Trump's Tariffnado

“[… I]n times of recession, the trade deficit goes down. So, if the tariffs push us into recession, we could reduce the trade deficit because we’re all buying less stuff.”

Senator Rand Paul (R-Kentucky), CNBC Squawk Box, April 8, 2025.

Since his mid-January inauguration, President Trump has introduced tariff hikes that are unprecedented in scale, breadth, and speed. Even after the 90-day partial postponement announced on April 9, the Yale Budget Lab estimates that the average U.S. tariff rate is now 27 percent, the highest level since 1902 (see chart)! While the rate likely will fall closer to 18 percent as U.S. purchases of high-tariffed goods decline, that would still be the highest level since 1933.

Currently, the Trump tariff regime includes a whopping 145% duty on China, a 10% duty on most other countries and high tolls on specific industries, including 25% duties on automobiles, steel, and aluminum. Going forward, the President could restore the postponed tariffs, raise those on products that have so far been spared (e.g. copper, lumber, pharmaceuticals, and semiconductors), further increase levies on countries that (like China) opt to retaliate, or reach agreements with some countries to lower tariffs and other obstacles to trade. Regardless of what comes next, reliable analysts already view the Trump levies as the largest federal tax hike at least since 1982 (see here).

United States: Average Tariff Rate on U.S. Imports (annual), 1820-2025

Sources: Tax Foundation (data through 2024), Yale Budget Lab for April 9 and post-adjustment estimates. The latest estimate does not reflect the exclusion from tariffs of some electronics imports that was announced on April 12.

Perhaps the most amazing thing about the tariffs is that no one outside the Administration knows why they have been applied. Of course, President Trump has advocated high tariff walls for decades. In that fundamental sense, these actions are unsurprising. Nevertheless, the equity market crash following the April 2 tariff announcement, as well as the increase in U.S. Treasury yields and the fall in the value of the dollar, confirms that investors dramatically underestimated both the extent of the Trump tariffs and their potential economic damage.

The fact that Administration officials are voicing numerous inconsistent rationales for the tariffs is a key reason for the financial market shock. For example, if tariffs are to raise tax revenue over the long run, they need to be virtually permanent. Similarly, if they are to prompt the import substitution that might boost domestic manufacturing production and employment, they must be permanently (and predictably) high. Yet, some officials insist that the policy strategy is to create leverage for negotiation with trading partners, leading to a mutual reduction of trade obstacles that boosts cross-border activity. But if that is the goal, the tariffs will neither raise much revenue nor motivate domestic firms to invest in sectors where the nation lacks underlying competitive advantage. Finally, the sky-high tariff on China suggests that national security is a key objective. However, the President also raised tariffs sharply on U.S. military allies and their key products, undermining the security benefits of an integrated market in North America. This extraordinary incoherence is clearly bad for the economy, the financial system and national security.

Then there is the President’s April 9 postponement. Surely, the Administration had the option on April 2 to announce specific tariffs and delay their implementation for 90 days conditional on bilateral negotiations. Instead, implementing the tariffs and then backing down amid financial turbulence suggests a “Trump put” (e.g. downside insurance) for financial markets, reducing any negotiating leverage the Administration might have created a week earlier. The widespread impression is the President blinked on April 9 in response to the combined equity, bond , and currency market disruptions that signaled declining trust in U.S. assets overall (see, for example, here and here). In short, trade policy has become erratic and unpredictable.

