Big Tech, Fintech, and the Future of Credit

“Microfinance is a positive development; it has clearly helped substantial numbers of poor people escape poverty… However, microfinance is not a substitute for institution building...” then-Federal Reserve Board Governor Frederic S. Mishkin, April 26, 2007.

Lenders want to know that borrowers will pay them back. That means assessing creditworthiness before making a loan and then monitoring borrowers to ensure timely payment in full. Lenders have three principal tools for raising the likelihood of that firms will repay. First, they look for borrowers with a sufficiently large personal stake in their enterprise. Second, they look for firms with collateral that lenders can seize in the event of a default. Third, they obtain information on the firm’s current balance sheet, its historical revenue and profits, experience with past loans, and the like.

Unfortunately, this conventional approach to overcoming the challenges of asymmetric information is less effective for new firms that have both very short credit histories and very little in the way of physical collateral. As a result, these potential borrowers have trouble obtaining funds through standard channels. This is one reason that governments subsidize small business lending, and why entrepreneurs are forced to pledge their homes as collateral.

Well, new solutions have emerged to overcome this old problem. In this post we discuss how technology is increasing small firms’ access to credit. By using massive amounts of data to improve credit assessments, as well as real-time information and platform advantages to enforce repayment terms, technology companies appear to be doing what traditional lenders have not: making loans to millions of small businesses at attractive rates and experiencing remarkably low default rates.

The biggest advances are in places where financial systems are not meeting social needs. In China, there are now alternatives where private bank credit was lacking. In Kenya, Ghana, and Indonesia, we are seeing leapfrogging, with technology companies supplying financial services in lieu of tradition providers. As for advanced economies—the United States, Japan, and Europe—tech firms have yet to make significant inroads. Whether they will depends on a host of factors, not least of which is how we choose to treat the ownership of the data that tech firms obtain and can exploit.

To understand changes in the delivery of financial services, we turn to some data recently collected by a group of researchers at the BIS led by Leonardo Gambacorta, in collaboration with the Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance (see here). Cornelli et al. provide information from 2013 to 2019 on credit supplied by what they label “fintech” and “big tech” firms in 100 countries. In their taxonomy, fintech firms are built around decentralized platforms that form the basis for peer-to-peer lending or the origination of loans for resale. While these firms have evolved over time, and now obtain more funding from institutional investors, their primary business remains provision of financial services. By contrast, for big tech firms, lending often represents only a small part of their business. Instead, these platform-based firms have many users with whom they have constant contact, and they can use the resulting information to screen potential borrowers. (In their paper, Cornelli et al. list 37 companies that they classify as big tech.)

