TradFi and DeFI: Same Problems, Different Solutions

“When new technologies enable new activities, products, and services, financial regulations need to adjust. But, that process should be guided by the risks associated with the services provided to households and business, not the underlying technology. Where possible, regulation should be ‘tech neutral’.” Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, Remarks at American University Kogod School of Business, April 7, 2022.

“[S]tablecoins start with a convoluted and inefficient base technology in order to avoid intermediaries, and then add intermediaries (often with apparent conflicts of interest) back in.” Professor Hilary Allen, Financial Times, May 25, 2022.

In our primer on Crypto-assets and Decentralized Finance (DeFi), we explained that, so long as crypto-assets remain confined to their own world, they pose little if any threat to the traditional finance (TradFi) system. Indeed, the fact that the recent plunge in the market capitalization of crypto-assets (from a peak of $2.7 trillion to November to only $1.1 trillion today) had virtually no impact on TradFi suggests that these assets are systemically irrelevant—at least, for now.

Yet, some crypto-assets are being used to facilitate transactions, as collateral for loans, as the denomination for mortgages, as a basis for risk-sharing, and as assets in retirement plans. And, as we write, many financial and nonfinancial businesses are seeking ways to expand the uses of these new instruments. So, it is easy to imagine how the crypto/DeFi world could infect the traditional financial system, diminishing its ability to support real economic activity.

In this post, we highlight how the key problems facing TradFi (ranging from fraud and abuse to runs, panics, and operational failure) also plague the crypto/DeFi world. We also examine the different ways in which TradFi and crypto/DeFi address these common challenges. To summarize our conclusions, while the solutions employed in TradFi are often inadequate and incomplete, features such as counterparty identification and centralized verification make them both more complete and more effective than those currently in place in the world of crypto/DeFi. Ironically, addressing the severe deficiencies in the current crypto/DeFi infrastructure may prove difficult without making highly unpopular changes that make it look more like TradFi—like requiring participants to verify their identity (see, for example, Makarov and Schoar and Crenshaw).

This is the second in our series of posts on crypto-assets and DeFi. In the next one, we will examine regulatory approaches to limit the risks posed by crypto/DeFi while supporting the benefits of financial innovation. The overarching regulatory principle, restated in the latest G7 communiqué, is simple: “same activity, same risk, same regulation.” Or, as Secretary Yellen puts it in the opening citation: the goal is “tech neutral” regulation. Nevertheless, achieving that goal seems far from simple.

TradFi and DeFi: The Challenges

Advocates of crypto-assets and DeFi aspire to create a system that efficiently satisfies the full range of financial needs without reliance on traditional (centralized) intermediaries. To do this, they create systems in which computer code can execute and verify the legitimacy of financial transactions without the need either for trust in counterparties or for financial institutions as we know them. If successful, crypto-assets and DeFi would substitute for TradFi across all financial activities—ranging from saving, advising, and safekeeping to lending, underwriting, asset management, and risk transfer.