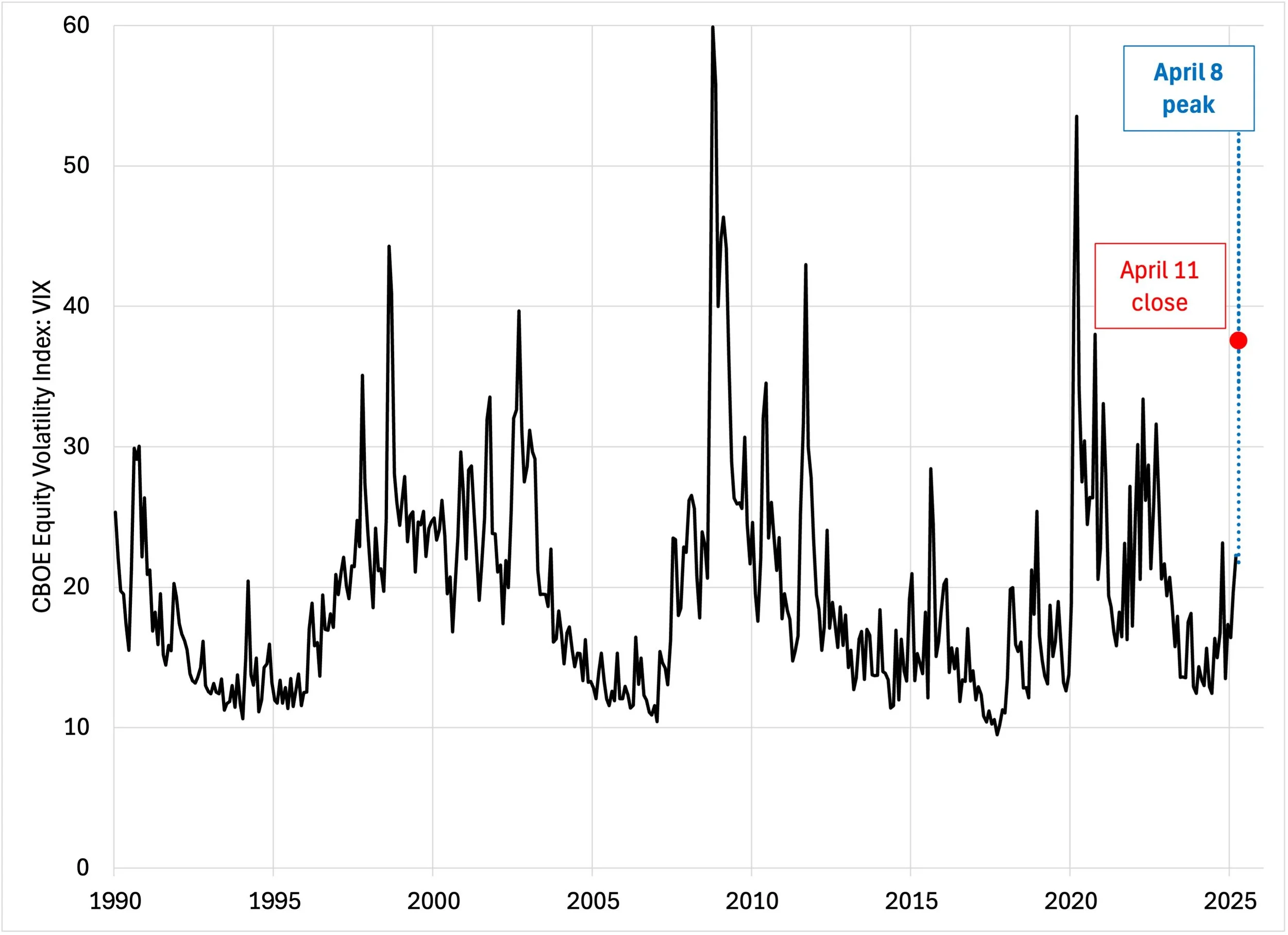

These fundamental uncertainties about the purpose of the tariffs (and whether there is any logical explanation for the President’s actions) mean that we still have little idea how high the tariffs will go or how long they will last. Even before the President’s April actions, one well-known measure of U.S. economic policy uncertainty had reached its second-highest level over the past 40 years (see the news index here). In recent days, more up-to-date measures of uncertainty soared to levels that generally are seen only in periods of wars, pandemics and financial crashes. For example, the VIX, which uses options to measure expectations for volatility in the S&P 500 over the coming 30 days, peaked over 50 on April 8, closing at 37.6 on April 11 (see chart).

CBOE Equity Market Volatility Index (VIX, month-end to March 2025, then daily), 1990-April 11, 2025

Source: FRED through April 10, 2025. Yahoo Finance for April 11, 2025.

