An Open Letter to Randal K. Quarles, Federal Reserve Vice Chair for Supervision

Sunday, June 21, 2020

Dear Vice Chair Quarles,

Nearly three years ago, we wrote an open letter congratulating you on your nomination as the first Vice Chair for Supervision on the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. In that letter, we highlight the central mission of ensuring the resilience and promoting the dynamism of the U.S. financial system.

Today we write to express our profound disappointment regarding the plans (expressed in your June 19 speech on “The Adaptability of Stress Testing“) to limit the disclosure of this year’s large-bank stress tests. In our view, failure to publish the individual bank results from the special COVID-19 related “sensitivity analysis” weakens the credibility and effectiveness of the Fed’s stress testing regime.

Consequently, we urge you to reverse course and to announce this week the individual bank sensitivity results, along with the aggregates. To put it bluntly, the point of a supervisory stress test is disclosure. Anything short of full transparency leaves potentially destabilizing questions unanswered.

Let us start by highlighting the three key elements of an effective stress testing regime that have characterized the Fed’s stress tests since the extraordinary 2009 Supervisory Capital Assessment Program (SCAP). These are severity, flexibility, and transparency.

If stress test scenarios are insufficiently dire, there is no point. For example, in the scenarios applied to the U.S. government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) prior to 2007, house prices typically rose for the first 10 quarters, before falling only modestly over the full 8-year horizon. Similarly, as Goldstein notes, persistent doubts about the severity of European bank stress tests (at least prior to the 2014 comprehensive assessment) limited their credibility (see also Acharya and Steffen).

Second, effective tests must include scenarios that adapt—sometimes rapidly—to changing economic and financial conditions. This was a key strength of the SCAP. Designed and implemented in early 2009, at the depth of the Great Financial Crisis, in short order the SCAP provided a credible assessment of the capital needs of the largest U.S. banks under extremely adverse conditions.

Third, scenarios should be transparent after the fact, not before. For a stress test to be effective, banks must fix their balance sheets before supervisors reveal the scenarios. Tests that everyone can anticipate in detail and react to in advance are not tests. On this basis, too, the pre-2007 GSE tests fell disastrously short: while the GSEs always passed the tests, they collapsed in the crisis.

Critically, to promote confidence and effective market function in the presence of a large shock, supervisors must disclose results regarding individual institutions. Aggregates are insufficient. Failure to disaggregate the results fosters doubts about the presence of weak banks and can lead to runs or—when creditors cannot easily distinguish between strong and weak banks—to a general panic.

The May 2009 SCAP, with its bank-by-bank detail, highlights the favorable impact of full disclosure. Following publication, the largest U.S. banks were again able to tap the equity market to help them lend to healthy borrowers. Because the SCAP played such a critical role in ending the Great Financial Crisis, many observers (including ourselves) view it as the most successful stress test in history (see our earlier post).

In light of the importance of severity and flexibility in stress test scenarios, we found heartening the Fed’s May announcement of its intention to supplement the scenarios announced in February with a COVID-related sensitivity analysis. Based solely on economic indicators, we already knew that the impact of COVID was significantly worse than the severely adverse scenario provided in February (see following table). Post COVID, ensuring confidence in the banks requires that we have some sense of both their current state and of their ability to withstand further deterioration in general economic conditions.

Comparing the Fed’s severely adverse scenario to current conditions

Notes: The economic estimates treat the second quarter of 2020 as the trough of the recession and the peak of the unemployment rate. The second-quarter 2020 estimates for the financial indicators reflect the averages through June 19, with the exception of the stock market index (latest observation) and the VIX (maximum daily close during the quarter). Sources: Federal Reserve for the scenario; FRED and author’s calculations for the current estimates.

For this reason, we suspect that analysts of the Fed’s June 25 stress test report will heavily discount the results from the severely adverse scenario, while paying close attention to the three “downside risk paths” that comprise COVID-related sensitivity analysis. To be sure, following the extraordinary actions of U.S. monetary and fiscal authorities, recent financial market developments generally are more favorable than those in the severely adverse scenario. However, the COVID-customized sensitivity methodology mirrors the flexible-and-severe SCAP approach that had such a positive impact on investor (and public) confidence in the largest U.S. banks in mid-2009.

