A Monetary Policy Framework for the Next Recession

“It is only a matter of time before another cyclical downturn calls for aggressive negative nominal interest rate policy actions.” Marvin Goodfriend, 2016.

Hope for the best, but prepare for the worst. That could be the motto of any risk manager. In the case of a central banker, the job of ensuring low, stable inflation and high, stable growth requires constant contingency planning.

With the global economy humming along, monetary policymakers are on track to normalize policy. While that process is hardly free of risk, their bigger test will be how to address the next cyclical downturn whenever it arrives. Will policymakers have the tools needed to stabilize prices and ensure steady expansion? Because the equilibrium level of interest rates is substantially lower, the scope for conventional interest rate cuts is smaller. As a result, the challenge is bigger than it was in the past.

This post describes the problem and highlights a number of possible solutions.

We start with a bit of data. The following two charts show key features of U.S. business cycles over the past 70 years. The first chart is about recessions: the rise in the unemployment rate is on the horizontal axis, while the cumulative size of the Fed’s rate cuts are on the vertical axis. For example, during the 1973-75 recession, the unemployment rate rose by 4.4 percentage points while the federal funds rate fell by 7.7 percentage points. The medians in this (admittedly small) sample are 2.6 percentage points for the unemployment rate and 5.1 percentage points for the policy rate. (This ratio is consistent with a modified Taylor rule where the coefficient on the unemployment gap is two, as described here.)

Peak to Trough Changes in the Unemployment Rate and the Federal Funds Rate Target, 1954-2009

Source: FRED, NBER and authors’ calculations.

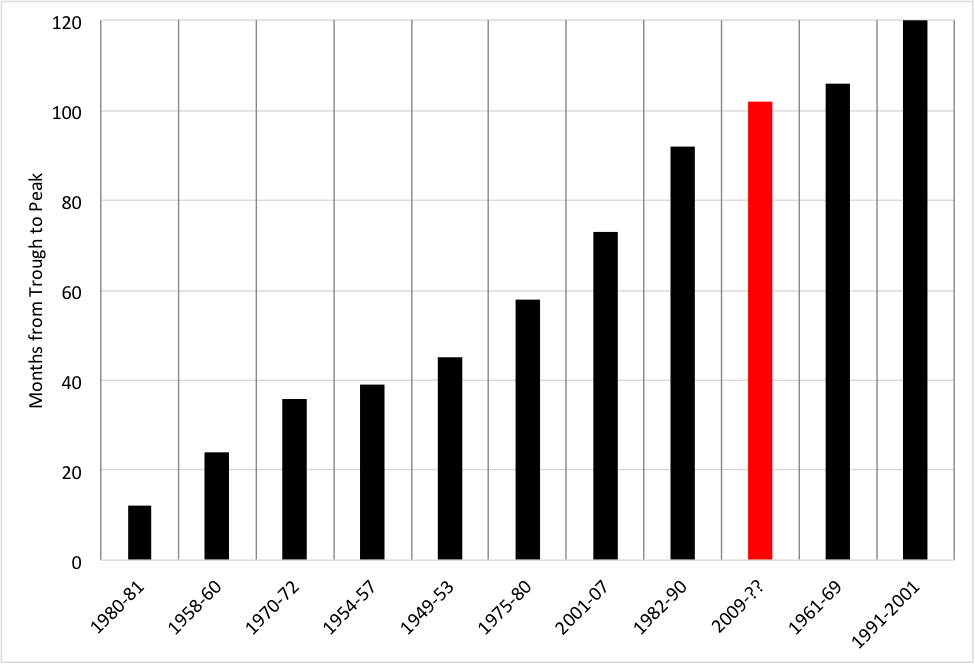

The second chart shows the duration in months of U.S. cyclical upturns. The current expansion, which is 102 months old, is in red. If it lasts into mid-2019, the current expansion will be the longest on record, eclipsing the 10-year upturn of the 1990s.

Duration of Post-WWII U.S. Expansions (Months)

Source: NBER.

This very simple compilation of the data leads us to two conclusions. First, monetary easing in recessions is typically equivalent to a 500-basis-point cut in the policy rate. Second, because upturns do not die of old age, the current boom may still have some room to run. Nevertheless, it is prudent to prepare for the next downturn, even if that is still a few years away. Because interest rates are very unlikely to rise to the pre-crisis level―the median forecast of FOMC participants for the policy rate in the longer-run (beyond 2020) is only 2.8%―the scope for conventional monetary policy in the next cycle is likely to be well short of what was possible in the past.

Now, this problem—not being able to lower interest rates sufficiently to counteract a typical recession—is a consequence of the fall in the neutral nominal interest rate. Part of this decline reflects policymakers’ success in lowering inflation: in the 1970s and 1980s, with inflation often well above 5 percent, the federal funds rate never came remotely close to zero. But, inflation has now been anchored close to 2 percent for nearly two decades. And, over the past decade, estimates of the neutral real interest rate have dropped sharply. With the median FOMC estimate now implicitly below 1 percent (after adjusting for the 2-percent inflation target), the likelihood of the policy rate hitting the zero lower bound (ZLB) in the next downturn has risen sharply. Earlier this year, Federal Reserve Board economists Michael E. Kiley and John M. Roberts estimated that the U.S. policy rate could hit zero more than one-third of the time.

