From Inflation Targeting to Employment Targeting?

“With inflation having exceeded 2 percent for some time, the Committee expects it will be appropriate to maintain this [0 to ¼ percent federal funds rate] target range until labor market conditions have reached levels consistent with the Committee’s assessments of maximum employment.”

FOMC Post-meeting Statement, December 15, 2021.

Last year, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) modified its monetary policy framework to focus on average inflation targeting. They stated that “appropriate monetary policy will likely aim to achieve inflation moderately above 2% for some time” after “periods when inflation has been running persistently below 2%.” At the same time, the Committee scaled back efforts to preempt inflation, introducing an asymmetric “shortfall” strategy which responds to employment only when it falls below its estimated maximum. FOMC participants view these strategic changes as means to secure their legally mandated dual objectives of price stability and maximum employment (see our earlier posts here and here).

Prior to this week’s FOMC meeting, the Committee’s forward guidance explicitly balanced these two goals. For example, the FOMC’s November 3 statement reads (in part):

“The Committee decided to keep the target range for the federal funds rate at 0 to ¼ percent and expects it will be appropriate to maintain this target range until labor market conditions have reached levels consistent with the Committee’s assessments of maximum employment and inflation has risen to 2 percent and is on track to moderately exceed 2 percent for some time.”

However, in what we view as a remarkable shift, changes in the December 15 statement are difficult to square with any type of inflation targeting strategy. Over the six weeks between the last two FOMC meetings, measures of headline and trend inflation rose farther above the long-run target of 2 percent than at any time in nearly 40 years (see our earlier post). As Chairman Powell noted, this was not the inflation at which the Committee’s strategy aims (page 15 of the December 15 press conference transcript). Yet, the Committee’s new forward guidance—highlighted in the opening quote—removes any mention of price stability as a condition for keeping policy rates near zero. Instead, it focuses exclusively on reaching maximum employment.

In this post, we provide two reasons why such an unbalanced approach is concerning. First, a monetary policy strategy that ranks maximum employment well above price stability is unlikely to secure price stability over the long run. More specifically, when inflation rises far above target and is likely to remain above target for an extended period—as FOMC participants themselves project—the failure to make its decline an explicit condition for setting policy rates risks severely diminishing public confidence in the price stability goal. Second, FOMC participants’ projections for 2022-24 are a combination of strong economic growth, further labor market tightening and a policy rate well below long-run norms. This mix seems inconsistent with the large decline in trend inflation that participants anticipate. While policymakers certainly can and do revise their projections, persistent underestimates of inflation fuel the perception that price stability is a secondary, rather than equal, goal of policy.

Let’s look at our concerns in more detail, starting with how an effective central bank ranks its policy goals. First, in recent decades, those central banks that successfully kept inflation low and stable generally had one of two types of monetary policy mandates: a hierarchical one in which price stability comes first, or a balanced one that treats price stability and maximum employment equally. The ECB mandate exemplifies the former, while the Fed’s mandate is representative of the latter.

In our view, the success of both the ECB and the Fed in securing price stability has come from their systematic policy responses to inflation deviations from their publicly stated objective of 2 percent. Most important, through its impact on long-term inflation expectations, the clarity of this perceived “reaction function” helps make inflation shocks temporary and provides scope for policymakers to ease financial conditions to counter shortfalls of aggregate demand. More generally, under either mandate, delivering price stability requires that households and businesses expect the central bank to counteract persistently high inflation even if that means temporarily accepting a large decline of employment (as in a recession). If a central bank prioritizes employment over price stability, why should anyone believe that authorities will risk a recession to reduce inflation?

For most of the past 30 years, the FOMC has been willing to accept a heightened risk of recession when that is the policy needed to keep inflation low and stable. Moreover, since 2008, the Fed’s policy framework has provided explicit guidance on how policymakers will treat their employment and inflation objectives when (as in current circumstances) the two are not complementary. In last year’s strategy update, the Committee states that policy will take “into account the employment shortfalls and inflation deviations and the potentially different horizons over which employment and inflation are projected to return to levels consistent with its mandate.” In our view, this “balanced approach” is fully consistent with the dual mandate that gives equal weight to price stability and maximum employment. However, the “balanced approach” appears inconsistent with the FOMC’s new forward guidance that commits it to a near-zero policy rate “until labor market conditions have reached levels consistent with the Committee’s assessments of maximum employment.”

