TARGET2 Balances Mask Reduced Financial Fragmentation in the Euro Area

As we write, the claims of the Bundesbank on the other euro-area national central banks (NCB) through the TARGET2 system are approaching €1 trillion. What do these claims represent? Are they subsidized German loans to other euro-area countries―primarily Italy, Portugal and Spain? Do they signal further financial disintegration in Europe? Or, as large as these numbers are, are they simply a consequence of the complex mechanics related to the construction of the Eurosystem and how it implements monetary operations?

The answer is two-fold: for the first few years of the euro-area crisis―when German claims peaked at €750 billion―imbalances reflected subsidized loans to counter rising financial fragmentation. From 2008 to 2012, funds shifted from banking systems in the periphery of Europe perceived to be under stress, to banks in the core seen as being relatively stable, creating a web of liabilities and claims among NCBs. After 2012, the risk of breakup receded, so the interpretation of renewed increases in TARGET2 balances has changed. Indeed, the doubling since early 2015 is a natural (and almost inevitable) consequence of the manner in which the Eurosystem implements its various asset purchase programs (APPs)―their version of quantitative easing and large-scale asset purchases. Moreover, the impact of the APP expansion on TARGET2 balances has concealed a further, if still incomplete, reversal of the financial fragmentation triggered by the euro-area crisis several years ago.

To be sure, the increase of TARGET2 balances in both periods reflects a credit expansion, but in the latter, the NCBs collectively earn a return that is far more market sensitive. Put differently, the increase of TARGET2 liabilities associated with the Eurosystem’s APPs is backed by marketable assets that could, and probably should, be transferred to the national central banks (NCB) that currently have claims on the system. While such a transfer would increase their exposure to fluctuations in the value of euro-area sovereign debt, it would reduce any losses that would accrue in the extreme event of a euro-area breakup. Presumably, governments and NCBs should care more about the latter.

Before explaining the mechanics of TARGET2, and our suggestion for rebalancing among the NCBs, we start with data on the evolution of TARGET2 balances. The following chart shows claims in green and liabilities in brown. For at least a decade, with only a few exceptions, countries tend to stay on one side or the other. Three countries have persistently large claims: Germany, Luxembourg and the Netherlands. By contrast, Greece, Italy, Spain, and Portugal have sizable liabilities. (Ireland’s liabilities peaked at nearly €150 billion at the height of the crisis, but have since disappeared.) For reasons that we will make clear, the ECB itself now has liabilities of nearly €250 billion―roughly two-thirds of the “Other Liabilities” in the chart.

TARGET 2 Liabilities and Claims (Billions of Euros), Jan 2006-May 2018

Source: European Central Bank.

To explain these developments, we first need to provide a few details on the functioning of the euro-area cross-border payments system. Consider an apparently simple transaction: a Spanish tourist who lives in Madrid travels to the Netherlands and has a €100 meal in Amsterdam. Now, if the tourist had been at home, going to a restaurant in Madrid, the transaction would have cleared in the following straightforward way: (1) the buyer’s bank would debit their customer’s account; (2) the Bank of Spain (the Spanish central bank) would transfer funds from the reserve account of the buyer’s bank to that of the restaurant’s bank; (3) the restaurant’s bank would credit their customer’s account. That is, everything would have stayed inside the Spanish banking system and been facilitated by the Bank of Spain.

But, with the tourist in Amsterdam and the seller having a Dutch bank, the transaction is more complicated. Because the Eurosystem simply combines the banking systems of the member states, the two commercial banks―the one in Spain and the one in the Netherlands―are not connected directly through a single NCB. Instead, the tourist’s Spanish bank has a reserve account at the Bank of Spain and the Amsterdam restaurant owner’s Dutch bank has one at the Netherlands Bank. To settle this transaction, there is an additional cross-border operation involving the European Central Bank (ECB).

The following balance sheets illustrate what happens. The top row shows the customer transactions on the balance sheet of the two commercial banks: a €100 payment from the Spanish tourist to the Dutch restaurateur. Next, are the two banks transactions at their respective NCBs: a decrease in the reserve account at the Bank of Spain and an increase in the one at the Netherlands Bank. This transaction uses the TARGET2 payments system and creates both an asset for the Netherlands Bank and a liability for the Bank of Spain. The final row shows the impact of these TARGET2 changes on the balance sheet of the ECB.

