Stopping central banks from being prisoners of financial markets

"I used to think that if there was reincarnation, I wanted to come back as the president or the pope or as a .400 baseball hitter. But now I would like to come back as the bond market. You can intimidate everybody." James Carville, President Bill Clinton’s political adviser, Wall Street Journal, February 25, 1993.

Central banks are on the front lines in the fight to limit the impact of the pandemic. They are supporting virtually every aspect of the economy and the financial system. Going well beyond traditional policies aimed at stimulating aggregate activity, central banks have lent to banks and nonbanks to reduce the likelihood of runs and panics, provided liquidity to ensure financial markets continue to function, and offered credit directly to nonfinancial borrowers as a substitute for private intermediation. Since March 2020, the Fed’s securities holdings nearly doubled and now stand at $7 trillion.

Combined with the massive fiscal support, these policies restored market stability, safeguarded financial institutions, and reduced suffering. Count us among those who firmly believe that everyone would be in worse shape had central banks and fiscal authorities not coordinated this aid as they did.

But, by providing such a broad backstop, the reliance of financial markets on that support can itself become a source of instability. This raises a set of very important and pressing questions: Have central banks’ actions over the past year made financial markets their masters? Can policymakers now be counted on to suppress financial volatility wherever it arises?

We surely hope not, but we see this as a legitimate concern. Fortunately, we also see a solution. Central bankers should strive to duplicate the success of their framework for interest rate policy. That is, they should be clear and transparent about their reaction function for all their policy tools. Knowing how policy will react, markets will respond directly to news regarding economic conditions, and less to policymakers’ commentary. Of course, central bankers cannot ignore shocks that threaten economic and price stability. But cushioning the economy against large financial disturbances does not mean minimizing market volatility.

To be clear, there are times when central banks intentionally make themselves the prisoners of markets. But, in these exceptional circumstances, policymakers go in with their eyes open. They know that the policies they adopt sacrifice control of their balance sheet. Two specific cases are an exchange rate system like the one the Swiss National Bank adopted in 2011, and the ongoing yield curve control policy of the Bank of Japan. It is worth taking a moment to describe each of these, if for no other reason to emphasize that the Fed is not in a comparable position.

Starting with the Swiss, as the euro area crisis intensified in 2011, a large flight to safety drove the value of the Swiss Franc up from CHF 1.30 per euro in April to about CHF 1.03 per euro in August. Concerned that this was harming Swiss producers, on September 6, the Swiss National Bank (SNB) announced that they would “no longer tolerate a EUR/CHF exchange rate below the minimum rate of CHF 1.20.” The official press release went on to say that “[t]he SNB will enforce this minimum rate with the utmost determination and is prepared to buy foreign currency in unlimited quantities.”

