Some Unpleasant Gold Bug Arithmetic

Most people care far more about the prices of things they purchase—food, housing, health care, and the like—than the price of gold. Not coincidentally, professional economists display a remarkably explicit consensus against forcing the central bank to adopt a policy that fixes the price of gold.

Yet, there are still powerful people who think that the United States would benefit if the central bank’s sole purpose were to restore a gold standard. Senators Rand Paul and Ted Cruz are supporters, as is West Virginia Representative Alexander Rooney, who recently proposed legislation to “define the dollar as a fixed weight of gold.”

With the nomination of gold standard advocate Judy Shelton to be a Governor of the Federal Reserve, we feel compelled to take these views seriously. So, here goes.

Several years ago, we emphasized that a gold standard is incredibly unstable:

It limits the most powerful tools the central bank has for halting bank panics: the authority to act as a lender of last resort.

Unless the central bank holds gold stocks sufficient equal or greater in value than its liabilities, the system invites speculative attack—especially during recessions and when the financial system is under stress.

Historically, the dollar prices of the goods and services people consume tend to vary more under a gold standard than under a fiat money standard with a flexible exchange rate.

If the United States goes it alone, the real exchange rate value of the dollar will become much more volatile. Changes in gold supply and demand will alter the gold price of other currencies, but not the dollar.

As historians have emphasized, the gold standard helped spread the Great Depression from the United States to the rest of the world (see Ben Bernanke’s 2012 lectures on Origins and Mission of the Federal Reserve.)

All these arguments are rather abstract, directed at how a gold standard would operate once it is in place. They ignore the mechanics of how the central bank would run the system. In our view, it is incumbent on any gold standard advocate to answer a series of practical questions: What gold price are they proposing? How much gold would the Federal Reserve have to acquire and hold to make the scheme credible? Will the Fed be able to lend to banks and operate as a lender of last resort?

In the remainder of this post, we consider these questions and provide straightforward answers. Since the Fed initially would commit to holding a particular dollar value (that is, the product of price and quantity) of gold, we need to consider price and quantity together. With the smallest balance sheet we can imagine, our best guess is that the Fed initially would have to triple its gold holdings, driving the price of gold up by two thirds (to about $2,600 per ounce). Then, to maintain the gold standard, the Fed would still need to purchase one-third of world gold production each year. Without gold holdings over and above this minimum, the Fed would not be able to lend at all, much less without limit as it can under a pure fiat money standard.

Turning to the details, a gold standard fixes the currency value of a specific quantity of gold. The Gold Standard Act of 1900 set the value of one U.S. dollar at 1.5046 grams of pure gold—the equivalent of $20.67 per troy ounce. In 1934, President Roosevelt increased the price to $35 per ounce, where it stayed until 1971, when Richard Nixon ended the convertibility of the U.S. dollar into gold. Since then, markets have determined the price, which peaked at nearly $1,900 in September 2011. More recently, the price has been between $1,500 and $1,600. (If we were to plot this in 2020 dollars, gold peaked in 1980 at $2,235.)

Price of gold (U.S. dollars per ounce)

Source: FRED (GOLDAMGBD228NLBM).

