The ECB's New Strategy: Codifying Existing Practice . . . plus

“A long period of low price pressures, and years of repeated overprediction of the future path of inflation require that higher inflation prospects need to be visibly reflected in actual underlying inflation dynamics before they warrant a more fundamental reassessment of the medium-term inflation outlook.” Isabel Schnabel, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, “A new strategy for a changing world,” July 14, 2021.

When the ECB began operation in 1999, many observers focused on its differences from the Federal Reserve. Perhaps the most widely cited distinction is the one between the ECB’s “hierarchical mandate” (which sets price stability as its primary goal) and the Fed’s “dual mandate” (which puts the price stability and full employment on an equal footing).

Yet, since the start, the ECB was much like the Fed. The most apparent similarity is its governance structure. In both, policy decisions belong to a group that combines a small core (the ECB’s Executive Board and the Federal Reserve’s Board of Governors) and a larger number of regional representatives (the heads of the euro-area national central banks and the U.S. Reserve Bank presidents).

Over the past two decades, the ECB and the Fed have learned a great deal from each other, furthering convergence. One example is the evolution of their transparency policy and communications tools. Indeed, the ECB now publishes meeting summaries analogous to the Fed’s minutes, while the Fed chair now holds a post-policy-meeting press conference, something the ECB has done from the start. The two central banks also faced common shocks—including the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2007-09 and the ongoing pandemic—that led them to introduce similar nonstandard policy tools, including forward guidance and large-scale asset purchases.

Against this background, it is unsurprising that the broad monetary policy strategies in the United States and the euro area converged as well. On July 8, the ECB published the culmination of the strategy review that began in early 2020, the first since 2003. The implementation of the new strategy comes nearly one year after the Fed revised its longer-run goals in August 2020 (see our earlier posts here and here).

If past is prologue, observers will exaggerate the differences. Perhaps most obvious, unlike the Fed, the ECB’s strategic update did not introduce an averaging framework in which they would “make up” for past errors. Nevertheless, we suspect that it will be difficult to distinguish most Fed and ECB policy actions based on the modest differences in their strategic frameworks. For the most part, both revised strategies codify existing practice, as they permit extensive discretion in how they employ their growing set of policy tools. And, going forward, both central banks likely will continue to face strong forces promoting convergence: these include a combination of common policy objectives, long-term global trends, and shared analytical methods.

In our view, the key drivers of policy differences between the two central banks will remain the distinctive financial and fiscal systems in which they operate: unlike the ECB, the Fed conducts its operations mostly in “safe” assets that trade in a deep, liquid, and integrated financial market. And, when it comes to countering deflationary threats, the Fed needs to coordinate its action with just one powerful fiscal agent—the U.S. Treasury—rather than the governments of 19 member states.

In this post, we summarize the motivations for the ECB’s new strategy and describe three notable changes: target 2% inflation, symmetrically and unambiguously; integrate climate change into the framework; and outline a plan to introduce owner-occupied housing into the price index they target (the euro area harmonised index of consumer prices). While the new strategy can help the ECB achieve its price stability mandate, in our view the overall impact of the revisions is likely to be modest.

Starting with the strategic motivations, the most important are the same as the ones that drove the Fed’s review: the long-term declines in both inflation and real interest rates that lowered equilibrium nominal interest rates and prompted long episodes of policy rates at or below zero.

