Why the mortgage interest tax deduction should disappear, but won't

In the run-up to the 2012 U.S. Presidential election, Planet Money asked five economists from across the political spectrum for proposals that they would like to see in the platform of the candidates. The diverse group agreed, first and foremost, on the wisdom of eliminating the tax deductibility of mortgage interest.

The vast majority of economists probably agree. We certainly do. But it won’t happen, because politicians with aspirations for reelection find it toxic.

What inspires us to discuss this now? An important anniversary in our profession’s understanding of economic policy. Forty years ago, in his celebrated book Equality and Efficiency: The Big Tradeoff, Arthur Okun explained how many policy choices involve a tradeoff between the distribution of income and the size of the economy. That is, the more redistributional a policy, the more of a drag it is on growth.

While much of tax policy works this way, the tax deductibility of mortgage interest does not: it both raises inequality and reduces economic efficiency.

The source of increased inequality is simple. The private benefits of the mortgage interest deduction rise both with a person’s income and with the cost of their house. The higher your income, the higher your marginal tax rate; and the bigger your house, the bigger the possible mortgage. When either rises, the value of the tax deduction rises, too.

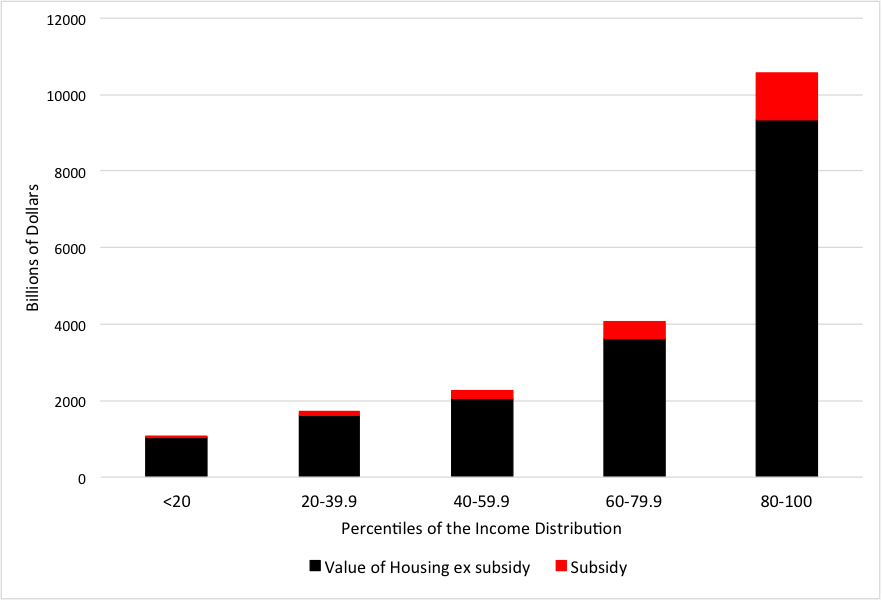

To see how the benefits are distributed across the more- and less-well off, we turn to the Federal Reserve’s 2013 Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF). From the data there, we can construct the following graph, which shows the extent to which the people with the highest incomes receive the biggest subsidies.

Value of owner-occupied housing by income quintile (Billions of U.S. dollars)

Source: Federal Reserve Board, Survey of Consumer Finance 2013, and authors' calculations.

To understand the figure, start by noting that the U.S. residential housing stock had a total value of nearly $20 trillion at the end of 2013. Using the SCF data, we estimate that the present discounted value of the mortgage interest tax break exceeds $2 trillion. Importantly, the distribution of this $2 trillion benefit is extremely unequal. Fully 60% of it goes to households in the top 20% of the income distribution, and less than 2% to households in the bottom 20%. In other words, this is a highly regressive policy, benefiting the rich much more than the poor. (The technical note at the end of this post discusses some of the assumptions behind these calculations.)

Aside from inequality concerns, there are other powerful reasons to dislike the mortgage interest deduction. Above all, it is inefficient. By subsidizing bigger, more expensive houses, the policy misallocates scarce savings away from productive investments that raise living standards through income- and job-creating innovations. It also makes our financial system more vulnerable: as we wrote in an earlier post, it encourages people to take on risks – in the form of large, subsidized mortgages – that they are not equipped to bear. In the recent crisis, risky mortgage debt was sufficient to put the entire financial system at risk.

All of this leads us to conclude that the mortgage interest deduction is one of those cases where there is no tradeoff. Eliminating it would improve both equality and efficiency, enhancing economic growth and making our financial system more resilient.

Unfortunately, the tax deductibility of mortgage interest is here to stay. Nearly 50 million U.S. households currently have mortgages, and politicians don’t wish to alienate them.

But the borrowers are only the most obvious beneficiaries. In fact, all homeowners would suffer if the mortgage deduction were eliminated. The reason is that the value of everyone’s house would fall, not just the ones of the people with mortgages. In any market – including housing – prices are determined by the marginal buyer. The marginal home buyer – no longer subsidized by the mortgage interest tax deduction – would find housing much less attractive: the loss of marginal value significantly exceeds the “average benefit” to the subsidized borrowers we described above.