The lesson from this history is that the current environment—in which the COVID shock likely imposed significant damage on bank capital positions—is precisely when disclosure of individual bank stress test results is vital to foster confidence in the banking system. Because it is forward looking, and is available on a high-frequency basis, we find the NYU Stern Volatility Lab’s market-based measure of a bank’s capital shortfall—known as SRISK—a particularly useful indicator of perceived capital adequacy. As of June 19, as investors anticipate the hit from COVID, U.S. intermediaries’ aggregate SRISK—at nearly $800 billion—remains close to the peaks observed in the financial crisis of 2007-09, having surpassed that level temporarily in May (see following chart).

SRISK (Billions of U.S. dollars), 2007-June 19, 2020

Note: Data history provided by NYU Stern Volatility Lab. The monthly observations since end-March are based on the Volatility Lab website and authors’ calculations. The data use the global dynamic MES model of world financials with default assumptions (namely, 40 percent global equity drop; 40 percent of “separate accounts” of insurers included; and capital requirements of 8 percent).

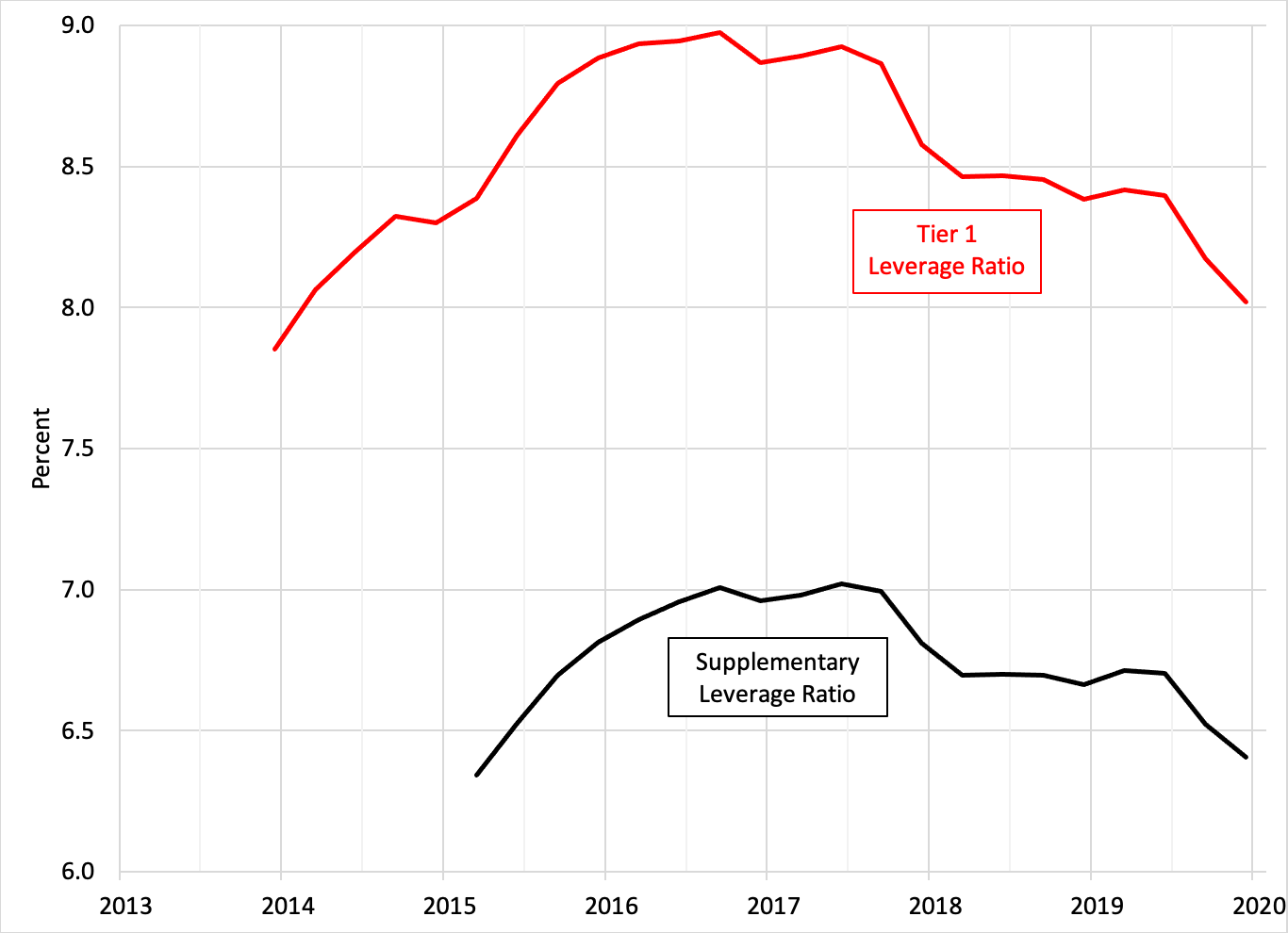

Moreover, as we have warned before, the Federal Reserve in recent years unwisely permitted the largest U.S. banks to make shareholder payouts (summing dividends and share buybacks) in excess of their earnings. As a result, in the final years of the decade-long cyclical expansion, when banks should have been building their capital buffers to improve resilience, supervisors tolerated a persistent decline in the regulatory leverage ratios of the largest U.S. banks (see next chart).

U.S. global systemically important banks (G-SIBs) regulatory leverage ratios, Dec 2013-Dec 2019

Note: While both ratios use Tier 1 capital in the numerator, the denominator of the supplementary leverage ratio is a broader measure that includes not just balance sheet assets but also derivatives exposure and commitments. Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City semi-annual Bank Capital Analysis.

Finally, while current financial conditions are better than in the severely adverse scenario, banks still face a flat yield curve—especially by comparison to past (far milder) recessions—combined with an uncertain recovery that is likely to include rising defaults by firms and households. Consequently, profit prospects over the next year offer little hope of replenishing bank capital soon (see, for example, the Federal Reserve May 2020 Financial Stability Report, page 42).