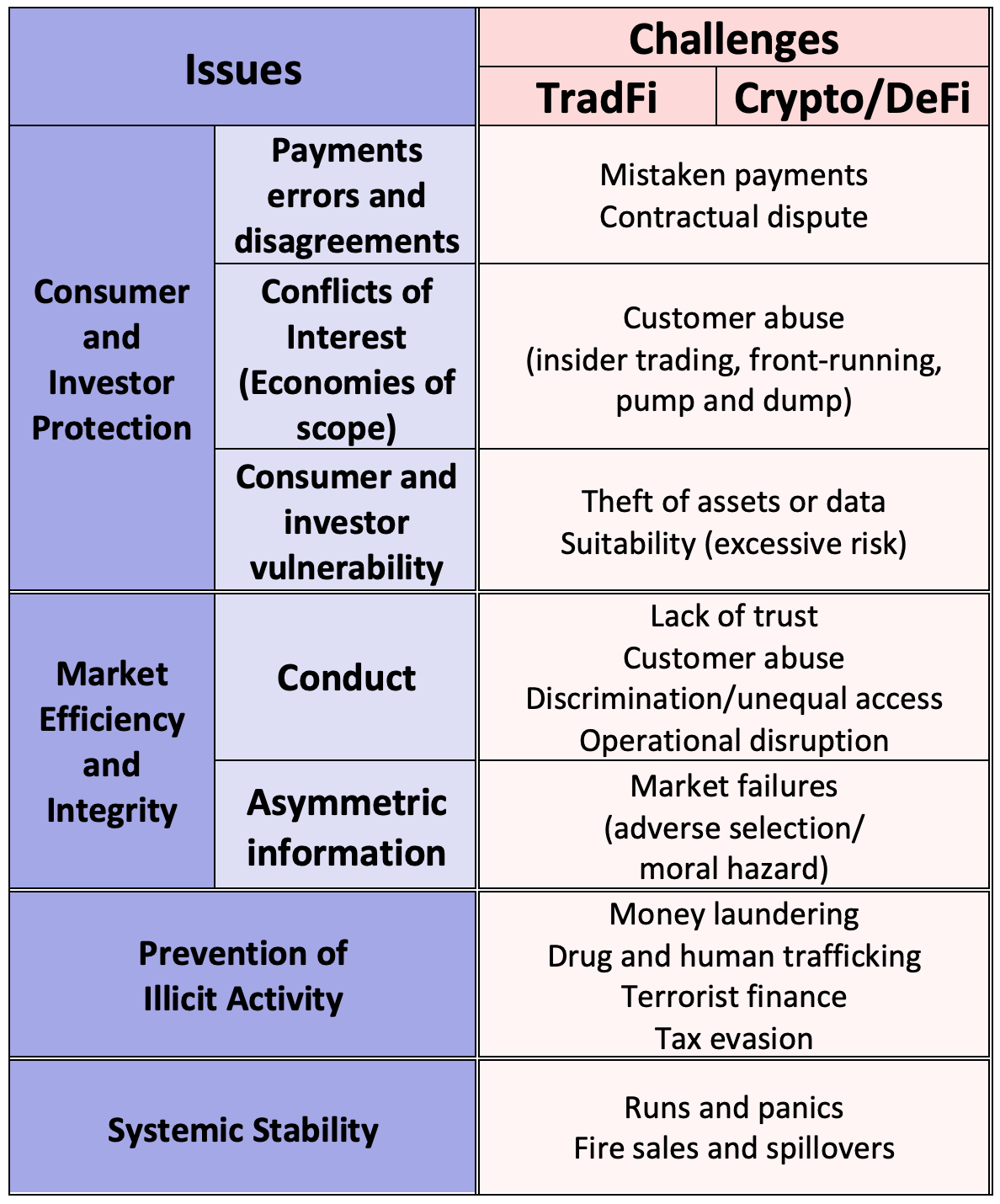

If crypto/DeFi engages in the same activities as TradFi, then it is easy to see why the challenges facing the two systems will be similar: their problems are mostly linked to the nature and underlying economics of the activities themselves, not to the processes that deliver them. In the following table (blue column), we simplify the basic issues facing any financial system into four (overlapping) categories: consumer and investor protection; market efficiency and integrity; prevention of illicit activity; and systemic stability. While far from comprehensive, each cell in the pink column provides prominent examples of the issues that we highlight.

Consumer and investor protection needs arise for variety of reasons, including contractual disagreements, customer abuse (resulting from conflicts of interest and economies of scope), and the vast differences of sophistication among financial service providers and their customers, among others. Examples of each of these abound, including payments errors (or related “fat-finger” events), front running of investors’ orders, insider trading, and outright theft. Not surprisingly, all of these exist in both worlds. But, comparing the two systems, the combination of technological novelty and less government oversight invites those intent on exploitation to take advantage of the opportunities in the crypto/DeFi world. (This is likely one reason that DeFi hacks appear to be rising in frequency and value.)

Market integrity focuses primarily on trust and access. In the TradFi world, integrity depends on the conduct and resilience of institutions. Where activity remains centralized, institutions matter in crypto/DeFi, too. For example, the leading platforms for trading many crypto-assets typically function as centralized intermediaries. And, as the opening quote from Hilary Allen highlights, stablecoin issuers are centralized as well. These arrangements pose risks. In the case of the trading platforms, investors may lack custodial protections if a platform on which they trade should fail; and, absent any legal requirements, reserve-backed stablecoin issuers need not be fully transparent about the assets they hold.

Moreover, the fact that trust and access in crypto/DeFi depend on the “conduct” of algorithms creates a new set of challenges. For example, actions undermining trust—such as simply taking some else’s assets—may not even be a crime, fueling uncertainty about property rights (see, for example, here and here). Under the crypto/DeFi view that “code is law,” a hacker outwitting a smart contract’s protocol is not acting illegally (for the limits of crypto/DeFi efforts to enforce such “code deference,” see Hinkes). Indeed, in the DeFi world, it is not clear who could be held responsible if a smart contract—which is merely a computer protocol—fails to perform as its coders or users anticipate.