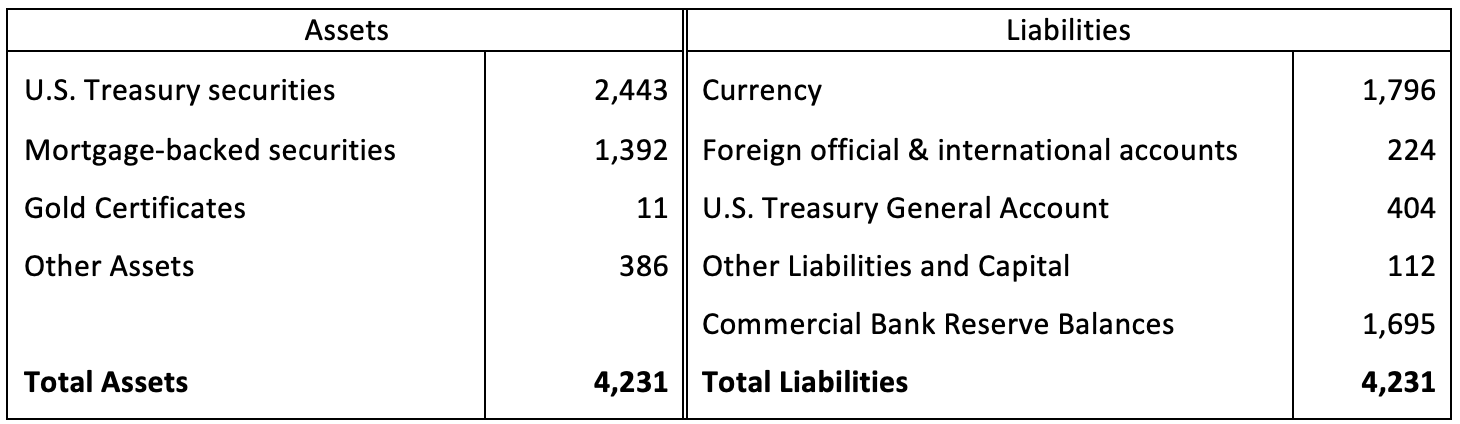

Turning to our first question: if the Federal Reserve were to reinstitute a gold standard, at what price would they do it and how much gold would the Fed have to buy? To get some sense of the value of the gold that the Fed would have to hold, we can start with their current balance sheet. The following table provides the latest snapshot of the Fed’s relevant assets and liabilities.

Consolidated balance sheet of the Federal Reserve System (Billions of dollars), February 12, 2020

Source: Federal Reserve H.4.1, February 12, 2020.

To limit the quantity of gold needed, imagine shrinking the Fed’s liabilities as much as possible, supporting what remains with gold. To do this, start by exchanging all reserve balances for U.S. Treasury securities. Next, assume the Treasury general account returns to its pre-crisis level of $5 billion, with the remaining $400 billion deposited in commercial banks and secured by Treasury securities. While it works against the desire to have the U.S. dollar remain the foundation of the global monetary system, the Fed could also kick out foreign official accountholders.

After shedding more than $2 trillion in liabilities, roughly $2 trillion would remain. To go significantly lower, one could cancel all $100 bills outstanding after a certain date. But since gold advocates likely would object, we rule that out. Instead, we assume that gold holdings will need to accommodate the ongoing rise of currency in circulation: if the recent average annual increase of nearly $100 billion continues, currency would reach $2.6 trillion in 2030. (If, instead, we assumed a constant geometric growth rate, then currency would reach $3.5 trillion.)

Putting this all together, in very rough numbers, the Fed would have to accumulate sufficient gold to support a balance sheet of $2 trillion today, with subsequent growth of $100 billion per year.

How might this work? Well, to start, the Fed currently own $11 billion worth of “gold certificates.” Treating these as gold, they represent 8,100 metric tons—about 260 million ounces—at a statutory price of $42.222 per ounce.

Of course, there is a vast amount of gold in the world. The World Gold Council estimates current above-ground gold stocks at nearly 200,000 tons (6.8 billion ounces). Of this, half is in jewelry, private investors hold another 22%, and official sector holdings account for 17%. In addition, current production is 3,500 tons per year, with an additional 1,200 tons being recycled. Furthermore, jewelry and industrial demand is 2,500 tons per year—more than half of the amounts mined and recycled.

So, how would the Fed acquire the necessary gold? This brings us to the unpleasant arithmetic we refer to in the title of this post. To help understand the problem, consider the “gold-backing” identity:

Central Bank Liabilities = Price of Gold × Quantity of Gold × (Liabilities/Value of Gold)

That is, under a gold standard, central bank liabilities (currency plus reserves plus other liabilities) equals the quantity of gold times the price of gold times the inverse of the “gold backing ratio.” Importantly, all of these are under the control of the central bank, at least initially. That is, they can set the dollar price of gold. They can decide how much gold to hold at that price. And, they can fix a minimum backing ratio.