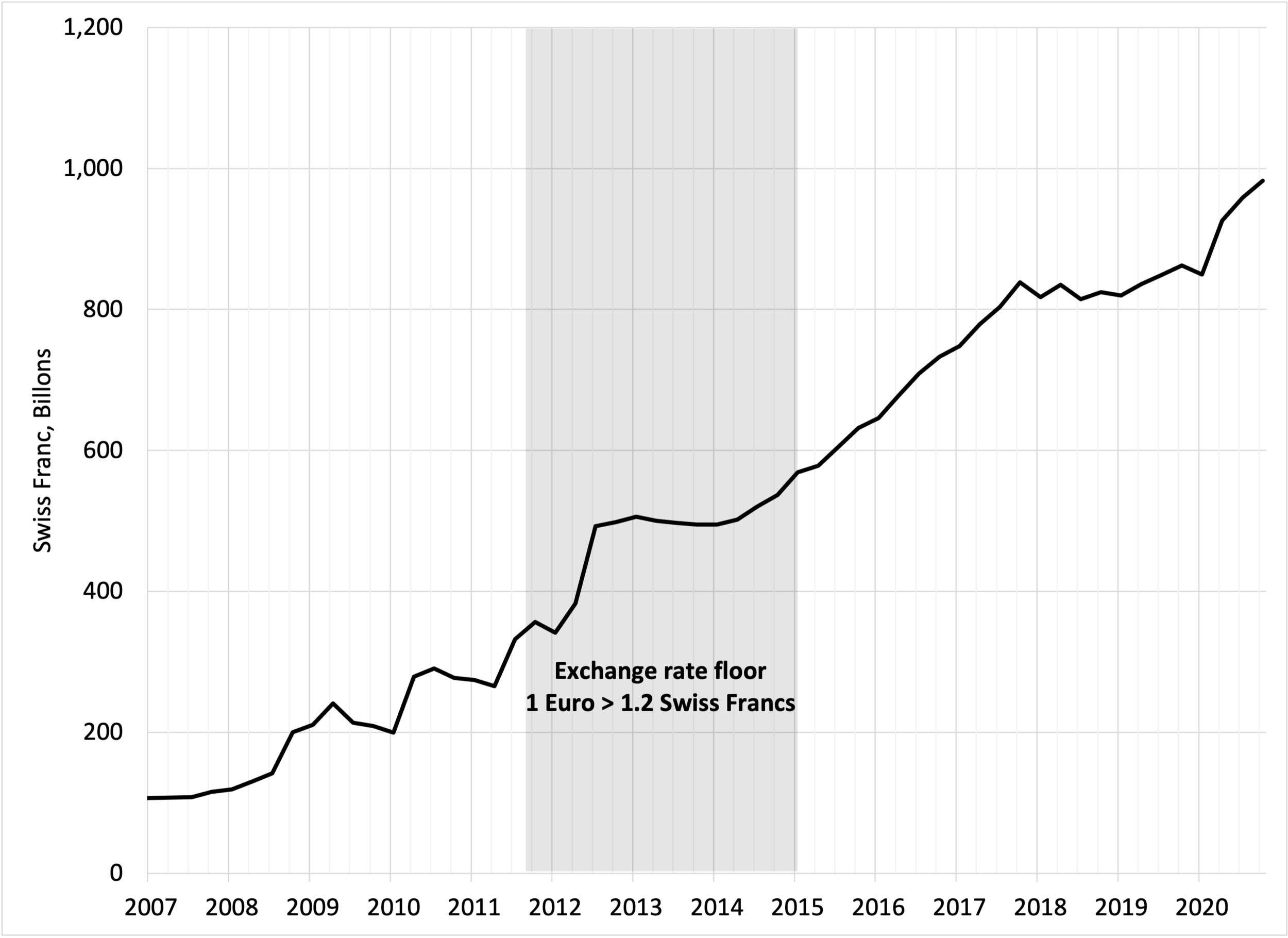

Clearly, the SNB’s governing board knew that the size of their balance sheet would be determined by private demand for Swiss francs. The following chart shows the SNB’s assets relative to GDP since 2007. The shaded gray area from September 2011 to January 2015 denotes the period when the exchange rate commitment was explicitly in effect. Note first that even prior to the implementation of this new policy, the balance sheet is expanding. Then, during the first year of the commitment, the balance sheet grew by nearly 40%. After stabilizing, it started to expand again in late 2014. As their balance sheet approached CHF 600 billion (over 80% of Swiss GDP), policymakers abandoned their 2011 exchange rate commitment (see our contemporaneous discussion here). Interestingly, this reversal did little to slow the balance sheet expansion: by the time the pandemic hit, the SNB held assets worth more than CHF 800 billion, nearly 120% of GDP. Even without an explicit commitment, Swiss central bankers appear to be prisoners of the currency market.

Swiss National Bank Total Assets (Billions of Swiss Francs), Jan 2007-Feb 2021

Source: Swiss National Bank.

Our second example is the Bank of Japan’s yield curve control policy. On September 21, 2016, the BoJ Policy Board announced that “[t]he Bank will purchase Japanese government bonds (JGBs) so that 10-year JGB yields will remain more or less at the current level (around zero percent).” That is, in addition to setting the short-term policy rate, they committed to purchase government bonds to maintain a 10-year yield at zero.

