Eclipsing LIBOR

“…the volume of unsecured wholesale lending has declined markedly…. This development makes LIBOR more susceptible to manipulation, and poses the risk that it may not be possible to publish the benchmark on an ongoing basis if transactions decline further.” FSOC 2016 Annual Report, page 5.

The manipulation of the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) began more than a decade ago. Employees of leading global firms submitted false reports to the British Banking Association (BBA), first to influence the value of LIBOR-linked derivatives, and later (during the financial crisis) to conceal the deterioration of their employers’ creditworthiness. U.S. and European regulators reported many of the details in 2012 when they fined Barclays, the first of a dozen financial firms that collectively paid fines exceeding $9 billion (see here). In addition to settling claims of aggrieved clients, these firms face enduring reputational damage: in some cases, management was forced out; in others, individuals received jail terms for their wrongdoing.

You might think that in light of this costly scandal, and the resulting challenges in maintaining LIBOR, market participants and regulators would have quickly replaced LIBOR with a sustainable short-term interest rate benchmark that had little risk of manipulation. You’d be wrong: the current administrator (ICE Benchmark Administration), which replaced the BBA in 2014, estimates that this guide (now called ICE LIBOR) continues to serve as the reference interest rate for “an estimated $350 trillion of outstanding contracts in maturities ranging from overnight to more than 30 years [our emphasis].” In short, LIBOR is still the world’s leading benchmark for short-term interest rates.

Against this background, U.K. Financial Conduct Authority CEO Andrew Bailey recently called for a transition away from LIBOR before 2022 (see here). In this post, we briefly explain LIBOR’s role, why it remains an undesirable and unsustainable interest rate benchmark, and why it will be so difficult to replace (even gradually over several years) without risking disruption.

As articulated by Duffie and Stein, the basic rationale for financial benchmarks, ranging from the S&P 500 to the Brent oil price, is three-fold. First, they lower transaction costs by providing an agreed basis for settling trades. Second, by focusing trades on a particular instrument, benchmarks foster competition and improve market depth. While competition squeezes per-trade margins, the transparency provided by a benchmark can boost market activity sufficiently to compensate the traders receiving smaller margins. This explains why private coordination efforts have led to benchmarks in the past: BBA LIBOR, which arose in the 1980s, is just such a case (for a brief history, see Hou and Skeie). Third, benchmark-linked assets provide a mechanism for hedging common risks, increasing the overall risk-bearing capacity of the financial system.

So, what’s the problem with LIBOR? Unfortunately, unlike the S&P 500 index or the Brent oil standard, LIBOR is not based on transactions. In its pre-2014 incarnation, the BBA calculated LIBOR from a survey of a panel of large London banks who were asked every business day at 11:00am to estimate their cost of uncollateralized borrowing in a specific currency at a specific maturity. In the case of dollar LIBOR, for example, the 2005 panel included 16 banks, and the BBA reported a trimmed mean measure that dropped the top 2 and bottom 2 submissions (for details of the process, see Eisl et al). Overall, the BBA reported 150 LIBOR benchmarks each day, covering 10 currencies at 15 maturities ranging from overnight to 12 months.

To reduce the risk of manipulation, ICE has implemented a number of useful reforms since 2014. These include: (1) promoting the use of transactions data in banks’ estimates; (2) including loans from corporates as well as banks to broaden the transactions basis; (3) shrinking the number of currencies from 10 to 5 and maturities from 15 to 7 to eliminate those currency-maturity pairs where very few transactions occur; (4) establishing a detailed code of conduct to emphasize the importance of integrity ; (5) delaying publication of individual bank submissions to reduce the opportunity of gaming by banks that know the full distribution of submissions, in addition to their own; and (6) implementing a range of statistical checks on the validity of bank submissions.