Against this worrisome background, and in light of the Fed’s successful 2009 SCAP approach, we naturally expected that the Fed would publish individual results from the three “downside risk paths” in the COVID-19 sensitivity analysis. Indeed, if U.S. large banks remain sufficiently well capitalized to weather the COVID storm without public support, then the Federal Reserve has a powerful incentive to publish the full results. Doing so will clear the air, putting to rest concerns that following the COVID shock one or more big banks may no longer be able to help supply credit to healthy borrowers.

Conversely, providing only an aggregate result will invite the unfortunate question of what information supervisors wish to conceal. Since it will be natural to wonder whether one or more banks are in trouble, the Fed’s lack of transparency could unintentionally increase stress in the system.

Moreover, it is difficult to see how the Fed’s effort to limit disclosure will prove anything but futile. The uncertainty about individual banks will encourage the healthiest institutions to disclose their full sensitivity results as soon as possible. And, as you note (in footnote 2), securities law may oblige other banks to report theirs, too.

In our view, there are two things that you and your colleagues can do immediately to enhance financial stability at this precarious time. First, release a complete and timely set of individual banks’ test results. Second, following the recommendation of numerous policymakers elsewhere in the world (see here and here), issue a temporary rule prohibiting all the stress test banks from any voluntary pay-outs (including dividends, bonuses and share repurchases).

A rule restricting payouts for the time being would help the weakest players build resiliency while limiting the stigma associated with any individual institution’s actions. Considering the risks ahead, and in light of the strength of the equity market compared to the severely adverse scenario, calling on all the banks now to issue more equity (as Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis President Kashkari has done) could prove even more effective.

The bottom line: we hope that the Federal Reserve will immediately alter plans for the announced June 25 disclosure and include full bank-by-bank results for the sensitivity analysis with the outcomes for the traditional stress tests.