The balance sheet consequences have not been all that dramatic (see the chart below). In fact, BoJ assets rose by roughly twice as much from March 2013 to September 2016 as they did from the onset of the yield-curve-control policy until the start of the pandemic. Nevertheless, the commitment means that, if investors rush to sell, the BoJ could end up owning all the 10-year JGBs. In that sense, the central bank remains a prisoner of the bond market. (For a discussion of the pitfalls of this policy see our discussion here.)

Bank of Japan Assets (Trillions of yen), Jan 2007-Feb 2021

Source: Bank of Japan.

Whenever central banks become prisoners of the market, they face a risk of financial instability. The most obvious example is the surge in the value of the Swiss franc when the SNB gave up its commitment at the start of 2015. A milder example is the U.S. experience of the “taper tantrum.” Having begun a third round of large-scale asset purchases In September 2012, the Federal Open Market Committee reaffirmed on May 1, 2013, that they would maintain a purchase pace of $85 billion worth of Treasurys per month, without a clear statement of what would cause this to change.

Then, on May 22, Fed Chairman Bernanke stated in testimony: “If we see continued improvement and we have confidence that that’s going to be sustained then we could in the next few meetings ... take a step down in our pace of purchases.” And, at the press conference following the June 19 FOMC meeting, he said “[T]he Committee currently anticipates that it would be appropriate to moderate the monthly pace of purchases later this year.” The chart below shows the jump in the 10-year Treasury yield of about 60 basis points over that month. Importantly, the Chairman’s comments influenced the bond market.

U.S. Treasury 10-year constant maturity yield, May 1 to June 30, 2013

Source: FRED.

Central bankers are rightly concerned about the sensitivity of financial markets to their public statements regarding the likely future path of policy. These can be an unnecessary and harmful source of financial volatility. Fortunately, when it comes to asset purchases, there is a straightforward way to address this risk. In our view, the best way to avoid another episode like the 2013 taper tantrum is for central banks that do not have outright commitments to fix market prices to communicate clearly how they would react to changing economic conditions, highlighting risk and uncertainty (see our discussion here).

The FOMC provides such state-contingent guidance for their policy rate in the quarterly Summary of Economic Projections (SEP). For example, based on the March 17, 2021 edition, 11 of the 18 FOMC participants believe that economic conditions will not change sufficiently to warrant any interest rate change before at least 2024. Interestingly, we also know that from December to March their perceived balance of risks for inflation shifted markedly higher (see Figure 4.C on page 14). Amid heightened uncertainty, what were downside risks suddenly became upside risks, even though the expected interest rate path was largely unchanged.

It is natural to think that communication about interest rate policy would be complemented by equally informative discussions of the likely path of balance sheet policy. Here, however the details are scarce. Simply repeating the vague December statement, in March the FOMC announced that the central bank “will continue to increase its holdings of Treasury securities by at least $80 billion per month and of agency mortgage-backed securities by at least $40 billion per month until substantial further progress has been made toward the Committee’s maximum employment and price stability goals.” This leaves very wide discretion regarding what will cause purchase plans to change. Surely there are conditions that will to lead an increase or a decrease. We can also envision circumstances when the Fed would decide to start selling securities, actively reducing the size of their holdings. What are they?

We appreciate the difficulty of formulating a simple policy rule (like a Taylor rule) for the size and composition of the central bank’s balance sheet. That said, following a recent suggestion by Bordo, Levin and Levy, policymakers could develop a set of scenarios for the evolution of the economy and give some sense of how they might adjust their balance sheet in each case. The FOMC would then report the results of the exercise in the SEP, expanded to include the scenarios and a summary of the participants’ views of likely balance sheet responses. Such an enhanced SEP would improve our understanding of what will lead asset purchases to accelerate, slow, or even reverse. Financial markets would then react to changes in the economic environment.

Of course, central bankers cannot ignore shocks to financial conditions that influence economic activity. If, out of the blue, the U.S. equity market were to plunge by 20 percent and remain there, FOMC participants probably would lower their projections for inflation and growth, leading them to alter policy. But such economic stabilization does not mean targeting, much less eliminating, the volatility in the market for equities or other risky assets.

The bottom line: If the news is mostly in the data releases, and less in policymakers’ public statements, the risk that central bankers become prisoners of financial markets is likely to be low.