Market efficiency focuses on transaction costs and market function. New technology that broadens access, increases choice, and reduces transaction costs has been a key driver of change in TradFi for centuries. In that sense, the innovation in crypto/DeFi is not new. Similarly, with regard to market function, asymmetric information problems that give rise to adverse selection and moral hazard are endemic to all financial relationships and have long undermined the capacity of financial markets to support real activity. In theory, by lowering information costs, new technology could help make markets more efficient (consider the successes of WePay and Alipay in China).

However, there is little evidence so far that this is how crypto/DeFi is functioning. If anything, DeFi creates new information asymmetries—such as the potentially gaping differences of understanding between protocol developers and users—that allow for exploitation. Ironically, even though all the code underlying the crypto/DeFi system is open source and publicly available for everyone to see, it seems unlikely that anyone knows how these complex conditional financial protocols—built up from a set of smart contracts—will function in most (let alone all) states of the world.

Prevention of illicit activity is the challenge that has received the greatest attention. The concern is that criminals will exploit the new system to support drug and human trafficking, terrorism, sanctions violations, and the like. Naturally, these problems have long existed in the TradFi world, facilitated by the willingness of leading jurisdictions to supply anonymous, large-denomination notes that are used to launder money (see, for example, Rogoff).

Ironically, however, the very efficiency of digital transactions—as opposed to physical cash—suggests that the potential for illicit activity in crypto/Defi exceeds that in TradFi. As many observes emphasize, while the crypto/DeFi world prides itself on its open-source code and open access to the blockchain, it remains costly to link blockchain addresses to the beneficial owner of the assets they record. (Firms like Chainanalysis provide forensic tools to analyze suspicious activity.) So, while crypto pseudonymity (the use of an alias) is not as extreme as cash anonymity, it encourages some to try to conceal illicit transactions.

So far, however, the scale of crypto crime appears to be relatively small. For example, according to Chainanalysis, $14 billion worth of crypto transactions went to illicit addresses in 2021. By contrast, the UN Office of Drugs and Crime estimates that money laundering transactions range between $800 billion and $2 trillion annually.

Systemic stability is the ultimate challenge for both the TradFi and the crypto/DeFi worlds. Here, we see close analogies between the likely sources of instability. Consider, for example, the nearly exact correspondence between money market funds and stablecoins. Both aim to maintain fixed value relative to a fiat currency. Both structures create “first-mover advantage”: when concerns about the liquidity of their backing arise, so investors who exit early are more likely to receive full value.

This inherent vulnerability has led both to experience runs. Restoring stability following runs on money market funds required emergency U.S. central bank action in both 2008 and 2020. Despite the brief history of stablecoins, we already have the Iron-Titan episode in June 2021 and the collapse of Terra and Luna in May 2022. As with money market fund crises, crypto/DeFi disruptions have potential systemic implications, as they can trigger fire sales of the assets used as collateral to sustain stablecoin pegs.

