Fix Money Funds Now

“Free of capital constraints, official reserve requirements, and deposit insurance charges, these MMMFs are truly hidden in the shadows of banking markets. […] While generally conservatively managed, the funds are demonstrably vulnerable in troubled times to disturbing runs.” Former Federal Reserve Chair Paul Volcker, William Taylor Memorial Lecture, September 23, 2011.

On September 19, 2008, at the height of the financial crisis, the U.S. Treasury announced that it would guarantee the liabilities of money market mutual funds (MMMFs). And, the Federal Reserve created an emergency facility (“Asset-Backed Commercial Paper Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility”) to finance commercial banks’ purchases of illiquid MMMF assets. These policy actions halted the panic.

That episode drove home what we all knew: MMMFs are vulnerable to runs (see the citation from Chairman Volcker above). Everyone also knew that the Treasury and Fed bailout created enormous moral hazard. It is impossible for U.S. authorities to credibly promise not to repeat what they did in the autumn of 2008. These concerns motivated regulatory efforts to make MMMFs more resilient and less bank-like. But the resulting changes have proven to be half-hearted and, in some cases, counterproductive. As a result, the fragilities and the moral hazard persist.

Indeed, the COVID shock in March 2020 exposed that even MMMFs with floating net asset values (NAV) are vulnerable. So, to halt another run and to steady the critical short-term funding markets in which they operate, the Fed revived its 2008 emergency liquidity facilities. Not only that, but the Fed went further, relaxing capital and liquidity regulations to push commercial banks to help clean up the MMMF mess.

We hope the second time’s the charm, and that U.S. policymakers will now act decisively to prevent yet another panic that would force yet another MMMF bailout. In our view, two types of reforms would go a long way toward making the industry more resilient. The first is to confront head-on the fact that MMMFs (even with floating NAVs) are bank-line structures, and require them to finance themselves in part with subordinated liabilities that cannot be redeemed on demand. The second is to accept that, as their name implies, they are open-end mutual funds holding illiquid assets. As a result, regulators should require that they change their pricing mechanisms in a manner that compels investors seeking redemption of their shares to internalize the resulting fire sale costs.

Mutual fund companies offering MMMFs will surely protest, claiming that these types of reforms will limit the supply of short-term credit. This complaint almost surely lacks merit (see our earlier post). But even if they were correct, it is simply the cost of ensuring a safe financial system free from distortionary subsidies and repeated government bailouts. Indeed, considering recent concerns about the high and increasing levels of nonfinancial corporate debt (see, for example, the Fed’s Financial Stability Report, page 33), we view greater market discipline in the supply of credit as a feature (rather than a flaw) of any reforms to short-term money markets.

In this post, we briefly review key regulatory changes affecting MMMFs over the past decade and their impact during the March 2020 crisis. We then discuss the options for MMMF reform that the President’s Working Group on Financial Markets identifies in their recent report. Our conclusion is that only two or three of the report’s 10 options would materially add to MMMF resilience. The fact that everyone has known about these for years highlights the political challenge of enacting credible reforms.

How did we get here? The original source of MMMF vulnerability is that they are banks in all but name and legal form. MMMFs engage in liquidity, credit, and (to some extent) maturity transformation. Some of them still promise instant redemption of shares at a constant price of $1.00 on a first-come, first-served basis—regardless of the value of their assets. As in the case of a conventional bank, this creates a first-mover advantage that precipitates a run when investors believe conditions are deteriorating. As former Chairman Volcker put it (see citation above), such classic MMMFs offer bank deposits without capital requirements or deposit insurance.

In July 2014, prodded by the Financial Stability Oversight Council and nearly six full years after the financial crisis panic and bailout, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)—the regulator of MMMFs—partly addressed this issue. The new rules—announced to take effect up to two years later—compel prime institutional money funds (those non-retail funds that do not exclusively hold U.S. Treasury and federal agency debt) to adopt floating NAVs (rather than a constant dollar share value).

