Ending Too Big to Fail: Resolution Edition

“…the ability of U.S. regulators to assume control of the resolution process may be required to elicit cooperation from non-U.S. regulators in countries where a recapitalized SIFI operates.” Jane Lee Vris, Chair, National Bankruptcy Conference, March 17, 2017

“Frankly, if we were left with a bankruptcy-code only solution [in the United States] it would be worrying.… We would have to [ask if] we really think there is a resolution mechanism in there that…has got what it needs to be effective.” Andrew Bailey, CEO, UK Financial Conduct Authority, cited in FT, April 23, 2017

The failure of Lehman on September 15, 2008, signaled the most intense phase of the Great Financial Crisis of 2007-2009, fueling a run on a broad array of intermediaries. Following Congress’ approval of TARP funding that was used mostly to recapitalize U.S. financial firms, the mantra of U.S. regulators became “…we will not pull a Lehman” (Financial Crisis Inquiry Report, page 380). Thereafter, to ensure that another large institution did not fail, policymakers chose bailouts to contain the crisis. As a result, today we still have intermediaries that are too big to fail.

The autumn 2008 experience convinced many observers of the need for a robust resolution regime in which financial behemoths could be re-organized quickly without risk of contagion or crisis. The question was, and remains, how to do it. Dodd-Frank provided a two-pronged answer: the FDIC would first rely on the bankruptcy code (Title I), and second, on a resolution temporarily funded (if necessary) by government resources (Title II). The second piece is commonly known as Orderly Liquidation Authority (OLA), which is funded by the Orderly Liquidation Fund (OLF). (It would be more accurate to label these as a resolution authority and a resolution fund, since they are intended to reorganize and restructure, rather than liquidate the firm in question.)

In response to dissatisfaction with parts of this solution, Congress and the President are working on refinements. Last month, the House passed a bipartisan revision of the bankruptcy code (Financial Institutions Bankruptcy Act, or FIBA) that would expedite the resolution of adequately structured intermediaries. And, on April 21, President Trump ordered a Treasury review of OLA, expressing concern that the OLF authorization to use government funds “may encourage excessive risk taking by creditors, counterparties, and shareholders of financial companies.”

This post considers FIBA and how it fits in with the existing Dodd-Frank mechanism. To summarize, FIBA buttresses the first element—making credible its reliance on the bankruptcy code. However, it does not substitute for essential parts of the second: (1) the authority to use temporary government funding (OLF); and, (2) the ability to work directly with foreign regulators in cases (like Lehman) involving extensive operations abroad.