TradFi and DeFi: The Solutions

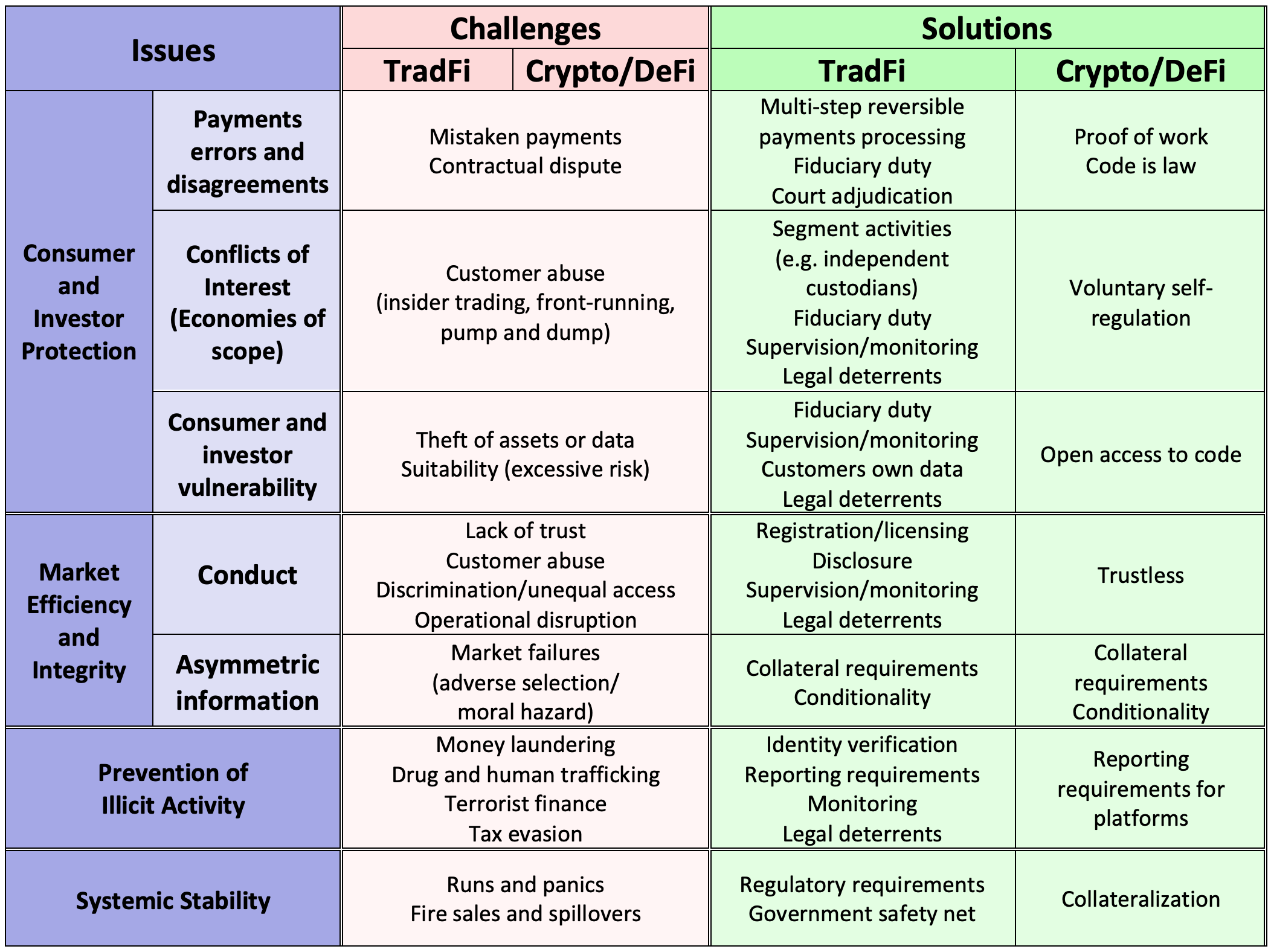

While they remain far from perfect, the solutions to the problems in the TradFi system have evolved over centuries. By contrast, there has been very little time for crypto and DeFi to develop effective remedies. At this stage, the differences in the two sets of remedies reflect both technology and aspirations. For example, the crypto/DeFi world aims for automated, code-based solutions that avoid both the discretion and trust in institutions that characterize TradFi remedies. However, as indicated in our primer, we question whether it is desirable or even possible for any financial system to ever be completely decentralized.

Turning to specifics, the green columns in the following table highlight notable differences in the solutions for each of the four categories of issues that affect both TradFi and crypto/DeFi. Starting at the top, consider the various aspects of consumer and investor protection. When there is a mistaken payment or other type of execution error, TradFi relies on the fiduciary obligations of institutions to protect consumers and investors. The well-established multi-step TradFi payments process allows for some reversibility to correct such errors, while courts can help settle residual disputes. In contrast, in the crypto/DeFi world, verification methods like proof of work (see our primer) ensure that transactions are authentic. However, there is no simple means for reversing errors (like fat-finger events). Moreover, the “code is law” ethic is antithetical to a court’s discretionary adjudication of contractual disputes.

To limit customer exploitation or to manage conflicts of interest that lead to customer abuse, TradFi authorities employ a variety of tools. These include supervision, the imposition of fiduciary duty, the segmentation of selected activities (such as the requirement for independent custodians for investments), rules for data protection, and a range of civil and criminal legal deterrents. In contrast, even where crypto activities are centralized—such as the trading platforms and stablecoin issuers mentioned previously—customers are forced to rely primarily on voluntary self-regulation. Where there is little centralization, open access to the blockchain allows transaction-level monitoring, but there are no rules preventing, say, front-running of customer orders by the “miners” who update the blockchain (see, for example, here).

Turning to market efficiency, the tools for overcoming information asymmetries are remarkably similar. For example, in the case of loans, both collateral and contract conditionality are common means of managing adverse selection and moral hazard. Furthermore, external measures of creditworthiness (such as household or business credit ratings) also can be used to improve the pricing of risk.

In contrast, the TradFi tools for preventing illicit activity are far more extensive than those in the crypto/DeFi world. As we have already seen, despite the transparency of the blockchain, crypto pseudonymity makes it costly to identify beneficial owners. To be sure, when they are located in jurisdictions that comply with global Financial Action Task Force rules, centralized crypto platforms must identify customers and report suspicious transactions (see, for example, here). However, some crypto users strongly object to being identified (see here). And, direct enforcement simply is not feasible in the DeFi world of smart contracts on permissionless blockchains (distributed ledgers) that involve no institutions.