The problem for equity investors is not some complex trade-off between the short-run costs of the tariffs and their long-run benefits. Investors discount expected profits over the full horizon. Consequently, the equity market plunge since the inauguration, and especially since April 2, anticipates a very negative impact on firm profits even over the long run. This adverse market judgment is consistent with economic theory: tariffs undermine incentives to compete and innovate, eventually shifting resources into less-productive activities. The heightened volatility of the equity market mostly reflects uncertainty over the future path of the tariffs. Keeping them in place (even without any further increases) is likely to lead to stubborn inflation and lower long-term growth. Moreover, record trade policy uncertainty alone probably is sufficient to induce a recession.

We should add that experience with high tariffs in modern economies bodes very poorly for the U.S. economic outlook. In the 1950s and 1960s, some economists called for “import substitution” as a growth strategy in the emerging world (see, for example, Raul Prebisch). Replacing Mercedes produced in Germany with Cadillacs from Michigan may be one goal of the new U.S. tariffs. However, based on the experience in places like Argentina and India, the general strategy of import substitution is now widely viewed as a historic failure. If anything, this approach made countries poorer, eventually giving way to policies emphasizing greater openness to trade and foreign equity investment, and (in some cases) lower taxation and regulation (see, for example, here). Rather than import substitution that impedes competition, it is competition-enhancing policies that generally fuel economic growth and raise standards of living.

In the remainder of this post, we try to correct a common misunderstanding about international trade policy: namely, that higher tariffs, by promoting import substitution, will reduce the U.S. external deficit. As Senator Paul suggests in the opening citation, the primary mechanism by which tariffs can narrow the external deficit is by inducing a recession. Indeed, as the chart below highlights, the U.S. current account balance—which reasonably approximates the nation’s trade balance—rises during recessions and declines in expansions.

United States: Current Account Balance (Quarterly, Percent of GDP), 1980-2024

Notes: Gray shading denotes recessions. Source: FRED.

To build the case, we first introduce the national account definition of output or income (GDP, or Y) and show how it relates to private saving (S) and public saving (T - G). The latter is the difference between tax revenues T and government spending G, which equals the government’s budget balance. National saving is the sum of private (S) and public (T - G) saving. This accounting shows that the external balance (the current account surplus or deficit) equals the excess of national saving (S + T - G) over investment (I). The key implication is that altering the external balance requires change in some combination of private saving, the government budget balance, and investment.

To see this, we take a short detour into some simple accounting starting with the familiar textbook definition of national output:

Y = C + I + G + NX

In words, a nation’s production or income (Y) is the sum of consumption (C), Investment (I), government spending (G), and net exports (NX). The external balance equals net exports (exports minus imports). When NX is positive, there is a current account surplus and when it is negative, there is a deficit.

Next, note that the private sector can either consume (C) or save (S) its after-tax income:

Y – T = C + S

Putting these two definitions together (subtracting one from the other and rearranging), we can write

S + (T – G) – I = NX

Once more, the second term on the left-hand side of this equation is the government budget balance: the excess of tax revenue (T) over expenditure (G). When this is positive, the government is running a surplus and when it is negative, there is a deficit. Again, summing public saving (T – G) and private saving gives us national saving: S + (T – G).

While this arithmetic is simply accounting, it contains an important lesson: the current account (NX) must equal the difference between national saving [S+ (T – G)] and investment (I). When investment exceeds national saving, the nation has a current account deficit (NX < 0). And when national saving exceeds investment, the country has a current account surplus (NX > 0).

Put differently, there are three possible sources of funding for investment: private saving (S), public saving (T – G), or foreigners in the form of negative net exports (NX < 0). In a country like the United States, where the last current account surplus occurred during the 1990-91 recession, investment is persistently greater than national saving.

We can now see the key result: to narrow the U.S. external deficit, the nation must either increase national saving (private plus public), reduce investment, or some combination of the two. Which of these outcomes, if any, are likely to result from a rise in tariffs?

