Patience vs FAIT: Which is key in the new FOMC strategy?

“This change implies that the Committee effectively will set monetary policy to […] not preemptively withdraw support based on a historically steeper Phillips curve that is not currently in evidence and inflation that is correspondingly much less likely to materialize.” Federal Reserve Governor Lael Brainard, “Bringing the Statement on Longer-run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy into Alignment with Longer-Run Changes in the Economy,” Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy at the Brookings Institution, September 1, 2020.

The Federal Open Market Committee’s (FOMC) policy strategy update incorporates two key changes. The first is a shift to flexible average inflation targeting (FAIT), while the second is a move to what we will call a patient shortfall strategy. FAIT represents a shift in the direction of price-level targeting in which the FOMC intends to make up for past inflation misses (see our previous post). As Governor Brainard explains in the opening quote, the strategy of increased patience, embedded in language that focuses on employment “shortfalls” rather than “deviations,” reflects reduced willingness to act preemptively against inflation when the unemployment rate (u) declines below estimates of its sustainable level (call it u*).

The Committee will need to explain what these two changes mean for the determinants of policy—what we think of as their reaction function. For example, FAIT implies that the FOMC’s short-term inflation objective will change over time—possibly even from meeting to meeting. For the policy to have its intended impact of shifting inflation expectations, we all need to know the Fed’s inflation target. Similarly, having downgraded the role of the labor market as a predictor of inflation, the central bank will need to explain how it aims to control inflation going forward. While patience is the broad message, pointing to a more backward-looking approach to control, it seems likely that attention will shift to other inflation predictors. But again, if this shift is to have the intended impact on expectations, it is important that the Fed be clear about how it is forecasting inflation.

In this post, we compare the practical importance of these two strategic shifts. Our conclusion is that, while neither appears very large on average, the patient shortfall strategy looks to be the more important of the two. Compared with FAIT, it is likely to have a substantially larger impact on policy rates, especially in the latter stages of cyclical expansions when unemployment rates tend to be low. Accordingly, over time, patience could prove more controversial than FAIT. For now, however, with the unemployment rate more than double the latest FOMC median projection of u* (see here), a test of that view is almost certainly years away. As a result, it is no wonder that financial markets expect interest rates to stay near zero for a long time even as the economy recovers.