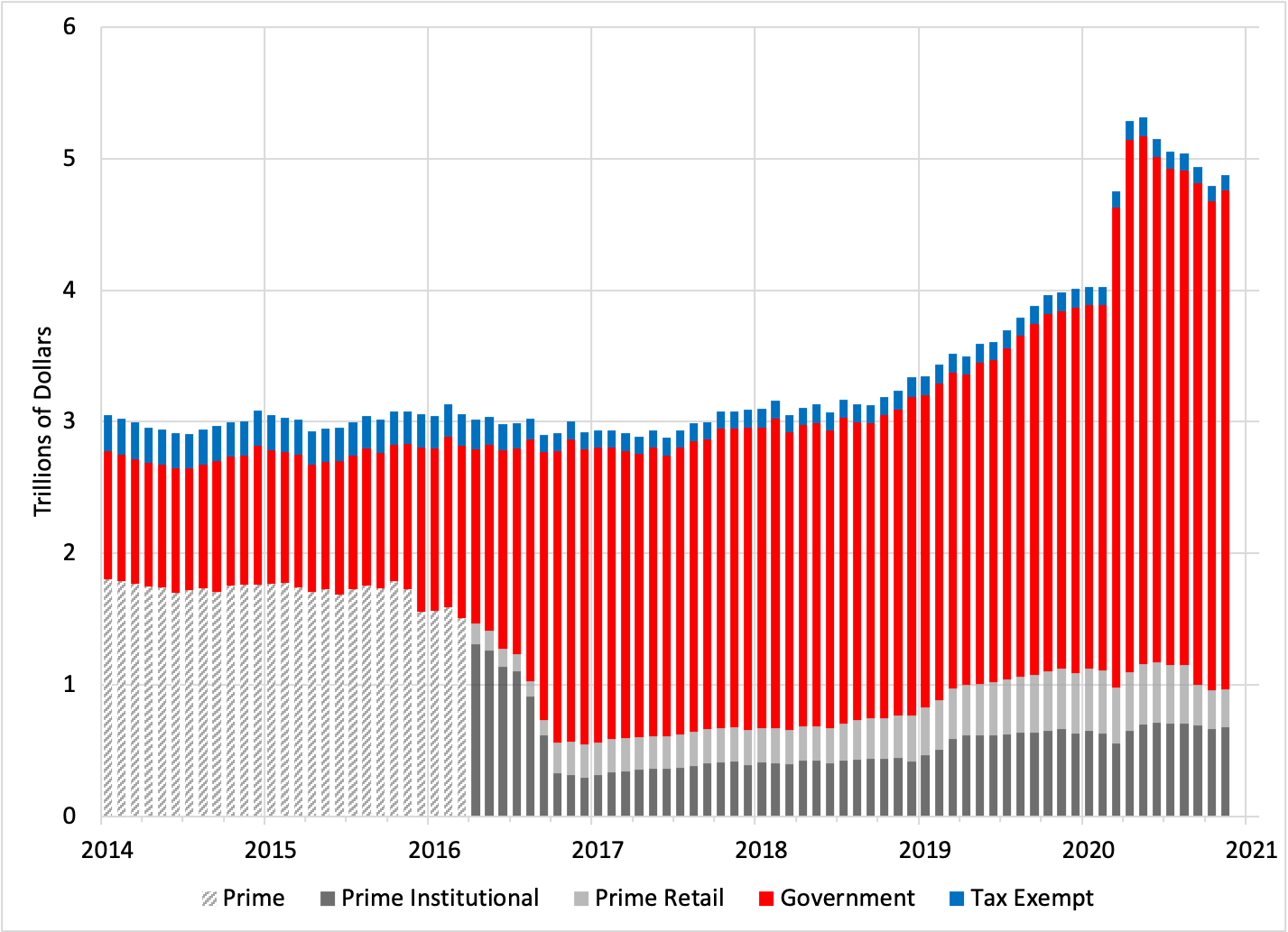

In anticipation, as the following chart reveals, institutional investors shifted massively to government-only funds that could maintain the fixed-value redemption scheme. Comparing the start of 2017 with mid-2014, overall MMMF assets rose slightly. But, those in prime funds plummeted by nearly $1.2 trillion, while government funds added a whopping $1.3 trillion. By early 2020, government funds accounted for 69 percent of total MMMF assets, more than double the share prior to the change. Despite these large shifts, there is little evidence of a decline in the overall supply of credit to private-sector borrowers (see our earlier post).

Money market mutual fund assets by fund type (Trillions of Dollars), Jan 2014-Nov 2020

Source: Treasury Office of Financial Research Money Market Fund Monitor.

The good news is that, by shifting its composition away from prime funds to government funds, these SEC rules did reduce the overall vulnerability of the MMMF sector. And, as the chart shows, even as prime funds (primarily institutional but also retail) experienced a run last March, inflows into government funds surged.

Unfortunately, this is not the end of the story. In 2014, the SEC also unwisely authorized the boards of prime institutional funds—using their discretion—to impose liquidity fees or temporarily suspend redemption once the fund’s “weekly liquid assets” (WLA) fell below the regulatory minimum of 30% of assets. (Published daily, WLA is a measure of funds that are readily accessible within seven days.) Even at the time, observers warned that redemption gates could foster, rather than diminish, first-mover advantage (see our earlier post). The reason is clear. Early warnings of trouble could prompt fund investors to run, draining a fund’s liquid assets. The resulting decline in WLAs—openly linked to potentially heightened liquidity fees and suspensions of redemption—could help coordinate a panic. As SEC Commissioner Kara Stein stated in July 2014: “I fear these incentives may result in a greater chance of fire sales during times of stress.” And, they did!

The COVID Shock and the Fed Response. The COVID shock hit a wide range of financial markets in March 2020. Equity volatility and spreads on 30-day AA nonfinancial commercial paper (CP) hit new highs, while high-yield corporate bond spreads spiked to levels not seen since 2009. And, as the SEC staff report on the COVID-19 shock noted (see page 5), both issuance and secondary trading froze in CP and certificates of deposit (CDs)—key instruments for prime institutional MMMFs.