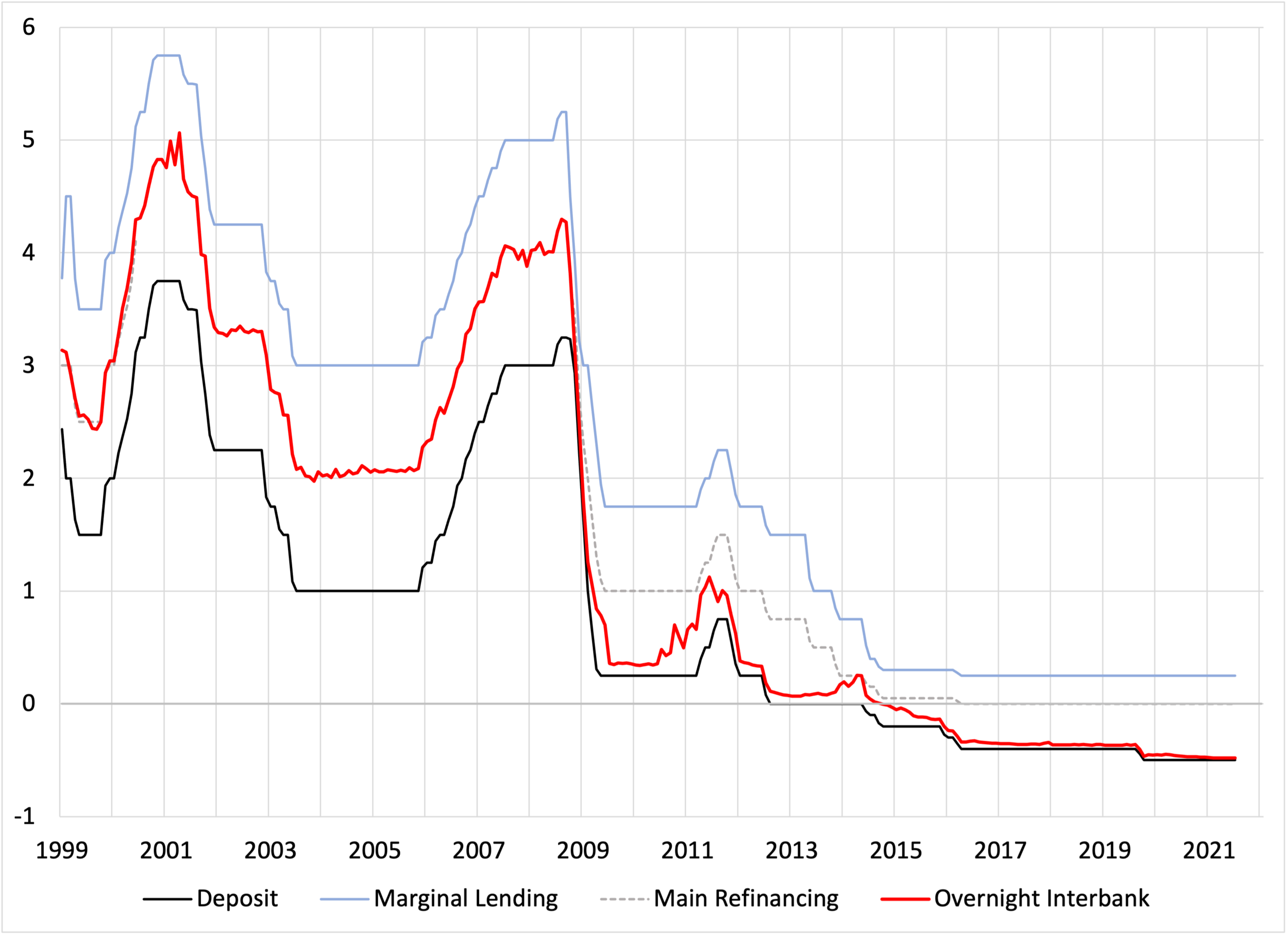

Indeed, as the chart below highlights, the ECB has kept its deposit rate (black line, equivalent to the Fed’s interest rate on reserve balances) below zero since mid-2014. Moreover, it last raised this rate a decade ago in 2011. Faced with extended periods with the policy rate at or below zero, the central bank needs additional tools (including forward guidance and balance sheet measures) to achieve its stabilization objectives. It also probably needs cooperation from other policymakers—including fiscal and regulatory authorities.

ECB policy rates (monthly averages), 1999-July 2021

Source: ECB.

The ECB traces part of this enduring downshift of policy rates to long-run structural trends (including demographics and globalization) that lowered the global equilibrium real (or natural) rate of interest, known as r*, by between 1½ and 2 percentage points (see our earlier posts here and here). But it also reflects the failure of aggressive monetary stimulus—including negative interest rates, forward guidance, and the purchase of trillions of euros of bonds—to bring inflation back to target. As the following chart demonstrates, even with the ECB’s deposit rate at or below zero, the five-year euro area inflation rate has been below 2% since 2012.

Euro-area inflation (Annualized percent changes vs 1 year and 5 years ago), 2004-July 2021

Source: Eurostat.

Against this background, the revisions to the ECB’s strategic framework are designed to enhance its stabilization tools in the absence of conventional interest rate policy space. With policy rates likely to be stuck at or below zero for extended periods, the strategy makes clear that the formerly unconventional—“forward guidance, longer-term refinance operations, negative interest rates, and asset purchases”—is now conventional.

For similar reasons, the new strategy sets the ECB’s inflation target unambiguously at 2%. The previous asymmetric objective of “below, but close to 2%” encouraged some to view 2% inflation as a cap, rather than a norm. Perhaps as a result, inflation expectations lingered below 2%, limiting the central bank’s ability to lower real interest rates.

Against that background, it is perhaps surprising that the ECB did not take the next step, following the Fed, and introduce a make-up strategy to help raise inflation expectations following long periods of sub-target price increases. Like price-level targeting, the Fed’s flexible average inflation targeting (FAIT) aims explicitly for a period of above-target inflation to correct for past shortfalls (and vice versa for past inflation overshoots). In theory, building these prospective inflation overshoots and undershoots into economywide expectations creates stabilizing swings in the real interest rate, even with the policy rate stuck at zero. In practice, however, the Fed has not made clear either the look-back period for determining an inflation shortfall, or the restoration period for correcting it. Consequently, the strategy’s equilibrium impact on inflation expectations probably will depend on what the Fed actually does going forward (see our earlier discussion here).