Let’s start with the components of saving: government and private (the latter combines households and firms). As taxes, tariffs do raise government saving (T – G). However, the Administration and Congress also plan large tax cuts that are likely to negate this effect. Alternatively, will tariffs raise private saving? Again, this is unlikely. Saving generally depends on long-run factors like population aging. It also may be sensitive to the growth of after-tax income (which typically boosts saving) and inflation (which typically lowers saving). Since tariffs tend to lower after-tax income and raise inflation, this would seem to depress, not raise, saving.

So, the principal means by which the Trump tariffs are likely to affect the gap between national saving and investment is by lowering investment. Since tariffs tend to lower profit, they are likely to lower investment, too. Like profit, business investment is highly procyclical: it typically plunges in a recession and booms in a recovery (see here). Not surprisingly, that also makes the external balance highly countercyclical, rising in recessions as investment falls (as Senator Paul states in the opening quote) and falling in recoveries as investment rebounds.

The national accounting framework also points to problems with other Administration claims. Even if tariffs motivate some foreign investment in the United States, they are unlikely to raise overall investment. Ironically, if they did so, the effect at least temporarily would be to lower, not raise, the U.S. external balance: if I goes up and national saving is stable, then the external balance goes down.

We conclude by pointing out another extremely damaging mechanism by which the new tariff regime could narrow the U.S. trade deficit: namely, by reducing the attractiveness of U.S. assets to foreign investors. So far, we have focused on the nation’s trade account—its exports and imports of goods and services. The flip side of the trade account is the capital account: the flow of assets across borders that compensate the domestic or foreign sellers of goods and services.

When foreigners sell the United States more goods and services than they purchase, the sellers must accept U.S. assets as compensation. With a view that U.S. assets are very high quality, foreigners have been very willing to accumulate them. In fact, the net liability position of the United States – the excess of foreign ownership of U.S. assets over American ownership of foreign assets – currently exceeds $25 trillion (nearly 90% of GDP).

Among other things, the willingness of foreigners to purchase and hold such a large quantity of U.S. assets reflects the perception of the nation’s dynamic business sector, its predictable and effective policy responses to risk, and its reliable protection of property rights under the rule of law. As one consequence, when financial turbulence occurred in the past, investors around the world generally treated U.S. Treasury debt as the very safest asset available.

However, introducing an erratic and incoherent tariff regime raises doubts about the quality of U.S. policy management and potentially about the property rights protections accorded to foreign investors. Suppose, for example, that foreigners reasonably expect what our national accounting arithmetic indicates: that, in the absence of a recession, even a tariffnado will fail to narrow the U.S. external deficit. Will fears arise that U.S. policymakers might try even more aggressive interventions to achieve external balance? For example, would the Trump Administration put in place policies aimed at impeding the foreign capital inflows needed to finance the external deficit in goods and services? In November 2024, the current Chair of the Council of Economic Advisers Stephen Miran outlined one such policy that would impose a “user fee” (i.e. tax) on foreign holdings of U.S. Treasury debt (see here).

Unfortunately, fears of such extraordinary government intervention in the U.S. capital account themselves pose a serious risk to U.S. economic stability. The vulnerability is clear: aware of the nation’s large net liability, worried foreigners could seek to reduce their exposure to U.S. assets before it is too late. That is, they may wish not only to slow their acquisitions – narrowing the external deficit – but also to sell existing holdings.

Such a balance-of-payments crisis is known as a “sudden stop.” To meet any precipitous desire by foreigners to withdraw from the United States, the nation suddenly would have to save more than it invests. In practice, such a rapid shift occurs through a plunge of investment and a deep recession, together with some combination of a collapse in the value of the currency and a fall in domestic prices. This is what happened in many emerging economies in the 1990s, as well as in the economies of southern Europe in the 2010s. (See our primer on sudden stops.)

Fortunately, despite the nation’s persistent external deficit, there has been little reason to fear such extreme outcomes in recent decades. The question now is whether the President’s tariff debacle will crack open this Pandora’s box.