Despite all these worthy improvements, the paucity of transactions at some currency-maturity pairs makes it impossible for participating banks to escape the need for expert judgment in making their daily submissions. As of the second quarter of 2017, ICE reported that only a bit more than one third of submissions for U.S. dollar three-month LIBOR—the most important tenor for derivatives markets—was based on transactions. To put it simply, wherever submissions rely on expert judgment, rather than transactions, there is the potential for manipulation.

The persistent decline in uncollateralized short-term borrowing across relevant maturities, and the associated reduction in the number of transactions, is only making matters worse (see the opening quote from U.S. Financial Stability Oversight Council). As an example of the broad trend, we can compare unsecured and secured (collateralized) short-term funding in the euro area. The following two charts plot the trajectory of these two types of funding using data from the ECB’s money market survey. Over the past dozen years, secured borrowing has gradually replaced unsecured lending. As the first chart shows, from 2003 to 2015, the latest available data, unsecured funding plunged by roughly 85 percent. Simultaneously, secured funding grew by nearly 90 percent (see the second chart). The two charts also highlight the relative scarcity of transactions longer than one month in maturity.

Euro money market: Cumulative quarterly turnover in unsecured cash borrowing (2003=100), 2003-2015

Source: Adapted from Chart 16, ECB Euro money market survey 2015.

Euro money market: Cumulative quarterly turnover in secured cash borrowing (2003=100), 2003-2015

Source: Adapted from Chart 30, ECB Euro money market survey 2015.

It is important to keep in mind that even a purely transactions-based benchmark will fail when there are only a few transactions. The reason is that it, too, can be manipulated with a few small, well-timed trades.