To see why see say this, note the size of the current deviations of employment and inflation from the stated FOMC goals. Starting with employment, the unemployment rate has plummeted by a whopping 1-percentage-point in the past three months and is now only 0.2-percentage points above the median FOMC longer-run estimate of 4%. We expect that a humble policymaker would be skeptical about the ability to measure the long-run normal unemployment rate with such precision, let alone treat the small current gap as a policy-critical one. Could it be that the unemployment rate seriously understates slack in the labor market? If anything, the opposite may be true: indicators such as the quits rate and the ratio of job openings to unemployed are at or near unprecedented levels, while Omicron’s surge casts doubt on hopes for an early rebound of the labor force participation rate to pre-COVID levels.

As for inflation, the trimmed mean CPI—a statistical measure of trend inflation—rose by 4.6% over the past 12 months, its most rapid pace in 30 years and more than double the FOMC’s target. Key, forward-looking price components—notably owner’s equivalent rent—suggest a likely continuation of this elevated trend even as other, more temporary, factors (such as commodity prices) recede.

Against this background, how can the FOMC conclude that current deviations from employment and price stability goals—as well as the likely speed of reducing those deviations—are consistent with the continuation of a near-zero policy rate? If anything, we doubt that current conditions warrant a policy rate significantly below the FOMC’s median projected long-run norm of 2.5%. Implicitly, the FOMC is now placing an unusually low weight on restoring price stability.

Second, we find it difficult to square FOMC participants’ projections for economic growth, the labor market and policy rates with their expectation that inflation will recede sharply in 2022 and decline further in 2023 and 2024. Indeed, in 2022 and 2023, even the highest policy rate projection from an FOMC participant is below the median projection for both inflation and the 2.5% long run policy rate norm. Put differently, throughout the three-year SEP horizon, the FOMC median policy rate projection implies a real interest rate at or below zero, never anticipating the need to slow economic growth from its above-trend pace to reduce inflation. How will this happen? We know of no macroeconomic model that implies falling inflation during an extended period when actual growth exceeds potential and the unemployment rate remains below the long-run norm.