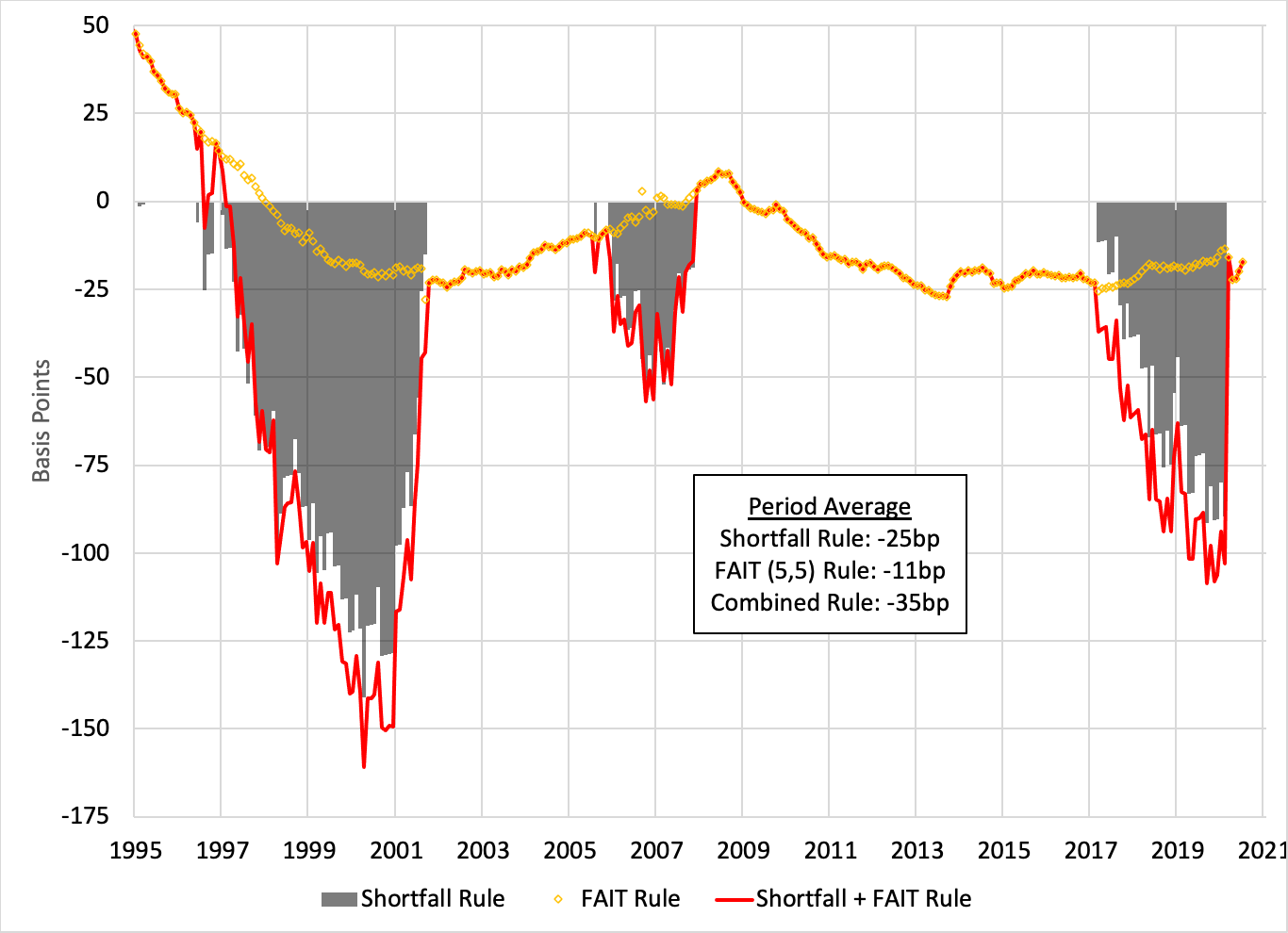

The following chart shows the results of our basic calculations. We take the observed inflation and unemployment readings over the past 25 years as given for each of three strategies: the patient shortfall rule, the FAIT rule and a combination of the two. In each case, the chart plots the deviations of the Fed policy rate from that of a simple Taylor rule that uses the unemployment rate gap (u minus u*) as the measure of resource utilization.

Deviations from a simple u*-based Taylor rule, 1995-Aug 2020

Notes: The FAIT rule uses the price index of personal consumption expenditures excluding food and energy. We use the CBO measure of the natural rate of unemployment for u*.

Sources: FRED and authors’ calculations.

Looking at the detail, the gray-shaded area shows the consequences of the shortfall rule. Specifically, this reflects the consequence of altering the Taylor rule by setting the impact of unemployment deviations to zero whenever the unemployment rate is below the natural rate of unemployment (u < u*). This patient shortfall strategy is explicitly asymmetrical: the policy rate is equivalent to the original Taylor rule level when u is above u*, otherwise it is lower by the gap between u and u*.

The FAIT rule (shown as the yellow diamonds) varies from the simple rule by altering the target inflation rate. Instead of a fixed 2 percent associated with standard inflation targeting, under FAIT the inflation target varies by the amount required to return average inflation to 2 percent over the targeting averaging period. For example, if FAIT implies a medium-term inflation target of 2.5% (rather than 2%), the rule subtracts 25 basis points from the simple policy rule, reflecting the coefficient of 0.5 on the inflation gap in the Taylor rule. Constructing a FAIT rule requires that we define both the historical look-back period and the target restoration time window: consistent with a 10-year average inflation targeting regime, we use 5 years for both windows. Shortening the restoration window would add to the variability of the implied medium-term inflation target, but the deviations from the simple rule would increase by only half as much.

Looking at the chart, we see that FAIT would have had a very modest impact on policy rates over the past 25 years. The average deviation is -11 basis points, with a standard deviation of 15 basis points. By contrast, the patient shortfall rule reduces the policy rate by 25 basis points on average, with a standard deviation of 38 basis points. As a benchmark for comparison, the average deviation since 1995 of the monthly effective federal funds rate from the simple Taylor rule is -25 basis points with a standard deviation of a whopping 177 basis points.

In our view, the most important message is the difference between the two rules. Despite the attention that FAIT is receiving, the patient shortfall rule has a bigger average impact. Moreover, its effect is far larger when u is below u*, reaching a minimum of -141 basis points (April 2000), compared to -28 basis points for FAIT (September 2001).

The citation from Governor Brainard makes clear why the FOMC adopted this patient shortfall rule. The FOMC no longer has confidence in the usefulness of a low unemployment rate for predicting inflation. We share this skepticism (see our primer on the Phillips curve). But the Committee still needs a model, if for no other reason to guard against the danger of significantly overshooting their long-run average objective. The inherently backward-looking nature of the patient shortfall rule raises this risk.

In practice, we expect that the Fed will incorporate a range of information into their forecasting process. Market measures of long-run inflation expectations are obvious candidates to include in the list, and the Fed might seek to identify a threshold for action. For example, since data became available in 2003, 10-year inflation expectations have exceeded 2.5% only about one-sixth of the time (see here). But, as has been noted before, the remarkable stability of long-term inflation expectations partly reflects the Fed’s price stability commitment, so it (too) may not serve well as a leading indicator.

Aside from inflation risks, another issue that could add to controversy is the impact of the patient shortfall rule on financial stability. The two large “shortfall” episodes of the past 25 years—1997-2001 and 2006-07—correspond to a stock market boom and a housing boom. Both subsequently gave way to damaging busts, with the latter triggering the Great Financial Crisis. John Taylor has blamed “monetary excesses” for the housing boom (see here). The timing and impact of a patient shortfall rule would add force to this argument.

While low interest rates are a potential source of financial stability risks, we see macro-prudential tools—especially capital and liquidity requirements—as the primary tools for preventing instability. At the same time, with financial safety losing political salience and authorities relaxing numerous measures intended to build resilience, advocates of monetary policy patience should be especially wary of threats to the financial system associated with persistent low interest rates.

The bottom line: we are sympathetic to the changes in the FOMC’s policy strategy that promote patience and that focus on average inflation. Whether these evolutionary changes bring improvements depends critically on the ability of the Committee to clarify both their medium-term inflation objective and to elaborate their strategy for addressing unpleasant upside inflation surprises. In other words, for the combination of FAIT and the patient shortfall strategy to be effective in maintaining price stability and maximum sustainable growth, the FOMC will need to first agree and then communicate a complex, time-varying approach to setting monetary policy. For a committee of 19 people, this is a difficult, but not insurmountable, task.