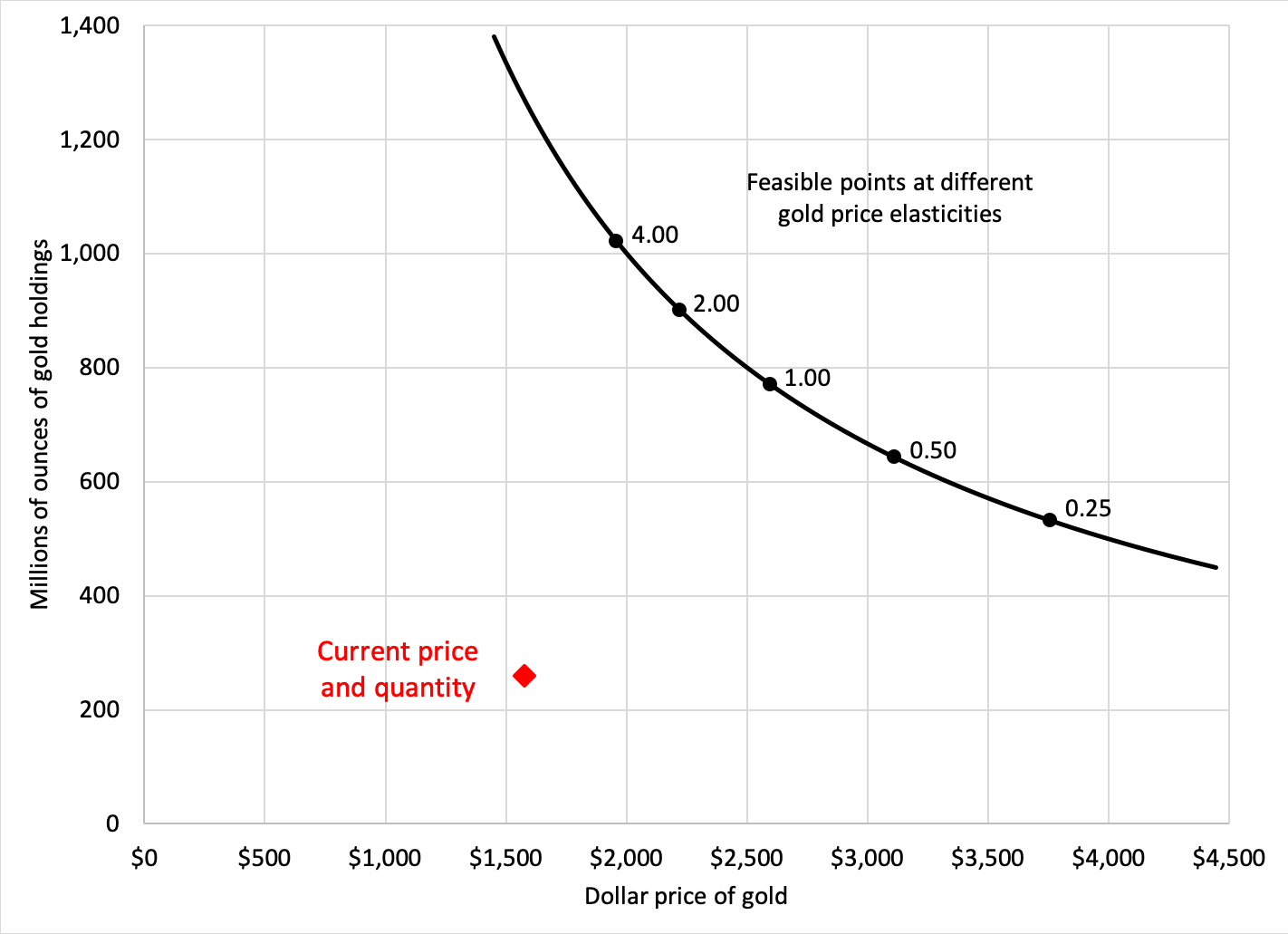

This identity has important implications. To understand what they are, start by assuming that the backing ratio is one (as was the case for the U.S. standard before 1933; see Bernanke’s 1994 JMCB Lecture). We see this as the benchmark. At any lower ratio, the central bank would likely become the victim of runs and speculative attacks (as with virtually any fixed-exchange rate regime in the absence of capital controls). Next, we construct a price-quantity frontier that corresponds to Fed liabilities of $2 trillion. This is the black line below. Anywhere along this line, the Fed would have sufficient gold to back a minimal balance sheet. The red diamond shows the current market price ($1,575 per ounce) and quantity (260 million ounces) on the Fed’s balance sheet. This is the starting point.

Gold volume-price combinations corresponding to a $2 trillion value of Federal Reserve gold holdings

Source: Federal Reserve H.4.1 and authors’ calculations. Our calculations are for the price elasticity with respect to official sector holdings.

With $2 trillion in liabilities, the Fed would have to increase its gold holdings sharply, moving from the red dot to the black line. This will surely drive up the price, with the scale of the increase dependent on the price elasticity of gold supply. If gold supply is very elastic (say, above 1), so that substantial quantities are forthcoming without big price movements, then the result could be a point that is relatively far to the left. At a very high elasticity of 4, the gold price would rise to around $1,950, and the Fed would need to purchase about 750 million ounces. At a somewhat more realistic elasticity of one, the gold price would rise to $2,600 (a 65% increase), and the Fed would triple its current holdings by purchasing 510 million ounces of gold. The central bank would then permanently fix the price of gold, standing ready to exchange its liabilities for gold. One could rename the Fed the “U.S. Gold Board.”

This is just the beginning. From then on, as demand for its liabilities increases. the Fed will have to purchase gold. Earlier we noted that the demand for currency is increasing at a rate of $100 billion per year. At a gold price of $2,600 per ounce, this means purchasing nearly 40 million ounces (1,200 tons) of gold per year every year. That represents about one-third of the annual mining output, so the upward pressure on the price of gold would make it difficult to achieve a stable gold price without limiting the supply of currency (and depressing economic activity).

