and the rising social costs of an aging population, the IMF—in its August 2016 Article IV Consultation—calls for further consumption tax hikes of “0.5-1 percentage points over regular intervals until the rate reaches at least 15 percent.” Just imagine the impact if households were to anticipate that future consumption tax path all at once! Of course, it may be that this prospective tax framework is already depressing activity and prices: policymakers and academics have been warning for many years that restoring debt sustainability will require a large fiscal tightening (see, for example, Hoshi and Ito (2012)).

In his recent luncheon address at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City’s annual Jackson Symposium, 2011 Nobel Prize winner Christopher Sims went beyond this conventional perspective, arguing that monetary expansion will not succeed in driving up inflation if “low interest rates fail to generate substantial fiscal expansion.” According to this fiscal theory of the price level (FTPL), at low interest rates, stabilizing inflation requires a modicum of fiscal-monetary cooperation: the fiscal policymaker must be seen as willing to run an easier future policy that is consistent with higher inflation. Put differently, today’s price level is jointly determined by monetary and fiscal policy. And, it is not just today’s policies that matters, but the entire path into the distant future (see Leeper for a primer and topical examples, and Cochrane for a broad update).

In Sims’ words: “If in the face of low inflation the central bank lowers interest rates, demand increases and inflation rises only if the reduced interest expense component of the budget is expected eventually to flow through to a reduced primary surplus.… There is no automatic stabilizing mechanism to bring the economy back to target inflation and stay there, unless the commitment to true fiscal expansion at very low interest rates is widely understood.”

The symmetrical view—that, in a world of rapidly rising sovereign debt, the fiscal authority must be seen as committed to future primary surpluses to keep the debt sustainable and prevent or contain a large inflation—is supported both in theory (Sargent and Wallace) and practice. Sargent, for example, marshals evidence that hyperinflations end abruptly following changes in fiscal policy that restore a stable debt path. Absent such regime shifts, even relatively independent central banks are liable to be overwhelmed by episodes of fiscal dominance.

But, does the FTPL fit the facts of the sudden U.S. price turnabout in 1933? Economic historians argue that fiscal policy played only a secondary role in lifting the U.S. economy during the 1930s (see, for example, DeLong and Romer). Importantly, this assessment is not because fiscal policy doesn’t matter, but because discretionary fiscal stimulus was so limited and desultory until World War II. Eggertsson contends that fiscal expansion in 1933 gave credibility to the stated objective of raising prices. But, as was the case in 1937 with the first round of Social Security contributions. at times, fiscal policy turned quite contractionary.

Does the FTPL fit the facts for Japan? Well, as we indicated already, Japanese households do appear to anticipate a sustained period of rising taxes, presumably designed to cap the persistent rise of the nation’s sovereign debt ratio (see chart). That makes the BoJ’s job of hitting a 2% inflation target significantly tougher. However, the sustained increase in Japan’s net sovereign debt from 19% of GDP in 1994 to 129% in 2012 occurred precisely during the period of low interest rates and falling prices. Evidently, the large average structural deficit of 5.7% of potential GDP was insufficient to halt the deflation.

Japan: General Government Debt (Percent of GDP), 1990-2016

Source: IMF WEO database. Figures for 2015 and 2016 are IMF projections.

So, what to conclude? One need not accept the fiscal theory of the price level to believe that coordination of monetary and fiscal policy is in order when interest rates and inflation are as low as they are in advanced economies today. From this perspective, Sims’ prescription for Japan seems quite reasonable: link “future increases in the consumption tax to hitting and maintaining the inflation target.”