Fully aware of the challenge, current and former central bankers, as well as academics, are re-examining the monetary policy framework. Do we need to move away from the inflation-targeting regime that has been so successful over the past quarter century? And, if so, what are the right changes?

In an earlier post, we summarized arguments for and against one obvious option: raising the inflation target. A higher inflation target means a higher neutral nominal interest rate, and provides more room for cutting the policy rate in bad times. Our conclusion then was that the case for shifting from a 2% to a 3% target was getting stronger, but was not yet compelling. Recent statements by current and former Federal Reserve officials suggest that raising the inflation target also is not the Fed’s first choice. (See Chair Yellen’s comments, Governor Brainard’s remarks, President Williams’ speech, and former-Chairman Bernanke’s detailed discussion.)

So, what other options are experts entertaining? We see three possibilities; two entail converting unconventional tools into conventional ones, and the third involves modifications to the inflation-targeting framework. Specifically, these are (1) further reliance on quantitative balance sheet policies, (2) implementing structural changes that make negative nominal interest rates more feasible, and (3) a shift to some form of price-level targeting.

Starting with the first of these, there is now broad (if not universal) agreement that balance sheet expansion has a stimulative impact. Based on a survey by Gagnon, Bernanke estimates that an increase in the balance sheet equal to 5 percent of GDP yields the equivalent of a 100-basis-point cut in the federal funds rate. To put this number into perspective, following a 500-basis-point cut in the federal funds rate target that started in mid-2006, the FOMC then increased the Fed’s balance sheet by $3½ trillion, which is a bit over 20 percent of GDP. That is, using Bernanke’s calibration, the Fed was able to ease by something like 900 basis points to combat the financial crisis and resulting recession. This leaves out any additional stimulus arising from the impact on financial conditions of forward guidance or of changes in the mix of Fed assets.

Assuming that the next recession is like those we have seen over the past 70 years (excluding the recent crisis), that the federal funds rate is roughly 2.8 percent when it starts, and that nominal GDP is around $21 trillion, the Fed would need to engage in more than $2 trillion in quantitative easing. While that is no longer unprecedented, it would almost certainly prove politically controversial, and could very well threaten the Fed’s independence.

Consider, for example, the concerns of Professor Marvin Goodfriend, an accomplished monetary economist with a deep knowledge of central banking whom President Trump recently nominated to the Federal Reserve Board. Last year, Goodfriend wrote critically of quantitative easing: “The effectiveness of more balance sheet stimulus is questionable…. Central banks will be tempted to rely even more heavily on balance sheet policy in lieu of interest rate policy, in effect exerting stimulus by fiscal policy means via distortionary credit allocation, the assumption of credit risk and maturity transformation, all taking risks on behalf of taxpayers and all moving central banks ever closer to destructive inflationary finance.”

This brings us to mechanisms for reducing the effective lower bound (ELB) on nominal interest rates. As it stands, the ELB is lower than zero only to the extent that the use of cash, which pays a zero rate, involves transactions costs (such as security, storage, transport, and insurance; see here and here).

Why use negative nominal rates as the principal policy tool? Arguably, interest rate policy has a more direct and predictable impact on inflation and growth, with fewer undesirable fiscal consequences. But—and this is a big but—lowering the ELB to increase the scope for lowering rates would require profound changes in the financial system.

As an advocate of using substantially negative interest rates, Goodfriend describes three approaches to accomplishing this task:

- abolish paper currency,

- introduce a market-determined flexible price of paper currency (measured in terms of a deposit or reserve dollar),

- and provide electronic currency (to pay or charge interest) at par with deposits.

Eliminating paper currency would surely prompt popular resistance. In a recent post, we discuss the possibility of halting issuance of notes larger than $20. But, getting rid of all cash would sacrifice its very useful service as a means of exchange and potentially weaken our freedoms by giving up anonymity as well. Absent greater financial inclusion, it also would particularly disadvantage the unbanked and underbanked, who lack effective substitutes to cash transactions.

Goodfriend’s second option is the most complex. In the current system, the Fed supplies paper currency perfectly elastically in exchange for reserves. For example, if an individual wants cash, she can withdraw funds from her account, triggering an analogous transaction between the commercial bank and the central bank. Both transactions are at par—that is, one dollar’s worth of the customer’s bank account or of the commercial bank’s reserves is exchanged for a single one-dollar bill. The deposit or reserve price of the dollar bill is fixed by the central bank’s elastic supply (much as a central bank can fix an exchange rate by purchasing or selling foreign reserves elastically).

In Goodfriend’s scheme, limiting the quantity of paper currency would alter the exchange rate between bank account dollars and physical paper dollars. When the central bank then lowers the interest rate that it pays on reserves below zero, scarcity would drive the price of paper cash (in terms of bank deposits or reserves) higher until the expected return on cash (adjusted for transactions costs) matched the negative return on reserves. Banks would then be able to lower rates on customer deposits below zero, too.