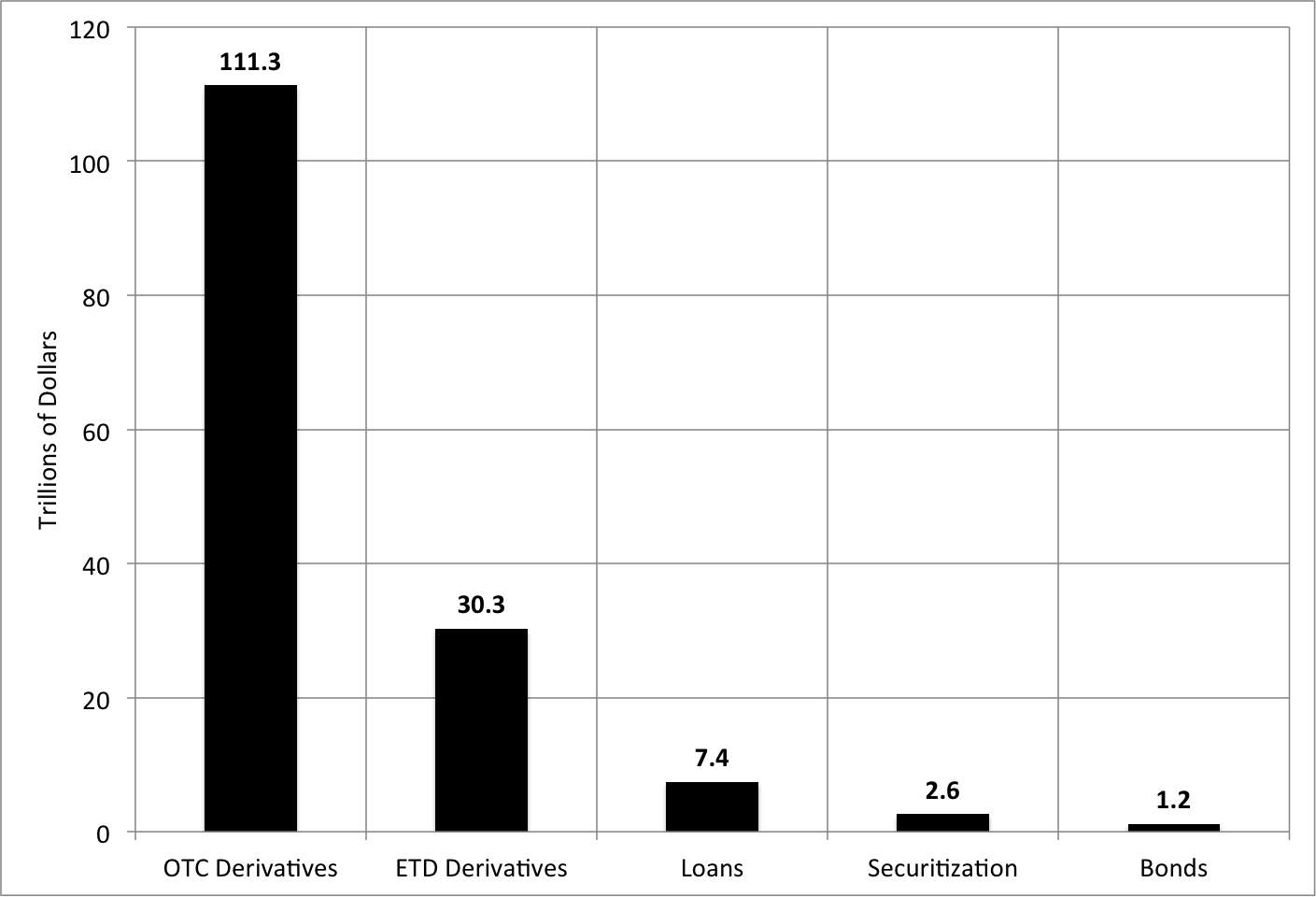

To give some sense of the scale of the problem, we turn again to Duffie and Stein. They report that daily transactions at the key three-month maturity in LIBOR-based U.S. dollar derivatives markets are roughly 1,000 times larger than in the cash market for unsecured bank funding. Furthermore, the stock of derivatives that are affected by price movements is about 100,000 times larger, creating the possibility for enormous derivatives-market gains or losses in response to tiny changes in LIBOR. Under such conditions, the temptation for manipulation can be overwhelming, even in the face of strong compliance oversight. Furthermore, many of these LIBOR-linked derivatives probably are being used to hedge general (default-risk-free) interest rate risk, rather than the bank funding risk premium, which is an important and variable component of LIBOR, on top of the risk-free component. To highlight this point, the following chart shows that the estimated volume of U.S. dollar LIBOR-linked derivatives is more than 12 times that of LIBOR-linked debt instruments that creditors may wish to hedge.

Estimated volume of U.S. Dollar LIBOR-linked derivatives and debt instruments (Trillions of U.S. dollars)

Notes: OTC over the counter. ETD Exchange-traded. Source: Based on Figure 1, page 243, Final Report of the Market Participants Group on Reforming Interest Rate Benchmarks, 2014, and authors’ calculations.

Faced with an environment where there are few unsecured transactions, willingness to participate in the survey panels is eroding. From the banks’ perspective, participating in the LIBOR survey (or in surveys for Euribor, HIBOR, SIBOR and other IBORs) is costly (reflecting the increased compliance obligations) and poses large legal and reputational risks. Those risks only grow as the submissions rely increasingly on expert judgment. Unsurprisingly, the Euribor panel has shrunk from a peak of 44 institutions five years ago to only 20 today. Banks also have exited from other panels, such as those in Hong Kong (HIBOR) and Singapore (SIBOR).

The fact is that LIBOR is on life support. To keep it alive, the U.K. authorities have had to cajole leading banks to remain “voluntary” participants (see, for example, here). In his July speech, the FCA’s Bailey explained that his agency’s leadership has “spent a lot of time persuading panel banks to continue submitting” to avoid “the market disruption that would be caused by an unexpected and unplanned disappearance of LIBOR.” Bailey also warned that—under the new European Benchmarks Regulation that takes effect on January 1, 2018—the FCA’s authority to compel banks to make LIBOR submissions will expire before the currently planned 4- to 5-year transition away from LIBOR is complete.