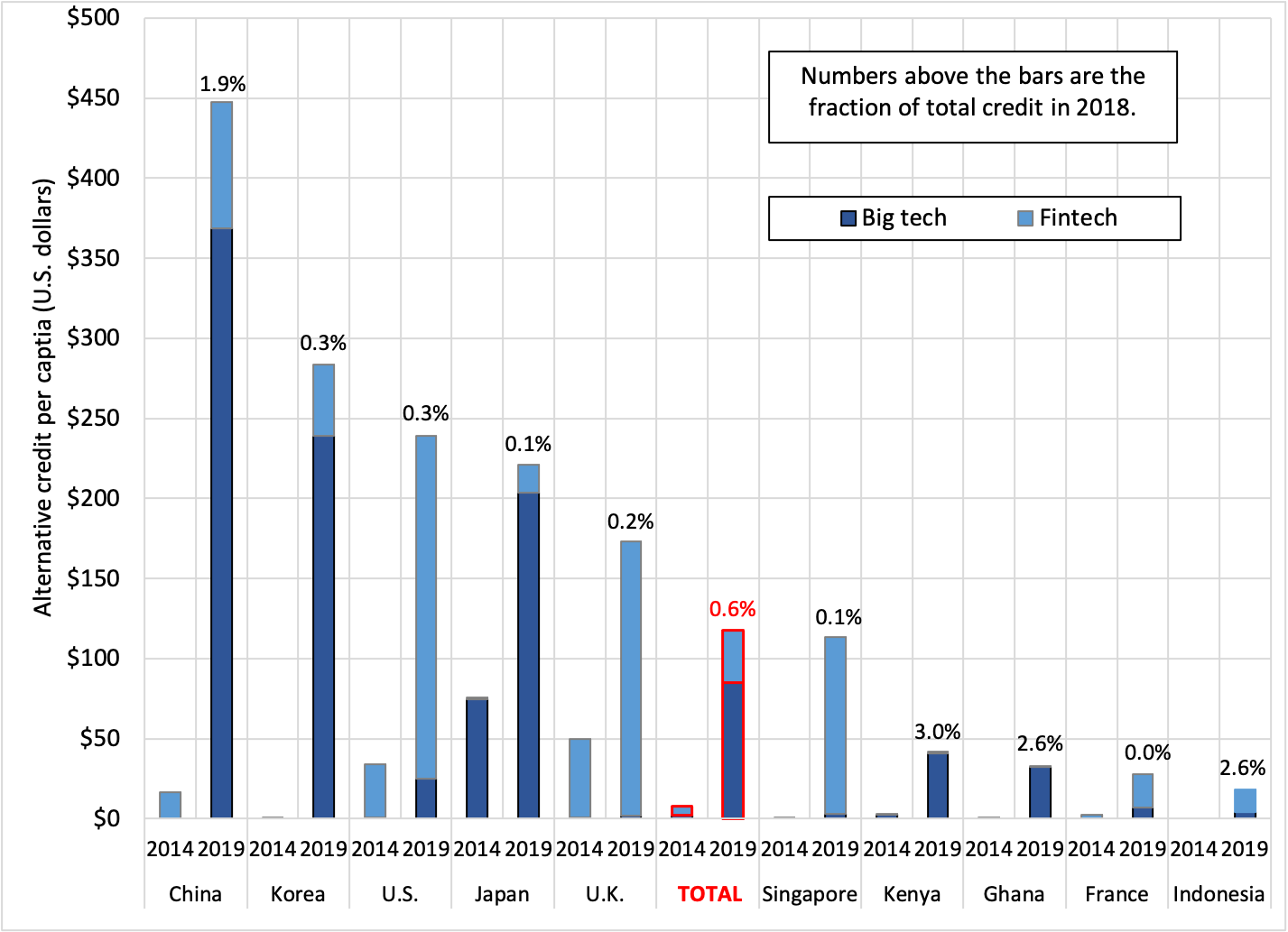

The following chart shows the evolution of per capita credit from tech firms for the top ten countries in the Cornelli et al. dataset. Ranked by their 2019 level, the bars show the portions due to big tech (dark blue) and fintech (light blue) separately. The numbers above the bars are the fractions of total credit accounted for by these alternative sources in 2018 (the latest available).

Big tech and fintech credit, per capita in U.S. dollars, various years

Source: BIS.

We draw three conclusions from this chart. First, tech credit supply has grown enormously over the past five years. For the entire BIS sample (labelled “TOTAL” in the chart), per capita credit from these sources jumped from $8 in 2014 to $118 in 2019. The aggregate is currently around $800 billion, or 0.6% of total credit. Second, the bulk of the growth—as well as the bulk of the credit—is now coming from big tech. This is most evident from the shares of big tech credit in China, Korea, and Japan. (As we suggest in earlier posts—most recently, here—peer-to-peer fintech lending seems destined to remain small.) Third, tech-supplied credit is now an important and rapidly growing source of finance in China, Kenya, Ghana, and Indonesia where it accounts for a notable fraction of all credit outstanding—between 1.9% and 3.0%.

As a result of the work of Professor Yiping Huang, Director of the Institute of Digital Finance at Peking University, and his collaborators at the BIS and IMF, we have a good sense of what is happening with big tech in China. In two papers (here and here) they examine a massive dataset from MYbank, an online lender associated with Alibaba that offers credit to very small firms, including many that lack access to traditional credit. From January 2017 to April 2019, MYbank made 7 million loans to 2 million borrowers. These loans were small—the median size was RMB 6,900 ($975)—and relatively short-term, with maturity from one month to one year. In the conventional sense, they are unsecured. Over the same 28-month period, other lenders provided these same firms 400,000 unsecured loans with a median size of RMB 60,000 ($8,500), and 95,000 secured loans with a median size of RMB 300,000 ($42,500). The total volume of lending is currently around $540bn, split roughly evenly between the MYbank online loans, secured bank loans, and unsecured bank loans.

Professor Huang and his colleagues draw two important conclusions from their study of the MYbank data, one about cyclical sensitivity and the other about access. On the first, it appears that the supply of unsecured big tech lending is less sensitive than other lending to either local business conditions or house prices. In part, that is because bank lenders react to changes in the value of physical collateral, while big tech lenders react to variation in a firm’s revenue flow. Gambacorta et al. go on to suggest that by substituting data for collateral, big tech lending is less sensitive to asset price fluctuations. As a result, a large shift to big tech lending could weaken the transmission of financial sector shocks and monetary policy actions to the real economy.