In theory, this proposal is logically sound. Once again, however, customers may resist the complexity of a floating-value dollar bill. In addition, making cash sufficiently scarce to cause its price to rise or fall could add to discontent. Absent overwhelming political support, we don’t see how a central bank could implement this approach. While there may be some jurisdictions where this is politically feasible today, we doubt that the United States is one of them.

Goodfriend’s final proposal for eliminating the ELB is for the central bank to replace paper currency with a form a digital currency that would be stored on debit cards linked to accounts at the central bank. These accounts would pay positive or negative nominal interest rates. In our view, central bank digital currency eventually would lead to an unappealing substitution of central bank intermediation for private intermediation (see our discussion here). In effect, the thing we call money—which today is mostly the liabilities of private banks—would become mostly the liability of the central bank. Over time, we suspect political pressures would compel the central bank to become a primary source of funds to the nonfinancial sector—a lender of first resort—taking over much of the intermediation activity currently done by commercial banks.

This brings us to the final proposal aimed at the problem posed by the ELB: shifting to price-level targeting. Instead of lowering the ELB in order to lower the nominal interest rate substantially below zero, this approach aims at temporarily raising inflation expectations to lower the expected real interest rate at the current ELB, thereby stimulating the economy.

A price-level target differs from today’s widespread form of inflation targeting in that past errors alter future policy: bygones are not bygones. That is, when prices deviate from the target path, monetary policymakers would be committed to make up the difference. For example, if the target is an annual price increase of 2% but inflation is only 1% in a given year, there will be a 1% shortfall relative to the price-level target. Over the policy horizon, the central bank will try to return to the intended price-level path. That might be achieved by delivering 3% inflation the next year, before returning to 2% inflation the year after that. In its pure form, a price-level targeting system is symmetric: if inflation is above target, then policymakers will work to engineer a period of low inflation to bring the price level back to its target path. Put differently, policy rates respond to the price-level gap—the deviation of the level of prices from a steadily increasing path—not to the inflation gap.

A credible commitment to price-level targeting solves the ELB problem by lowering the expected real interest rate without lowering the ELB for the nominal interest rate. To see how, consider a case where the economy has slowed, lowering prices well below the target path. With price-level targeting, people will anticipate a period of higher inflation to return to the target price path: this lowers the real interest rate below what steady inflation targeting could achieve.

In an earlier post, we discussed how the Bank of Japan has adopted a policy framework that is akin to price-level targeting in an effort to raise inflation expectations, lower real interest rates and spur faster growth. While there appears to be modest progress, it remains far from clear that a central bank that has tolerated deflation for a generation can quickly raise inflation expectations through a complex and nuanced alteration in its policy framework. As it is, core inflation in Japan still appears well below 1 percent.

Price-level targeting also can lead a central bank to amplify, rather than counteract, some disturbances. Consider, for example, a sharp negative supply shock that prompts a temporary spike of inflation and lowers output. In an inflation-targeting framework, the central bank will react sufficiently to maintain its inflation objective. Under price-level targeting, the central bank may be compelled to pursue a deflation to restore prices to their targeted path within the policy horizon. Given the asymmetry of central bank tools (it is easier to raise interest rates than to lower them below the ELB), pursuing a deflation (however temporary) seems risky.

To avoid such risks, Bernanke proposes a shift to an asymmetric framework of temporary price-level targeting in a recession. The idea is that policymakers will normally target inflation, implementing the alternative only when the policy rate approaches the ELB. So, the central bank would target inflation in the face of an inflation spike, but turn to price-level targeting when a large shortfall of aggregate demand depresses inflation sufficiently below target.

Once again, as in the Japan example, we suspect that such a complex framework, while logically consistent, would be difficult for many people to understand, with the result that its impact on inflation expectations would be relatively modest, at least in the short run. In addition, as Governor Brainard says, it may be difficult calibrate such a policy. Overshooting would risk a return to stop-go policies, a loss of policy credibility, or both.

So, where does this leave us? First, as appealing as it may be on theoretical grounds, we still do not see deeply negative nominal interest rates as a plausible countercyclical tool when the next recession inevitably arrives. That is, making the structural changes to the U.S. monetary and financial system to accommodate the possibility of lowering interest rates to –2% or lower looks impractical, at least over the medium term. Second, we welcome discussions focused on the appropriate monetary policy framework, but are skeptical about a quick shift to price-level targeting: it took nearly 20 years from the time that the FOMC began discussing inflation targeting to its adoption in 2012. From our perspective, widespread political buy-in that secures central bank independence would be needed for such a major shift.

This leaves us with balance sheet policy. Like it or not, we expect the Fed to alter the scale and mix of its balance sheet extensively again in the next downturn. As Federal Reserve Bank of Boston President Eric Rosengren said earlier this year: “[B]alance-sheet expansions—and exits—are likely to become more standard monetary policy tools around the world."