Finally, there is systemic stability. To enhance resilience, regulators and supervisors impose liquidity and capital requirements on TradFi institutions that have access to the government safety net in a crisis. These restrictions are designed to prevent runs and to limit the spillovers and contagion should they occur.

Lacking both the safety net and the accompanying regulatory framework, the key mechanism today for limiting instability in the crypto/DeFi world is the collateralization of liabilities. In this case, it is the extent and quality of the collateral that determines safety. For example, a dollar-linked stablecoin backed 100% by Treasury bills would be very unlikely to face a run. And, even if one should occur, there would be few if any systemic implications since spillovers to the rest of the financial system would be minimal.

TradFi and DeFi: Faults with the Solutions

Current solutions to finance’s common problems are far from perfect. Despite the long experience of TradFi institutions and their regulators, we still frequently observe fraud, theft, customer abuse, discrimination, operational disruptions, market failures, money laundering, and systemic stresses associated with nonbank intermediaries and key markets. As we see in the orange columns of the following table, these shortcomings reflect a wide range of flaws in the solutions: disclosure and monitoring are inadequate, data ownership is unclear, capital and liquidity requirements are insufficient, risk management incentives are poor (not least because of the government safety net itself), and there is overreliance on the discretion of central authorities (including judges and regulators).

Nevertheless, the flaws in current crypto/DeFi solutions (where solutions exist) are even more glaring. There are no mechanisms for reversing mistaken transactions or for requiring institutions to bear the costs of their errors. And, by eschewing court adjudication, the crypto/DeFi world offers no sure and tested path to resolve disputes when, say, a smart contract does not perform as expected.

Similarly, there are no reliable means for limiting the widespread conflicts of interest that fuel customer abuse. Miners can extract value by front-running those who wish their transactions to be recorded in the blockchain. In the absence of independent custodians, crypto platforms that go bankrupt would leave their customers vulnerable to personal loss. And the low cost of introducing new crypto-assets invites insider pump-and-dump schemes that may not even be illegal.

More broadly, in the crypto/DeFi world, vulnerable customers have few protections. As already noted, open access to the code of smart contracts and the blockchain does little to ensure safety. Absent fiduciary obligations and government insurance, crypto platforms are subject to theft and operational failure that can lead to large losses. There are no suitability requirements that would limit crypto/DeFi use to those who understand the complex risks they face. And, even sophisticated investors face potentially unmanageable risks from the lack of court-tested property rights and from the various sources for manipulation (such as opaque trading platforms or the “oracles” that trigger smart contract conditionality).7

Furthermore, it may simply not be possible to limit illicit use of the permissionless blockchains (see our primer) that currently form the backbone of the crypto/DeFi world. As Makarov and Schoar highlight, these structures preserve privacy “by not collecting any personal information about account holders.” In effect, they mimic “an old Swiss model of banking where people could set up anonymous accounts.” Put differently, users can conceal their identities at least until they shift resources to a more centralized (or permissioned) platform with a gatekeeper who (like TradFi intermediaries) collects and verifies the identity of the owner. As we note at the outset, given the sensibilities of many of the participants in this system, fixing these problems is likely to prove exceedingly unpopular.

Finally, there currently are virtually no safeguards for preventing disruptions that can spill over to the TradFi system. Reserve-backed stablecoins are just one prominent example. Pegged to a fiat currency and collateralized by TradFi assets including commercial paper and bank certificates of deposit, they are widely viewed as safe in the crypto/DeFi world (or at least far safer than native coins like Bitcoin and Ether). Yet, like fixed-NAV money market funds, reserve-backed stablecoins are vulnerable to runs that could trigger fire sales of their collateral. Even so, there currently are no rules in place for the reporting or safekeeping of reserves that would make these stablecoins truly safe (and stable).

More broadly, wherever assets in one world fund activities in the other, instability could spill over from crypto/DeFi to TradFi. This means that if crypto-assets are funding traditional financial activity, a sudden change in their value—say, due to a perceived loss of property rights—could expose those engaged in these cross-system asset transformations to a loss of trust and a flight to safety. The more that traditional leveraged intermediaries undertake these transformations, the greater the systemic risk in TradFi.

Ultimately, as Secretary Yellen clearly states, the challenge for regulators is to establish “tech-neutral” rules that preserve stability while fostering healthy and responsible financial innovation. We leave that subject to a future post.

Note: A PDF version of the complete table is available here.

Acknowledgements: Without implicating them, we thank Ethan Cecchetti and Richard Berner for very helpful comments.