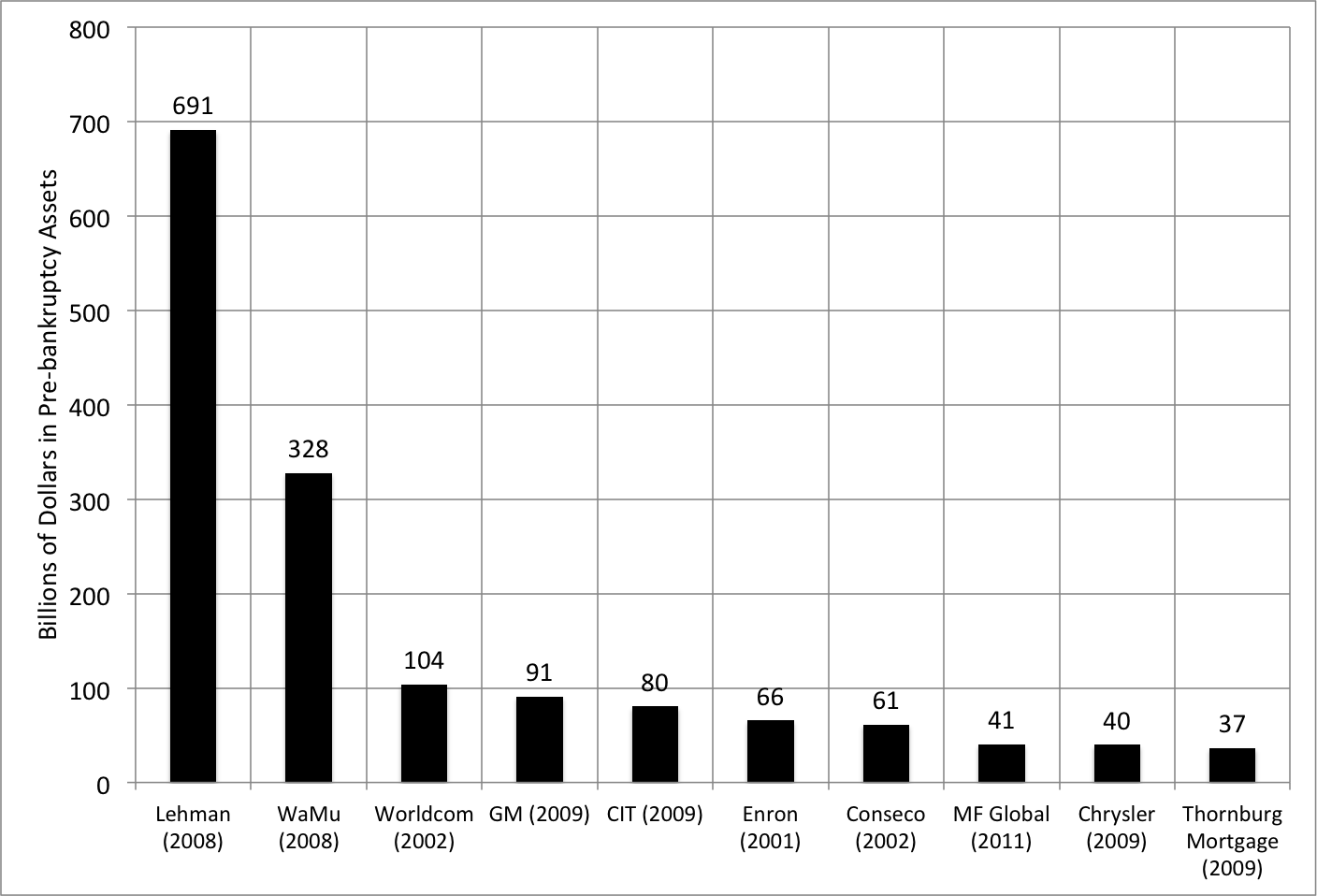

Let’s start with a bit of background on U.S. bankruptcies. The chart below shows that at least 6 of the top 10 U.S. bankruptcies (ranked by pre-bankruptcy assets) were those of financial intermediaries (if Enron is treated as a financial institution, which it largely was by the time of its failure, then the count is 7 of 10). The Lehman bankruptcy, for which court proceedings are still ongoing, stands apart due to its size, complexity and international nature: it was larger than the next five combined. Unsurprisingly, bankruptcies often result in large losses to creditors: after more than 8 years, senior Lehman bondholders have recovered about 42 cents on the dollar.

Top 10 U.S. corporate bankruptcies by pre-bankruptcy assets (Billions of dollars)

Source: Infoplease.

In the case of a systemic intermediary like Lehman, the familiar problem with standard reorganization bankruptcy procedure (“Chapter 11”) is that it takes far too long. Runs turn into panics almost immediately, so the failure of one intermediary can spread to others in the blink of an eye. (See Kapur for a description of bank runs as the outcome of a prisoners’ dilemma).

For years, academic specialists in bankruptcy law have been working on a revision of the code that would permit the speedy resolution of large, complex financial intermediaries (LCFIs). Labeled “Chapter 14”, their solution presumes that institutions will have both an appropriate legal and capital structure. For example, revised versions of Chapter 14 are designed for LCFIs that are organized as a hub-and-spoke operation under the aegis of a financial holding company (FHC), and have sufficient long-term and subordinated debt that can be written down to recapitalize the institution during the process. (See Jackson (2015) for a recent update of Chapter 14.)

The Chapter 14 idea, now embedded in FIBA, relies on specialized bankruptcy judges to undertake the re-organization of an LCFI over the course of a weekend. The key to this system is its focus on the FHC. This allows for a single domestic legal proceeding, leaving all the subsidiaries to continue operating (in stark contrast to the dozens of proceedings for Lehman and its subs). Provided that the process is rapid, well-managed, and credible, the advantages of a bankruptcy procedure are substantial. The fact that they are based on decades of court testing of property rights under the bankruptcy code makes them predictable. And, since they are court proceedings, they would clearly be consistent with the rule of law.

Several recent developments make a Chapter 14 bankruptcy approach to resolution more feasible than it would have been a decade ago. The most important are the requirements that LCFIs: (1) create “living wills,” and; (2) issue significant amounts of long-term, unsecured debt. On the first, Adler and Philippon argue in Regulating Wall Street: CHOICE Act vs. Dodd-Frank that living wills, which oblige systemic intermediaries to detail how they can be quickly and safely resolved, can be useful guides for resolution if they specify how long-term debt is to be used to re-capitalize an insolvent intermediary. Related to this is the requirement for Total Loss Absorbing Capital (TLAC). In December 2016, the Federal Reserve Board implemented a rule requiring systemic intermediaries to issue long-term and subordinated debt that, together with common equity, would create a minimum loss absorption capacity equal to 18% of risk-weighted assets or 7.5% of total assets.

We should emphasize that the FDIC’s current strategy (under Dodd-Frank) for resolving a systemic intermediary closely resembles the Chapter 14 approach embodied in FIBA. Dubbed “single point of entry” (SPOE), it is intended to complete the reorganization over a weekend and is designed to work through the FHC, allowing uninterrupted operations of the subsidiaries.

One difference between the two methods is that, by focusing on court processes, Chapter 14 curtails regulatory discretion. As it stands, Dodd-Frank permits the FDIC to favor one creditor over another (subject to the proviso that no creditor be worse off than in a standard Chapter 11 bankruptcy). John Taylor, in his recent testimony regarding FIBA, argues that the FDIC’s authority to provide select creditors more funds than they would receive in bankruptcy—perhaps to limit contagion—adds uncertainty to the process and diminishes effective counterparty discipline in normal conditions.

