Open-end Funds vs. ETFs: Lessons from the COVID Stress Test

“These funds are built on a lie, which is that you can have daily liquidity for assets that fundamentally aren’t liquid. And that leads to an expectation of individuals that it’s not that different from having money in a bank.” Mark Carney, then-Governor of the Bank of England, Speaking to the House of Commons Treasury Committee, June 26, 2019.

COVID-19 posed the most severe stress test for financial markets and institutions since the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2007-09. By some measures, the COVID shock’s peak impact was larger than that of the GFC—both the VIX rose higher and intermediaries’ estimated capital shortfalls were bigger. As a result, the COVID experience provides a natural laboratory for testing the resilience of many parts of the post-GFC financial system.

For example, the March 2020 dysfunction in the corporate bond market highlights the extraordinary fragility of a market that accounts for nearly 60% of the debt and borrowings of the nonfinancial corporate sector. Yield spreads over equivalent Treasuries widened further than at any time since the GFC, with bond prices plunging even for instruments that have little risk of default. (See Liang for an excellent overview.)

You might think that the COVID shock would reveal fragilities through both a reduction in the perceived creditworthiness of borrowers (reflecting a decline of expected future cash flows) and an increase in required compensation for risk (say, due to a heightened correlation with consumption risks). Indeed, as the full force of the pandemic hit in March, it did prompt a wave of credit downgrades.

Yet, scholarly work suggests that the predominant sources of fragility were elsewhere. For example, dealers were reluctant to increase inventories while deep-pocketed market participants generally failed to step in. As a result, the cost of trading corporate bonds surged. It took the announcement of the Fed’s willingness to intervene as a “market maker of last resort” to bring the market back to life. (See, for example, the discussions in Haddad, Moreira and Muir, O’Hara and Zhou, and Kargar et al.)

In this post, we focus on how, because of the contractual agreement with their shareholders, an extraordinary wave of redemptions created selling pressure on corporate bond mutual funds that almost surely exacerbated the liquidity crisis in the corporate bond market. To foreshadow our conclusions, we urge policymakers to find ways to reduce the gap between the illiquidity of the assets held by corporate bond (and some other) mutual funds and the redemption-on-demand that these funds provide. To reduce systemic fragility, we also urge them—as we did several years ago—to consider encouraging conversion of mutual funds holding illiquid assets into ETFs, which suffered relatively less in the COVID crisis.