A simple computation allows us to estimate the economy-wide impact. Start by assuming that home prices are determined by someone who puts 20% down, borrows 80%, and has a 25% marginal tax rate. (We are being conservative, as many people make smaller down-payments and face higher marginal tax rates.) Under these assumptions, for each $100,000 in the home price, the marginal buyer borrows $80,000. As we explain in the technical note, the present value of the tax subsidy is just this $80,000 times the homeowner’s marginal tax rate of 25% – or $20,000. In other words, the tax subsidy enables our hypothetical marginal home purchaser to pay an additional 20% for a house. Eliminating the tax deductibility of mortgage interest would reduce home prices by this amount.

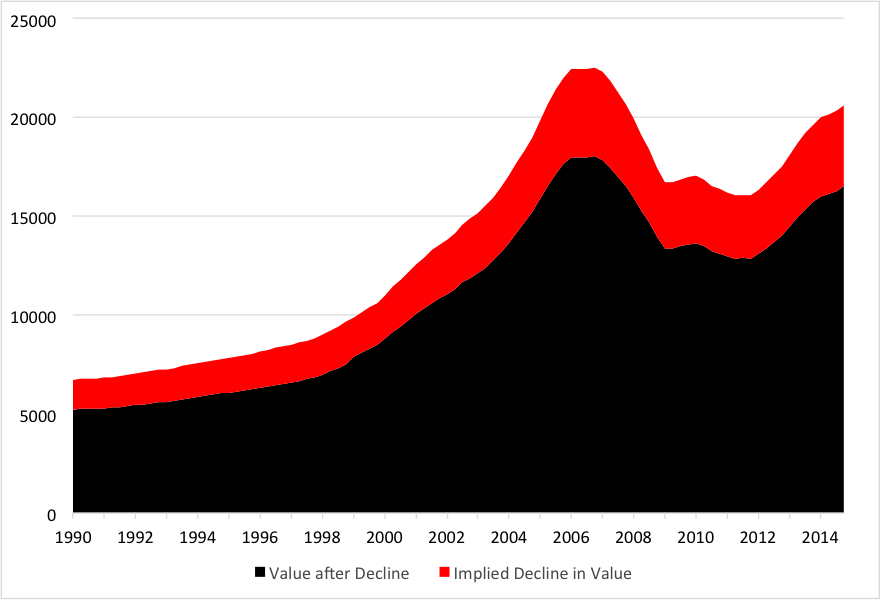

The unpleasant implications for homeowners can be seen in the next chart where we plot the value of household real estate since 1990. We divide this into two parts: the portion that is due to the interest subsidy and the unsubsidized portion. If the subsidy were eliminated, homeowners would lose the quantity that is shaded in red – or currently about $4.1 trillion. This exceeds the $2-trillion value of the tax break estimated earlier partly because it affects all homeowners, even those who have no mortgage or whose mortgage does not qualify for the tax deduction. For comparison, the plunge of real estate value from the 2006 peak to the 2011 trough was $6.4 trillion.

Value of owner-occupied real estate (Billions of U.S. dollars)

Source: Federal Reserve Board Flow of Funds combined with U.S. Treasury Internal Revenue Service tax rates, and authors' calculations. This measure includes vacant land, so it overstates the impact of the tax deduction.

Aside from the contractionary impact on the economy, many people would see such a drop in house prices as dramatically unfair. It’s true that the biggest losers in monetary terms would be the owners of the most valuable (oversized) houses; but the less well-off would suffer, too. While it is a progressive policy, all 80 million households that own homes would take a hit.

It is tempting to just give up and admit political defeat, but there may be a way out. Our suggestion is to build on past reforms that capped the tax deduction by limiting the size of eligible mortgages. Currently, interest payments on mortgages of up to $1 million are deductible. Why not lower that number? Since roughly 10% of U.S. homes are worth more than $500,000, our proposal is to set the limit at the interest payments on a $400,000 mortgage (indexed appropriately). This would promote both efficiency and equality.

With Art Okun in mind, what broader political economy lesson do we draw from this example? Policies that provide asset owners large “rents” (payments unwarranted by the scarcity of the asset itself) are incredibly difficult to eliminate, even when they are both unfair and inefficient. Such rents create an entire ecosystem of beneficiaries (in this case, ranging from construction firms and workers, to real estate brokers, to mortgage lenders and borrowers) who constitute a powerful political constituency blocking almost any reform. Even when there is no Okun tradeoff, change is difficult.

Hopefully, experience and education will keep us from going down this road too often. Try listening to those Planet Money podcasts.

Technical note: In computing the net present value of the mortgage interest deduction, we make a series of simplifying assumptions. As we mention in the text, we assume borrowers put 80% down and face a 25% marginal tax rate. We also ignore state income taxes. These assumptions lead us to understate the private benefits and the economic distortions resulting from the tax deduction. At the same time, our present value calculation assumes that mortgages are interest only and that payments can be discounted at the same rate as the lender is charging. This simplification means that the present value of the deduction is just the value of the house times the tax rate. This assumption overstates the benefits from the tax deduction because it treats principal payments as eligible interest payments. The lower the interest rate and the shorter the mortgage duration, the greater the overstatement. Finally, in assessing the distribution of private benefits from the mortgage interest rate deduction, we assume that all benefits accrue to the homeowner, but lenders likely garner a portion in the form of higher lending rates.