This leads us to our first conclusion: transferring the resolution process from the FDIC to the courts has significant benefits. We also expect that it will enhance public support, which is all for the better.

But Dodd-Frank does more than FIBA: it created the OLA and OLF as well. In this sense, FIBA complements, rather than substitutes for Dodd-Frank. What most distinguishes Dodd-Frank from a pure Chapter 14 mechanism is OLF—the availability of temporary government funding. No intermediary, except for one that is 100% equity funded, will have adequate loss-absorbing capacity in every possible circumstance. As Adler and Philippon note, even significantly higher capital requirements would be insufficient to ensure that financial institutions can be resolved. They argue that the simplest solution is to have a temporary government funding backstop that acts much as “debtor-in-possession” (DIP) funding works in ordinary bankruptcy procedures.

DIP financing is often an essential component of a corporate reorganization. It gives the bankruptcy judge authority to allow the restructured firm to borrow in a way that subordinates the claims of prior creditors. A DIP loan can increase the eventual recovery value for prior creditors by allowing the firm to keep operating and earn profits. But DIP loans are generally small: according to one recent analysis, aggregate commercial (non-government) DIP funding peaked in 2009 at $22.5 billion, and was roughly half that amount as of 2014.

The chart below shows 10 large DIP financings. The important thing to note is how small these are relative to the potential losses of a financial behemoth. Not only that, but the largest of these loans—to General Motors in 2009—was funded by the governments of the United States (using TARP funds) and Canada. While we are hardly DIP experts, the biggest reported commercial DIP loan that we came across in a limited online search was only $10 billion, a fraction of the $54-billion loss of market value relative to book when the Lehman bankruptcy began (see Kapur, page 188).

Large debtor-in-possession financings (Billions of dollars)

Note: Government finance in red; commercial finance in black. Sources: Various online reports (for example, here).

This mismatch between the availability of private DIP funding and the potential losses of a financial behemoth seriously understates the case for temporary government funding to make resolution credible. In a financial crisis, not just one, but several systemic intermediaries may require speedy resolution at the same time. Precisely at such a juncture, private DIP funding is likely to shrivel: the usual lenders are either themselves systemic or (like leveraged hedge funds) dependent for their own funding on systemic intermediaries.

Temporary government DIP funding is, in effect, a form of catastrophe insurance if a crisis wipes out both the equity capital and the long-term unsecured debt of one or more LCFIs. Limiting the catastrophe insurance—and the resulting moral hazard—requires that we impose strict self-insurance requirements on LCFIs (in the form of high equity capital and TLAC thresholds). This constitutes private investors’ and counterparties’ “deductibles” in a crisis. As catastrophe insurance, government DIP funding is analogous to the central bank’s role as lender of last resort and the government’s role as deposit insurer. In neither case would a private group have sufficient resources in crisis circumstances. So, unless we limit the size of intermediaries, the government is an essential part of any resolution mechanism that may require DIP funds.

While President Trump’s ordered review highlights the loss of market discipline from the availability of public funding, some forms of moral hazard are simply unavoidable. For example, the lack of a credible resolution scheme also creates moral hazard: namely, the likelihood that a future government facing a crisis will enact a bailout just as the U.S. government did with TARP in 2008. Accordingly, we view regulation (particularly higher capital requirements) and supervision as the tools needed to overcome the moral hazard from OLF. Like the central bank and the deposit insurance fund, the OLF itself is an essential part of any policy framework intent on delivering financial stability.

The other difference between Chapter 14 and OLA lies in the attitude of foreign regulators. The danger is that, without confidence in the U.S. resolution process, and without the cooperation of an authorized U.S. regulator, they may prefer to ring-fence assets in their jurisdictions (see, for example, Carmassi and Herring). In 2010, the Bank of England and the FDIC approved a memorandum of understanding designed to build mutual confidence about resolution and to limit the incentive to seize assets locally that would otherwise facilitate a fair and orderly global resolution. The loss of such trust and cooperation could result in a race among regulators to grab assets that undermines efficient capital planning and eventual reorganization, precisely the opposite of what a credible bankruptcy procedure aims to achieve.

So, it should come as no surprise that—as the quotes at the start of this post suggest—foreign regulators want reassurance that the evolving U.S. resolution scheme will be a credible one. From our perspective, by raising the odds of an effective resolution, FIBA (as a complement to Dodd-Frank) boosts the credibility of the U.S. regime. Over time, foreign regulators also may be reassured that the Chapter 14 mechanism is similar to the FDIC’s SPOE strategy, which they have welcomed. In both cases, the regime’s credibility depends on the presence of living wills and adequate loss-absorbing capital.

Ultimately, however, neither investors nor foreign regulators will be confident in a resolution regime that lacks an OLF-like provision for temporary government funding. In its absence, they will expect a future U.S. government to re-introduce an ad hoc bailout mechanism when it is inevitably needed. As a result, eliminating the OLF would neither limit too-big-to-fail nor prevent the excessive risk taking that it feeds.