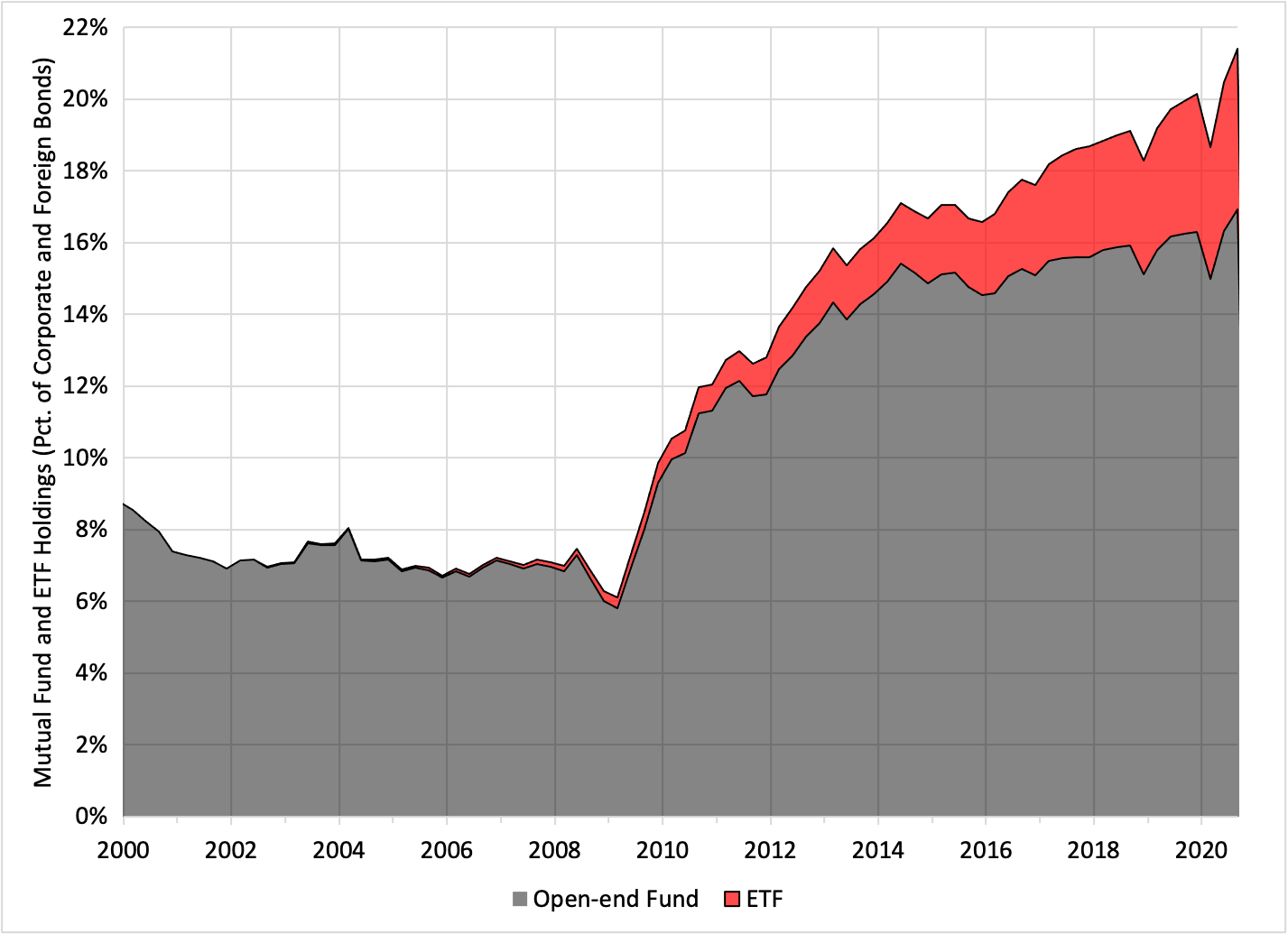

Why should we care about mutual funds and ETFs that hold corporate bonds? One obvious reason is scale. As the following chart shows, the share of corporate and foreign bonds held by mutual funds and ETFs has surged since the GFC, with the portion held by ETFs growing particularly rapidly. Collectively, these funds now hold 21.4 percent of the total quantity outstanding, a share that is only slightly smaller than the 22.8 percent held by insurers, who are the traditional holders of corporate bonds. Along the current trajectory, it would be surprising if mutual funds and ETFs do not soon become the largest holders of corporate and foreign bonds.

Share of corporate and foreign bonds held by mutual funds and ETFs (Percent), 1980-Sep 2020

Source: Tables L.122 and L.213, Financial Accounts of the United States (Federal Reserve Z.1)

The second reason is the history of bond fund fragility that has the potential to undermine the provision of credit to healthy borrowers. Put differently, runs on open-end mutual funds with floating net asset values (NAVs) are not new. As the opening citation from former Bank of England Governor Mark Carney suggests, an open-end fund is vulnerable whenever its assets are less liquid than its liabilities (the promise to redeem each day at NAV). This is surely true for mutual funds holding corporate bonds, which are illiquid even in normal times, and especially so in stress periods (see here). More generally, whenever the illiquid asset prices face downward pressure, investors in open-ended funds have an incentive to run, leaving slower-moving investors to bear the costs of the resulting fire sales.

The academic literature has emphasized this vulnerability for at least a decade. In 2010, Chen, Goldstein and Jiang documented the sensitivity of funds holding illiquid assets to bad past performance. Analyzing the summer 2013 bond market Taper Tantrum—in which bond yields soared following the Fed Chair’s remarks about tapering asset purchases—Feroli, Kashyap, Schoenholtz, and Shin detected destabilizing feedback loops between returns and flows for funds holding corporate or emerging market bonds, but not for Treasury funds. In 2017, Goldstein, Jiang and Ng highlighted the potential for first-mover advantage and fragility in corporate bond funds.

To date, the COVID shock presents the most powerful test of these systemic concerns. Using daily fund flow data since 2010 for the Morningstar universe of corporate bond mutual funds and ETFs, Falato, Goldstein, and Hortaçsu calculate that the cumulative outflows in February-March 2020 reached 9% of NAV for the average fund, more than four times higher than at the peak of the June 2013 Taper Tantrum. Similarly, the share of funds experiencing “extreme” outflows (in the bottom decile of the distribution) over multiple days reached a record. Falato et al. also find that, across the array of corporate bond funds (and ETFs), the illiquidity of fund assets and the vulnerability to fire sales are important drivers of redemptions (and sales).