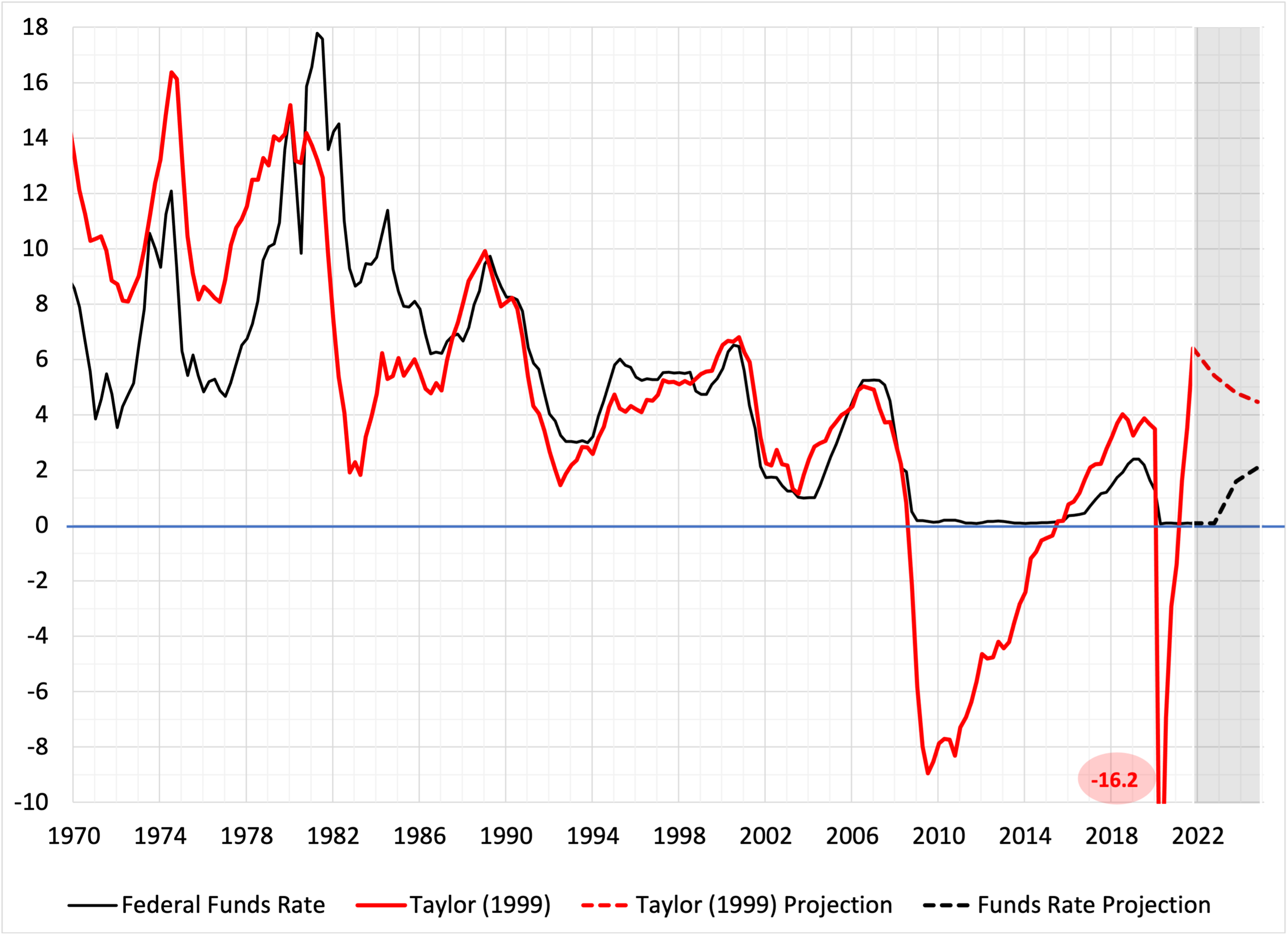

Even if we were to assume that the FOMC inflation projections are correct, a simple Taylor rule—based on the FOMC’s median unemployment and inflation projections—suggests that the FOMC’s projected policy rate (black dotted line in the gray-shaded area) will remain substantially below the projected rule (red dotted line) for several years (see chart). This sizable and persistent policy undershoot of the Taylor Rule would be the first of its kind since the highly inflationary 1970s. (We note that, if inflation fails to decline as quickly or as far as FOMC participants project, then the Taylor Rule gap will be even larger than the one in the chart.)

Federal funds rate vs. Taylor rule, 1970-2024

Notes: Estimates are based on the 1999 version of the Taylor rule that places twice the weight on resource utilization deviations compared to the original Taylor 1993 rule (see, for example, Yellen.) Dashed lines use FOMC median projections for unemployment, inflation and the federal funds rate. They also assume an equilibrium real interest rate (r*) of 0.5%, consistent with the FOMC median longer-run policy rate projection of 2.5%. Shading indicates the projection period.

FOMC participants appear at least partly cognizant of the potential inconsistencies in their inflation projection. According to the latest Summary of Economic Projections (SEP, Figure 4.C), 15 out of 18 participants believe that risks are skewed toward higher inflation than they project, while 0 participants see downside risk relative to their projections. Importantly, this gap between upside and downside risk projections exceeds the gaps in all SEPs since the FOMC began its projections in 2007 (see Figure 4.E). At the same time, FOMC participants unanimously believe that the uncertainty associated with their inflation projections is higher than the norm for uncertainty over the past 20 years (see Figure 4.D).

To be sure, we are currently experiencing unprecedented supply dislocations and demand shocks. This is surely creating heightened near- and medium-term uncertainty. So, what we find most astonishing is that this very high degree of macroeconomic uncertainty is not translating into a widening of the distribution of inflation projections among FOMC members. Consider, for example, the following histogram of 2022 projections for inflation as measured by the personal consumption expenditures price index. Reflecting the recent news, FOMC participants raised their 2021 projections in the December SEP, boosting the median to 5.3% from September’s 4.2%—a whopping 1.1 percentage-point revision in less than two months. But, for 2022, FOMC participants shifted their projections far more moderately, raising the median projection by 0.4 percentage points, from 2.2% to 2.6%. Perhaps more important, the dispersion of projections appears largely unchanged. This lack of dispersion may help explain the remarkable lack of FOMC policy dissents despite the policy imbalance previously highlighted.

Distribution of FOMC participants’ projections for PCE inflation, September vs. December 2021

Source: FOMC Summary of Economic Projections Figure 3.C (September 2021 and December 2021). Note: Numbers above the bars reflect the number of FOMC participants in each projection range.

Conclusion. To preserve its three-decade track record for delivering price stability, the FOMC will soon have to restore the balance between its mandated goals. Perhaps, as the FOMC projections imply, inflation will recede on its own despite continued policy accommodation. More likely, in our view, lingering high inflation will soon test the FOMC’s resolve, prompting further upward revisions of inflation and policy rate projections for 2022 and beyond. Perhaps we also will see a wider dispersion of projections that foreshadows more aggressive policies.

Ultimately, we hope that the FOMC will raise its policy rate soon enough—and boost its projected rates far enough—to restore price stability without serious economic and financial disruptions. The more they hesitate, the more abrupt and disruptive the eventual change in policy likely will be, and the greater the threat to the expansion.