As is well known, when the financial system in one or more euro-area member states comes under stress, this mechanism leads to rising TARGET2 imbalances. To understand why, suppose that people lose confidence in the Spanish banking system and start to flee. When a depositor shifts funds from a commercial bank in Spain to one in the Netherlands, the transaction is analogous to the one above, just with the Dutch bank account belonging to the Spaniard (or their agent). As with the restaurant transaction, deposit flight from Spain leaves the Bank of Spain with a TARGET2 liability and the Netherlands Bank with a TARGET2 claim. (See Peter Garber’s prescient 1998 paper, as well as the more recent discussions in Cecchetti, McCauley and McGuire and Sinn and Wollmershäuser.)

From mid-2011 to mid-2012, the TARGET2 liabilities of the Bank of Spain and the Bank of Italy alone rose by a combined €682 billion. With the implementation of the ECB’s Outright Monetary Transactions program following ECB President Draghi’s famous promise to do “whatever it takes,” financial systems in the euro-area periphery stabilized. As a result, by end-2014, TARGET2 balances had receded from a cumulative peak of €1.1 trillion to just over €600 billion. Then, however, balances began to rise again. Looking at the first chart above, we see that over the past 4 years, claims and liabilities more than doubled. As of end-May 2018—the latest available reading—the imbalance stands at €1.39 trillion.

However, the post-2014 TARGET2 increases do not reflect renewed bank runs: instead, they are a virtually direct consequence of the ECB’s APPs. Most central banks began their quantitative easing programs almost immediately following the September 2008 Lehman bankruptcy. While the Eurosystem did allow its balance sheet to increase, it was not until March 2015 that the Governing Council of the ECB authorized significant outright purchases of bonds. These APPs involved covered bonds, asset-backed securities, corporate bonds, and public-sector bonds. As of end-June 2018, the ECB has accumulated a combined total of €2.45 trillion of these instruments. The proportions of the sovereign holdings match the central bank’s capital key, limiting the risk of fiscal dominance in the most heavily indebted states.

We will focus on the public-sector purchase program (PSPP), which accounts for 80% of ECB APPs. In addition to government bonds, the PSPP also includes supranational bonds issued by international organizations and by multilateral development banks located in the euro area. Central banks purchase the sovereigns issued by their own government, as well as some of the supranationals, with the latter accounting for 12% of the total. Furthermore, the ECB purchases 8% of the total directly―currently around €163 billion. (As ECB President Draghi noted when he announced the PSPP, and we discuss in an earlier post, the implication of this is that 20% of the purchases are subject to a regime of risk sharing.)