The following chart provides some indication of the extraordinary size of the outflows during in the COVID panic. The monthly net flows are shown as a percent of the average fund/ETF holdings of corporate and foreign bonds during the period from 2018 through the third quarter of 2020. For investment-grade funds (black) and ETFs (red) the March flows are 4.4 and 3.1 standard deviations below the full-period mean. As large as that is, it almost certainly understates the impact in the first weeks of March before the Fed’s extraordinary interventions began to reverse the outflows in the latter part of that month.

Investment-grade bond mutual fund and taxable bond ETF monthly net flows (Percent of average corporate and foreign bonds held by these funds since 2018), 2018-Nov 2020

Sources: ICI (estimated long-term mutual fund flows and ETF net issuance) and Table L.213, Financial Accounts of the United States (Federal Reserve Z.1)

For our current purpose, one of the most interesting aspects of the COVID bond market shock is the differential impact on mutual funds and ETFs. Whether mutual funds or ETFs are more resilient in a crisis is at least partly an empirical issue. For example, Bhattacharya and O’Hara highlight speculative herding in ETFs as a potential source of systemic risk. And, in the period from 2010 to 2018, Dannhauser and Hosenzaide find that corporate bond ETFs attract investors with a relatively high demand for liquidity, adding to their fragility in general and contributing to the selloff in the Taper Tantrum. Finally, even in an illiquid market, ETF issuers may still wish to rebalance their portfolios to track an index.

Yet, analysis of the COVID shock strongly suggests that mutual funds are the greater source of systemic risk. In an earlier post, we argued that ETFs should be less fragile than open-end mutual funds because (like closed-end funds) they do not offer redemption on demand to most holders, limiting the incentive to run. Moreover, when markets seize, the ability of “authorized participants” to arbitrage between the prices of ETFs and their underlying assets is severely diminished. Consequently, in a crisis, ETFs exhibit large and persistent deviations from NAV, while open-end mutual funds must redeem each day at NAV, creating a hefty risk of fire sales.

Falato, Goldstein and Hortaçsu directly compare the impact of the COVID shock on corporate bond ETFs and a set of mutual funds matched for performance, size and age. They find that the ETFs exhibit smaller outflows than mutual funds (see their Table 7, Panel B). ETFs also are substantially less likely to experience large or persistent outflows. The conclusion: “ETFs were more resilient than open-end funds in the crisis.”

So, what are the lessons from the COVID episode? There is little dispute that the Fed’s engagement as market maker of last resort was highly effective, without much direct impact on the Fed’s balance sheet. Yet, this new central bank role threatens to undermine market discipline by providing a permanent liquidity backstop for illiquid assets.

One approach to limiting the asset price distortions from anticipated Fed intervention is to make the underlying assets more liquid. For example, market participants could shift from the current dealer market for corporate bonds to one in which all market participants can more easily supply liquidity (as in “all-to-all” trading, where non-dealers also can respond to trade inquiries on a shared platform). However, the COVID experience suggests that non-dealer market participants did little to substitute for the constrained liquidity supply from dealers.

In our view, policymakers will need to find ways to make mutual funds holding illiquid assets more resilient. As then-Governor Carney explained to the Commons Treasury Committee in 2019, “something that better aligns the redemption terms with the actual liquidity of the underlying investment is infinitely preferable to the situation that we have today.”

The standard remedy (suggested by Falato, Goldstein and Hortaçsu; Liang; and BlackRock), is through a process known as swing pricing in which the fund NAV can change substantially to impose trading costs on those that purchase and redeem shares. In their study of U.K. corporate bond funds, Jin, Kacperczyk, Kahraman, and Suntheim (2019) conclude that swing pricing reduces first-mover advantage. Since November 2018, U.S. funds have had the option to impose swing pricing, but practical obstacles have hindered adoption (see, for example, here).

In addition to facilitating the use of swing pricing, policymakers also should enhance oversight over liquidity risk management by mutual funds. For example, policymakers may wish to require disclosure of standardized liquidity stress tests so that investors can compare the illiquidity risks across funds.

Finally, we return to our earlier proposal: encourage mutual funds holding illiquid assets to convert to ETFs. The COVID experience shows that a full substitution of ETFs for corporate bond mutual funds would not eliminate runs. However, just as with swing pricing and improved liquidity management, it should help reduce their scale and economic impact, making financial markets more resilient.

The bottom line: there is no single magic cure, so policymakers should use all the tools at their disposal to address the systemic risk posed by open-ended mutual funds that hold illiquid assets.