In the ECB’s case, as the new strategy makes explicit, continued emphasis on the medium term allows policymakers a great deal of latitude to achieve comparable results. As the opening citation from ECB Executive Board Member Isabel Schnabel suggests, we think the key word is “patience.” According to the strategy statement, for example, following “an adverse supply shock, the Governing Council may decide to lengthen the horizon over which inflation returns to the target level in order to avoid pronounced falls in economic activity.” Or, in another circumstance at the effective lower bound: “faced with large adverse shocks the ECB’s policy response will […] include an especially forceful use of its monetary policy instruments” that may “imply a transitory period in which inflation is moderately above target.” Given this wide degree of discretion, just as with the Fed’s new strategy, what observers come to expect about future inflation will depend largely on the ECB’s actions in coming years.

The ECB’s revised strategy addresses many other points, including the need for cooperation with fiscal policymakers amid deeply adverse shocks, the “complementarity” of price stability and full employment, and the importance of financial stability considerations. Again, for the most part, the framework is consistent with greater convergence with Fed policy. A particularly good example of this is in the ECB’s revised analytic approach that explicitly drops the “two-pillar” approach where monetary analysis using measures of money served as a “cross check” on the economic analysis based on everything else. The new “integrated” approach, which is largely consistent with practices in place for some time, focuses on a broad assessment of both economic developments, on the one hand, and of monetary and financial developments, on the other. In the ECB’s case, the latter aims explicitly at assessing financial stability and possible impediments to monetary policy transmission (see slide 10 here).

In one notable area—addressing climate change—the ECB’s strategy is more explicit than the Fed’s. However, the plans, which focus on improving economic modeling, developing new indicators regarding the climate footprint of intermediaries, considering climate risks for the financial system, and ensuring climate neutrality for the central bank’s portfolio, are consistent with recent Fed evolution in this area. Indeed, in a virtually parallel development earlier this year, the Fed created both a Supervision Climate Committee and a Financial Stability Climate Committee to ensure the resilience of U.S. intermediaries and the financial system (see here).

We find one other, largely technical, element of the new ECB strategy, worth mentioning: the plan to change the measurement of inflation itself. Unlike most advanced economies, the ECB’s key metric for price stability—the harmonised index of consumer prices (HICP)—does not incorporate owner-occupied housing (OOH). In contrast, in the United States, the imputation of rent to owners—something that we cannot directly observe—is the largest single component of the consumer price index, accounting for nearly 24% of the total and 30% of the ex-food-and-energy component. (Due to its large weight, “owners’ equivalent rent” plays an central role in statistical measures of U.S. core inflation, including the trimmed mean and the median, so it has significant influence on Fed policy. See here.)

Discussions about including OOH in the HICP are at least 15 years old (see Eiglsperger, pages 68-79). In our view, there are strong theoretical and practical reasons for moving decisively in this direction. Indeed. with parts of the euro area facing an extended house price boom amid persistently low interest rates (see Kindermann et al), households may come to question the credibility of the HICP as a measure of inflation. (For a general discussion of housing in inflation measurement, see here).

Fortunately, Eurostat now publishes an index (unlike the U.S. imputed rent measure) based on actual transaction prices for new homes. As the chart shows, since 2015, inflation in this OOH measure exceeded that of the HICP by nearly 2 percentage points annually.

Euro Area: HICP vs OOH Price Index, 2010-2Q 2021

Note: OOH Price Index available only through 1Q 2021. Source: Eurostat.

Depending on its weight, including OOH can have a large or a small impact on the HICP. For example, if we use the U.S. weight of 24%, as in Gros, the average annual inflation from Q1 2015 to Q1 2021 rises from 1.09% to 1.56%—much closer to the ECB’s 2% target. But, following Nell et al, who use the 9% weight reported by Eiglsperger and Goldhammer, average inflation over the same six-year period only rises by only 0.17 percentage points.

Against this background, the ECB’s strategy regarding OOH seems largely aspirational. While the framework review includes a plan to incorporate quarterly developments in the cost of housing in its policy deliberations in coming years, there is only a very loose roadmap for adding a specific component to the monthly HICP. As far as we can tell, this OOH debate probably will remain a live one when the ECB again revisits its new strategy—currently expected in 2025. By then, one can only hope that the proof of the broader strategy already will be in the pudding.

This brings us back to where we started. We applaud the ECB for undertaking a comprehensive and thoughtful review of their monetary policy framework. After studying the results, our conclusion is that the changes are modest and incremental, largely reinforcing adjustments that accumulated gradually over the last dozen years. Given that central bankers are conservative by nature, it is unsurprising their policy framework would evolve slowly. Nevertheless, every central bank should have such a periodic review at least once a decade. We look forward to reading the results of the next ECB review five years from now.