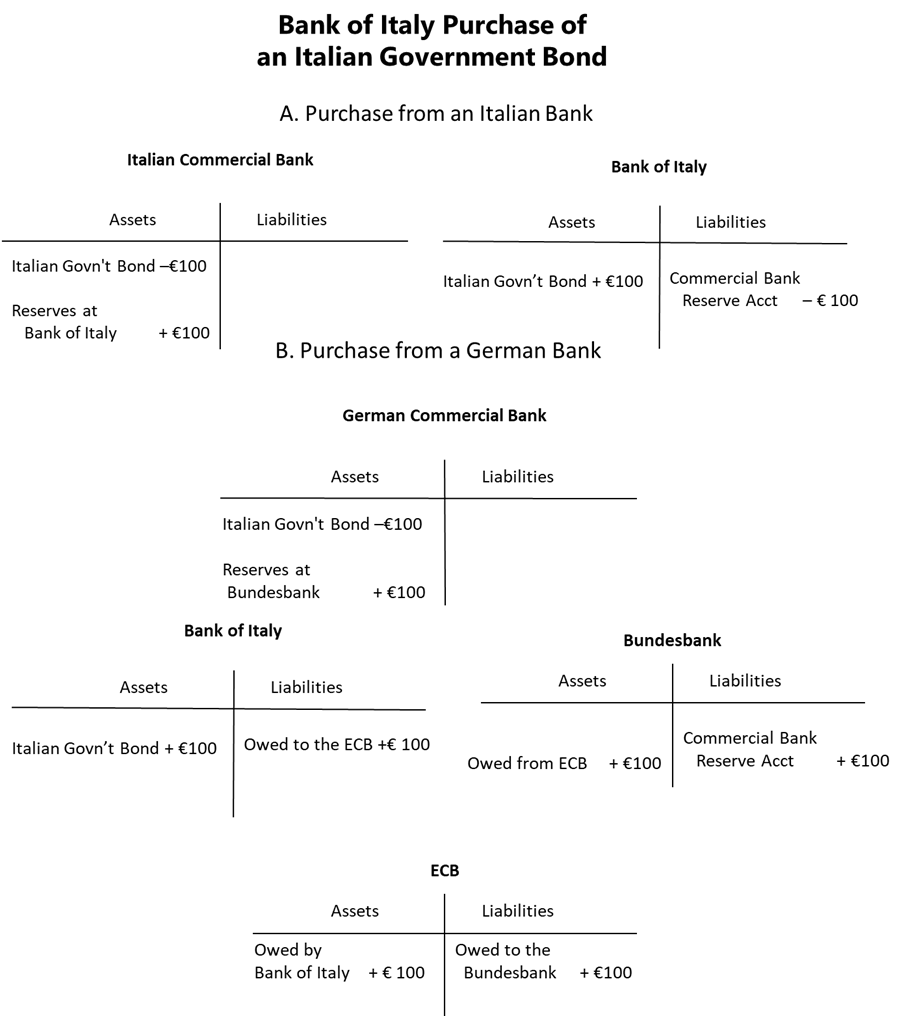

To see how NCB bond purchases alter TARGET2 balances, consider the case where the Bank of Italy acquires an Italian government bond. If the purchase is directly from an Italian bank, then this is a straightforward open-market operation: the Bank of Italy credits the reserve account of the bank, as shown in panel A below, and that is the end of the story. There is no impact on TARGET2.

Panel B shows what happens if the Bank of Italy purchases the same bond from someone outside of Italy. For simplicity, suppose the purchase is from a German bank with a reserve account at the Bundesbank. Then, the German commercial bank’s reserve account at the Bundesbank increases, as does the Bank of Italy’s government bond holdings. But, that can’t be the end of the story. Balance sheets have to balance. As was the case with the Madrid tourist dining in Amsterdam, there are offsetting transactions in the TARGET2 system: the Bank of Italy incurs a liability and the Bundesbank has a claim.

As Eisenschmidt et al. note, this is the typical case: “around 80% of APP purchases by volume have been from non-domestic counterparties (i.e. counterparties located in a jurisdiction other than that of the purchasing central bank, including other euro area countries).” In their September 2017 ECB occasional paper, these same authors go on to conclude that “large and persistent TARGET balances do not necessarily reflect stress-related developments.” (Gros provides a similar, detailed analysis of the TARGET2 developments and their implications.)

Returning to the case of the ECB itself, as we noted earlier, the ECB has a TARGET2 liability of nearly €250 billion. We can now see that this arises from the ECB’s direct purchase of bonds. To understand the mechanism, consider a case where the seller is a French commercial bank with an account at the Banque de France. The result of this purchase is (1) a credit to the French reserve account at the Banque de France, (2) a TARGET2 claim of the Banque de France, (3) a bond asset on the balance sheet of the ECB, and (4) a TARGET2 liability of the ECB. (Looking at the disaggregated balance sheet of the Eurosystem, we can see that the ECB’s direct holdings of securities differ from its TARGET2 liability by roughly €2 billion.)

We draw two important lessons from this analysis. First, the increases in TARGET2 balance since the onset of the APP in March 2015 are almost surely the consequence of the mechanics of the program’s implementation. In fact, using the ECB authors’ 80% fraction, the total balance would be €1.95 trillion―€560 billion higher than it is today! Put differently, after adjusting for the large influence of the APP programs, the fragmentation that resulted from the crisis-related runs has continued to reverse in recent years. Second, we can think of the assets purchased through the APP programs as collateral for the TARGET2 liabilities. That is, it would be possible to reduce TARGET2 balances by transferring securities obtained as a part of the APP from central banks with TARGET2 liabilities to those with claims.

The fact that there are specific assets backing today’s TARGET2 liabilities makes them very different from those prior to the 2015 advent of the Eurosystem’s asset purchase programs. In June 2012, when Eurosystem assets peaked at €3.1 trillion, most were in the form of repurchase agreements arising from the various commercial bank refinancing operations. That is, the NCBs were providing reserves to their banks through lending operations rather than outright purchases. Of course, there was collateral for these loans, but the quality of this collateral varied greatly (and could be of far inferior quality to the sovereign and supranational instruments included in the PSPP). As a result, the ECB and the NCBs combined held fewer than €300 billion in securities (listed as “for monetary policy purposes”); far less than the €1.1 trillion in TARGET2 claims.