Not surprisingly, investors in MMMFs that held privately-issued paper rushed for the exits. In the two weeks starting March 11, net redemptions from publicly-offered prime institutional funds approached $100 billion—about 30 percent of assets. Interestingly, as the following chart shows, the March 2020 run (measured as a share of initial assets) almost exactly mirrors the experience of prime institutional funds following the failure of Lehman in mid-September 2008. (As the SEC report notes, outflows from prime retail funds and tax-exempt funds during this period were notably smaller. See pages 25 and 27.)

Prime institutional fund assets (Indexed to 100 on March 6, 2020 and September 9, 2008)

Source: Li, Li, Machiavelli, and Zhou, Figure 2b, Liquidity Restrictions, Runs, and Central Bank Interventions: Evidence from Money Market Funds. Data kindly provided by Li et al.

To be sure, runs on open-end mutual funds (with floating NAVs) are neither new nor are they limited to MMMFs. A decade ago, Chen, Goldstein and Jiang documented the sensitivity of funds holding illiquid assets to bad past performance. Several years ago, Goldstein, Jiang and Ng highlighted the potential for first-mover advantage and fragility in corporate bond funds. And this year, Falato, Goldstein and Hortaçsu found large and sustained COVID-triggered outflows from corporate bond funds, in which both the illiquidity of each fund’s assets and its exposure to fire sales influenced the scale of hemorrhaging.

Yet, in the case of MMMFs, the SEC rules regarding liquidity fees and redemption gates almost surely amplified the COVID-triggered run on institutional prime funds. Recent research by Li, Li, Machiavelli, and Zhou provides compelling evidence that, in the COVID shock, funds with WLAs approaching the 30% threshold experienced accelerating outflows—something that did not happen in the 2008 episode that preceded the 2014 rule change. Industry assessments reinforce this observation. In July 2020, BlackRock wrote that “[t]he fear of the imposition of a liquidity fee or redemption gate essentially converted the 30% WLA threshold to a new ‘break the buck’ triggering event for investors.”

The good news, of course, is that the Fed’s massive interventions quickly turned the tide. In fact, as the chart above highlights, outflows from institutional funds halted virtually on the day that the Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility (MMMLF) began operation. Even so, the volume of the Fed's purchases—which peaked at a cumulative $53 billion on April 8—was substantial compared to the estimated scale of the runs on prime funds (about $130 billion).

Reform Proposals. The Fed’s success notwithstanding, U.S. regulators cannot and should not rely on central bank emergency operations to bail out MMMFs and stabilize critical short-term funding markets once a decade or so. So, how can we make this part of the financial system—including the MMMFs and the funding markets more broadly—far more resilient?

The December report of the President’s Working Group on Financial Markets lists 10 “reform” options. Unfortunately, most of these would do little to resolve the known flaws in the system. For example, decoupling the imposition of redemption gates from WLA thresholds would not eliminate the incentive for investors to run on funds holding illiquid assets. The same could be said for imposing floating NAVs on prime retail and tax-exempt funds. And, as history teaches us, the introduction of a private bank to mutualize the run risks on MMMFs is doomed to fail. In the end, the only organization capable of providing rapid and unlimited liquidity support in a crisis is the central bank, and it is the credible promise of such unlimited action that calms markets (as it did in March).

In our view, the three reforms with the greatest promise for making MMMFs resilient have been around for years. They are: (1) require capital buffers; (2) establish a minimum balance at risk (MBR) for investors; and (3) introduce swing pricing. As far as we can tell, these three tools are complementary.

On capital buffers, Hanson, Scharfstein and Sunderam (2015) estimate that a risk-weighted capital requirement of 3 to 4 percent on well-diversified MMMFs would substantially reduce the risk of runs. With respect to MBRs, McCabe, Cipriani, Holscher, and Martin (2013) consider delaying redemption (for, say, 30 days) on a fraction (perhaps 5 percent) of each investor’s funds. Moreover, those who redeem first would be at the head of the line to absorb fund losses. In effect, this is like making each fund investor a temporary holder of subordinated debt, with those who rush for the exit placed at the bottom of the stack. Finally, swing pricing passes on fund trading costs to those who purchase and redeem. In their study of U.K. corporate bond funds over a period including the 2007-09 financial crisis, Jin, Kacperczyk, Kahraman, and Suntheim (2019) conclude that swing pricing reduces the first-mover advantage. That said, it remains to be seen whether swing pricing could be calibrated to achieve the same effect in the MMMFs.

Bottom line: Fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me.

We are far beyond the point where government officials (like the President’s Working Group) should be satisfied with making yet another list of potential reforms and providing brief arguments on their pro’s and con’s. With the COVID crisis still fresh, U.S. policymakers need to move swiftly to forge a consensus for reforms that make MMMFs less vulnerable and prevent another crisis in the short-term funding markets.

For the most part, the policy failures of the past decade reflect a lack of political will, not a lack of comprehensive analysis. And, while we agree that the optimal policy approach would be holistic—addressing the fragility of the short-term funding markets generally—it would be foolish to let the best be the enemy of the good.

Indeed, there is no need to wait on making MMMFs far safer. Doing so will make short-term markets more resilient, too.

Acknowledgement: We thank authors Li, Li, Machiavelli, and Zhou for sharing the data that allowed to us to reproduce their Figure 2b.