Fortunately, a range of international regulators are hard at work to make the transition as smooth and rapid as possible. In the United States, in 2014 the Federal Reserve convened the Alternative Reference Rates Committee (ARRC), a group of market participants who have been assessing transactions-based alternatives to LIBOR. In June 2017, the ARRC selected as its best-practice short-term interest rate benchmark a new “broad Treasuries repo financing rate”—to be published by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (FRBNY) in cooperation with the Treasury Office of Financial Research (OFR). And, on August 24, the Federal Reserve Board sought public comment on the proposal to produce this new Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) and two other narrower measures of secured financing costs.

SOFR has four key benefits relative to LIBOR. First, it will be based on a deep, liquid market, with average daily transactions of several hundred billion dollars, making it difficult to manipulate. Second, it will be calculated as a volume-weighted median (rather than a trimmed mean), making it less prone to bias (see Eisl et al). Third, as a secured financing rate, it is more consistent with post-crisis short-term financing practice. And fourth, as a near-default-free rate, it will provide many investors who currently use LIBOR-linked derivatives to hedge default-free interest rate risk with a better mechanism for doing so.

That said, SOFR lacks two elements that have been integral to LIBOR: (1) a range of maturities; and (2) the funding risk premium of banks. With regard to the first, given that there are other derivatives—namely, for Treasury bills, notes and bonds—that allow investors to manage maturity risk, this seems like a secondary issue. The loss of LIBOR-linked derivatives would, however, pose a much bigger challenge for creditors wishing to manage fluctuations in risks associated with bank (or banking system) borrowing—what is normally referred to as “funding risk.”

Put differently, it would be useful to have two benchmarks—one like SOFR to hedge changes in risk-free rates; and one that is tailored to hedging changes in the level of bank funding risk. The Financial Stability Board’s (FSB) Market Participants Group (MPG) proposal for an exclusively transactions-based LIBOR+ seems well-suited to this second purpose. To ensure an adequate volume of transactions, LIBOR+ would be based on all available wholesale unsecured bank funding rates (including bank commercial paper and certificates of deposit) at the relevant maturity. (See the MPG’s final report—section 2.2.1—which responded to the FSB’s mandate to identify alternative reference rates and identify a viable transition).

What if everyone started immediately using SOFR, rather than LIBOR, for both debt and derivatives contracts? How quickly would the legacy LIBOR-linked contracts disappear? In some markets, such as exchange-traded derivatives, it would probably take less than 5 years (see Figure 2, page 244, here). However, many over-the-counter derivatives probably will linger for longer. And, some LIBOR-based debt instruments—like the 30-year mortgages included in mortgage-backed securities—have especially long lives, so they could be with us for decades. Finally, without authorities stepping in, it is doubtful that all market participants will shift instantly to using SOFR-linked financial instruments on their own, even if it is in their collective interest to do so. With LIBOR’s end now on the horizon, regulators should at least require that all new LIBOR-linked contracts include a fallback clause to facilitate the substitution of a sustainable reference rate if LIBOR is no longer available or is deemed unreliable by regulators.

What would happen to legacy LIBOR instruments if LIBOR were to disappear? In the absence of specific legal provisos, courts would have to resolve such contract frustration. Is it possible to limit these legal risks by introducing a comparable, but sustainable replacement rate? At short maturities where it deemed transactions sufficient, the MPG expressed confidence that LIBOR+ could be used to achieve a “seamless transition.” However, it is uncertain how much legal risk would linger or what would happen if the volume of uncollateralized funding continued to shrivel. Presumably, contract holders facing losses from a benchmark substitution would challenge its validity in court, leaving the potential for market disruption.

The good news is that the international regulators and leading market participants—including the largest banks that dominate the derivatives markets—are keenly aware of the risks arising from the need to replace LIBOR. And, with helpful coordination, they have embarked on a path to develop, test and agree on practical substitutes. While there is no way to guarantee a disruption-free transition, the partial eclipse of LIBOR already is well underway. It is only a matter of time until we reach totality.