Before continuing, we highlight three key points. First, in our computations, we are assuming that commercial banks hold virtually no reserves (down from $1.65 trillion today). To meet banks’ reserve demand, the Fed would need to purchase even more gold. Second, the status of private bank liabilities--the deposits that make up what we think of as money—remains as it is today. As in the past, this supply of money—which is key for supporting economic activity—need not be steady under a gold standard. Third, in this system, taxpayers will be paying dearly to dig gold out of the ground and put it into the Federal Reserve’s vault.

Turning to the last question: Will the Fed be able to lend to banks and operate as a lender of last resort? If the minimum backing requirement is one, the only way to have flexibility to lend is for the central bank to accumulate excess gold. To do this, the Fed could issue a special type of equity to the U.S. Treasury, agreeing to back it either by gold or by loans to commercial banks. But, the fiscal authorities would surely cap this facility, thereby constraining the central bank’s ability to lend during a bank panic. If the central bank cannot lend without limit, how would it stop a system-wide panic?

To conclude, in our view, anyone promoting the adoption of a gold standard should be required to answer three essential questions: 1) What would be the dollar price of gold under the new standard? 2) Would the Federal Reserve accumulate sufficient gold to back its entire balance sheet? 3) Who would act as the lender of last resort to stabilize the financial system?

As we said at the beginning, our answers are that the price of gold will need to rise substantially as the Fed doubles, triples or even quadruples its gold holdings. And, most importantly, the Fed will no longer be able to operate as a credible lender of last resort. This means that the Fed will no longer be able to serve its original purpose—to provide an elastic supply of the currency and stabilize the financial system.

To quote from one of the lectures Ben Bernanke gave when he was Chairman of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System: adopting the gold standard “means swearing that no matter how bad unemployment gets you are not going to do anything about it.” In light of past U.S. experience with the Gold Standard, who would believe that?