Turning to access, as we suggest above, conventional banks shy away from small firm lending because the cost of screening and monitoring is too high. Big tech firms solve this problem by using the information generated through their platforms to improve credit evaluation of the small firms. After developing reliable algorithms, they make millions of small loans rapidly and at very low marginal cost.

How does this work? Recall that big tech firms provide payments services. This means that they observe their clients’ revenue flows in real time and can see quickly when the financial condition of a firm in their network changes. Furthermore, the big tech firm can enforce repayment of a loan at low cost by siphoning off a portion of the client’s revenues during the payments process. The bigger the big tech platform, the more effective the screening, monitoring and enforcement.

As an example, most of our readers are probably regular customers of Amazon. Much of what is on the Amazon website is in fact marketed by others. These Marketplace merchants sell their products on the platform, with customers paying Amazon, which then passes on the revenue (less a fee). Now, Marketplace businesses can borrow through Amazon. The loans range from $1000 to $750,000, with terms of up to 12 months, and rates that seem to vary from 6% to 20%. (Reports are that at the end of 2019, there were just under $1 billion in loans outstanding.) And, if you take a closer look at the terms, you will see that a borrower agrees to allow Amazon to repay the loan from the firm’s Marketplace revenue (see here). In effect, a merchant borrowing from Amazon agrees to make that loan senior to all other creditors.

Similar arrangements exist elsewhere. For example, Risbash and Schäublin study an Indian payments provider that offers very small loans to merchants in its network. The loans average about $500, carry an interest rate of 2% per month, and are repaid by the lender taking a fraction of the payments going through the network. In this case, a borrower can control the speed of repayment by shifting between use of the electronic system and paper currency.

Before continuing, we note that big tech lending may be succeeding where microfinance has not. Started in the 1970s, the intent of microfinance is to provide small loans directly to very poor entrepreneurs. Yet, the system is very costly: Cull, Demirgüc-Kunt and Morduch estimate the median unit cost in operating expenses at $14 per $100 of loan outstanding. As a result, the smallest loans tend to be made by NGOs that subsidize them, not by commercial banks. And, overall, the total quantity of lending remains relatively small. While there are 140 million borrowers, the total credit is still something like $125 billion (see here)—that’s roughly one-sixth the 2019 level of big tech and fintech lending.

Overall, we can see both positive and negative aspects of the increasing big tech supply of credit. On the positive side, they are increasing access, using data to overcome both adverse selection and moral hazard. Their credit evaluation algorithms do this relatively cheaply and quickly. And, since the borrowers are often captive, the big tech firms can do real-time monitoring of the financial condition of the firms and enforce repayment by making themselves senior to all others.

But what about competition for supplying credit? Big tech firms acquire the data because they are big. MYbank can make millions of loans with low default rates because Alipay has 1.1 billion users (see here). (WeChat Pay is roughly the same size.) As a result, merchants are virtually forced to be on these platforms: getting kicked off could be catastrophic. In the United States, Amazon has more than 100 million subscribers and accounts for over 5% of retail sales (excluding autos and gasoline). That is, as the size of the platforms grows and their number shrinks, big tech firms are likely to gain pricing power (if they don’t already have it) that extends to their financial relationships.

Where is this all going? In our view, China is leading the way for the emerging world. In places where banks are not doing their jobs in allocating credit and not innovating, big tech companies face a huge opportunity. Their informational and network advantages allow them to make vast numbers of loans that boost access, productivity, and growth. Moreover, with low default rates, they can offer cheap credit and remain profitable.

In advanced economies, where banks are producing and using information, as well as integrating new technologies into their businesses, the evolution of financial services providers could be very different. Big tech firms generally are still shying away from obtaining their own banking licenses. Instead, we see them creating partnerships in which banks exploit their expensive compliance systems and knowledge of regulation, while big tech firms provide the data and a flow of customers. Meanwhile, banks are investing in technology to provide additional services, as well as capture and process data. (For more details, see here.)

Which way will this go? Will big tech firms in advanced economies manage to capture an ever-larger share of value-added in finance? Or, will big banks remain dominant? The answer will depend on a whole host of things (see our recent paper), not least of which is the legal framework of data ownership and privacy.

To see why information property rights could play a critical role in the evolution of the financial system, consider the implications of the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Under the GDPR, individuals will own and control their own data, possibly with the aid of a data custodian. This means that a loan applicant can supply a third-party lender with the data from their relationship with a big tech firm. If the banks are then able to provide high-quality, low-cost service, they will retain their customers, limiting the incursion of the big tech firms into finance. If not, just look to China for the answer.

We do not know how this will play out. What we can say is that it will likely to happen in the next few years. Fasten your seat belt and enjoy the ride.

We thank our friends Leonardo Gambacorta and Yiping Huang for their insights into tech lending.