Were euro-area members so inclined, the availability of specific sovereign securities to back TARGET2 balances provides a means to reduce them. The approach we have in mind mirrors the one employed in the United States, where the Federal Reserve System occasionally settles imbalances between the Federal Reserve Banks through an asset transfer. The Fed publishes the imbalances in its weekly financial statement on the line labelled “Interdistrict settlement account.” In recent years, these have often exceeded $100 billion for some districts. To limit the accumulation of imbalances, each April the Fed reallocates its securities portfolio, shifting assets from Reserve Banks with liabilities to those with claims. (For a detailed description of this process, and its relationship to the TARGET system, see Wollman.)

Could the Eurosystem adopt a similar practice, shifting securities from NCBs with liabilities to those with claims? As we noted earlier, prior to the APP, there were very few securities, so there would have been no simple way to implement such a reallocation. Today, the APP assets are roughly twice the level of TARGET2 balances. However, the distribution of securities among the NCBs with liabilities means that their reallocation could offset only part of the APP’s impact on TARGET2 imbalances. The following chart tells the story: the green bars represent securities holdings and the orange bars are TARGET2 claims and liabilities. (The “Other” category includes all of the jurisdictions with less than €100 billion in assets and less than €50 billion in TARGET2 claims or liabilities.) The diamonds (and numbers) sum the values in these two bars. That is, they show the size of each NCB’s securities portfolio following a complete rebalancing of the TARGET2 system: the Bundesbank would have €1,497 billion, the Banque de France €426 billion, and so on. The problem arises from those countries where diamonds (and numbers) are below zero: namely, Portugal (–€31 billion), Spain (–€68 billion) and Italy (–€99 billion). These shortfalls, which total €200 billion, indicate that these countries do not have sufficient securities (purchased as a part of the APP) to meet their full TARGET2 obligations.

TARGET2 Claims and Securities Holdings, end-May 2018

Note: The diamonds (and associated numbers) sum each NCB’s securities holdings and TARGET2 balances. A negative number means that the NCB’s TARGET2 liabilities exceed its securities holdings. A positive number is the level of securities that an NCB would hold following a complete rebalancing. Source: European Central Bank.

Before concluding, we expect that our European friends would question how they could accomplish the transfer of sovereign holdings given the incomplete risk-sharing arrangement mentioned earlier. That is, under the PSPP, NCBs are responsible for 80% of the risk in their holdings of sovereigns issued by their own government. So, if the Bank of Italy were to transfer its holdings of Italian government bonds to the Bundesbank, wouldn’t that shift the risk as well? We have two reactions to this. First, in the extreme event of an Italian exit from the Eurosystem, we suspect that the German government (through the Bundesbank) would prefer to own marketable bonds outright rather than TARGET2 claims on the Bank of Italy. Second, to limit the risk transfer, policymakers could make the bonds used to settle TARGET2 imbalances senior to comparable government bonds.

All of this leads us to several conclusions. First, we should only interpret those changes in TARGET2 balances that are not associated with asset purchases as a symptom of financial stress. So, for example, from the beginning of March (prior to the Italian election) to the end of May (following the formation of the current government), the Bank of Italy’s liabilities rose by €22.2 billion while securities holdings increased by €9.7 billion. Only the gap between these two figures could reflect deposit shifts that, as we noted at the time, might result from perceptions of heightened risks of an Italian exit from the euro.

Second, we should interpret the bulk of today’s TARGET2 balances as an artifact of the way in which the Eurosystem implements its APPs. The total current liabilities of €1.385 trillion are extremely misleading. Creditor countries may find it advantageous to view the vast majority as claims by one NCB on securities that happen to sit on the balance sheet of another NCB (or on the ECB’s own balance sheet). In support of this perspective, the Eurosystem should follow the lead of the Federal Reserve and rebalance the system annually. While the distribution of securities holdings currently limits that asset transfer, the maximum feasible reallocation would still slash TARGET2 imbalances by more than €1.1 trillion, or nearly 85%. This transfer would make clear the extent to which financial fragmentation has receded since its peak in 2012.

Third, the analysis of TARGET2 balances reinforces our view of the importance of completing the banking union. When all euro-area banks have the same backing, when they have common deposit insurance, and when they hold a European safe asset rather than individual sovereign issues, then there will be no runs from one member state to another because national banking systems will no longer exist. And, to the extent that TARGET2 balances happen to arise, NCBs will be able to shift some form of safe sovereign debt (such as ESBies) among themselves to settle the accounts.

Acknowledgment: We thank our friend and colleague, Daniel Gros, for helping us to understand some of the intricacies of the Eurosystem’s balance sheet.