Thoughts on the FOMC's Monetary Policy Strategy Review -- Part 2 of 4: Is 2 Percent Still the Solution?

“[C]hanging our inflation goal is just something we’re not thinking about, and it’s something we’re not going to think about… [W]e have a 2 percent inflation goal, and we’ll use our tools to get inflation back to 2 percent.” Federal Reserve Board Chair Jerome Powell, December 14, 2022.

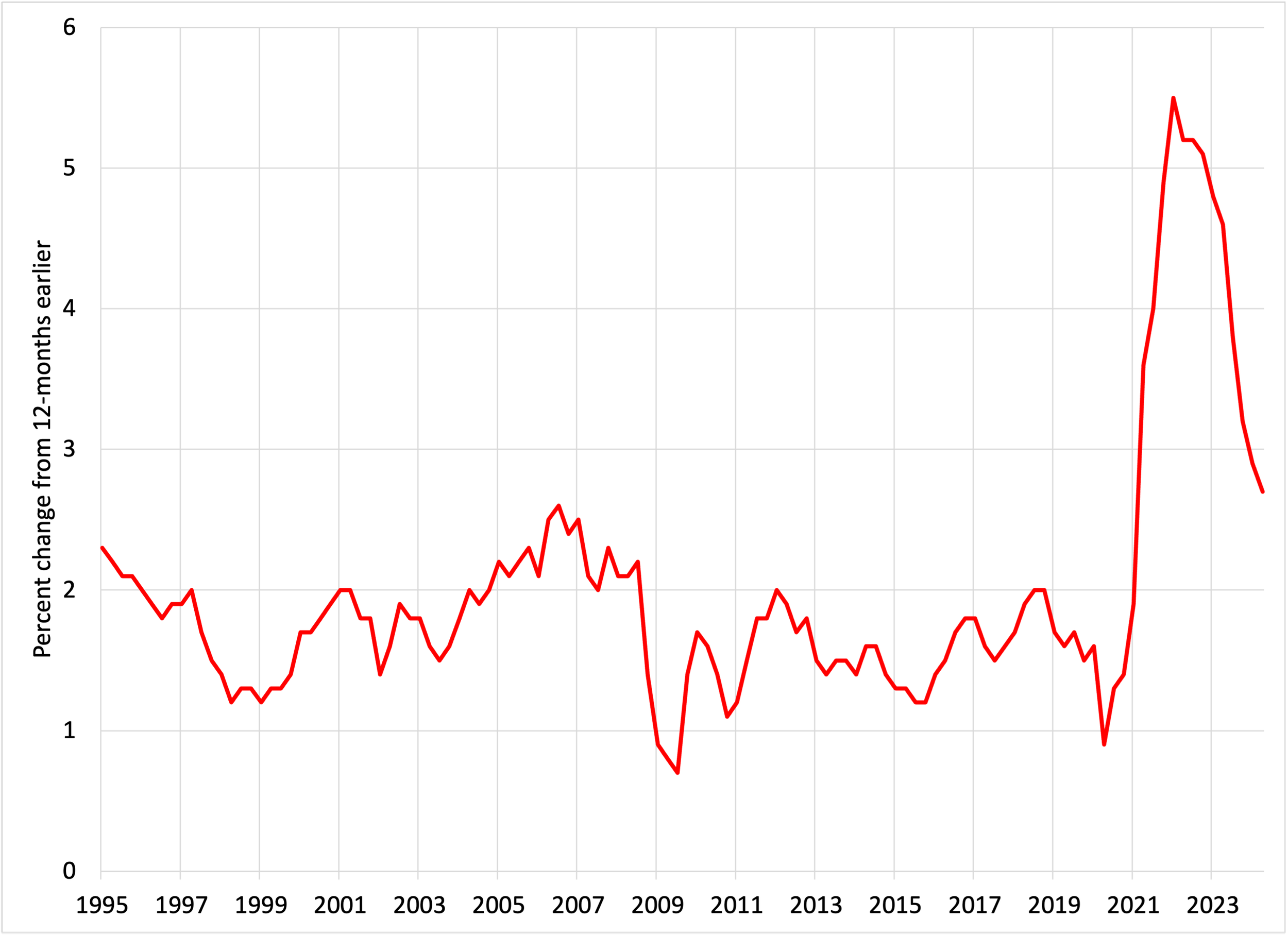

As the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) met in mid-December 2022, inflation using the Fed’s preferred measure (PCE prices excluding food and energy) was running above 5 percent. Under the circumstances, the decision to raise the policy rate from 4¼ to 4½ percent made sense. But as we write, it is more than three years since inflation was at the target (see the chart below). This experience raises the obvious question – and one Chair Powell faced at the press conference in December 2022: Should the FOMC raise its inflation target to 3 percent or 4 percent or even higher? A number of economists – including Laurence Ball, Olivier Blanchard, and Jason Furman – answer yes. In this post, we argue that the Fed should continue to set its inflation target at 2 percent.

Personal consumption expenditures prices excluding food and energy (Percent change from year ago, quarterly), 1995 to 2Q 2024

Source: FRED.

The debate over the appropriate inflation target is as old as the framework itself – now over 30 years. In the end, the choice comes down to a judgement regarding the relative costs and benefits of each option. We discussed these issues in a post from early-December 2022 – shortly before Chair Powell’s comment – and came to the same conclusion that he and his colleagues did. In part, however, our argument rested on the view that raising the inflation target when inflation was still far above the target would undermine the central bank’s credibility. Given the substantial progress in lowering inflation since then, the upcoming strategy review should carefully consider whether 2 percent is still the right long-run target.

In this post, we provide an overview of the arguments for and against raising the target. Our conclusion remains that the Committee should leave things as they are.

When considering the costs and benefits of a particular inflation target, no central bank – even the Federal Reserve – operates in a geographic vacuum. Today, more than a dozen central banks – including the Bank of Canada, the Bank of England, the European Central Bank, the Bank of Japan and the Reserve Bank of Australia – have a 2 percent inflation target. Unless others were to follow, the Fed’s shift away from the current advanced country consensus could have adverse implications for the value of the U.S. dollar, capital flows, and possibly even the stability of strategic alliances.

Leaving aside these important international considerations, in the remainder of this post, we focus on domestic considerations. We first discuss the possible benefits of a higher target, before turning to the costs, which in our view outweigh the benefits.

Benefits of Raising the Inflation Target. We see three benefits of raising the inflation target.

The first, and most compelling, is that it would reduce the asymmetries created by the effective lower bound on interest rates and by policymakers’ aversion to deflation. On the former, in 2017, Kiley and Roberts concluded that with an equilibrium real interest rate (r*) of 1 percent and an inflation target of 2 percent, the policy rate would hit zero roughly 30 percent of the time (see our earlier post). But if we are in a world where r* is 2 percent (or the inflation target is 3 percent), then the frequency of a zero-rate policy in the Kiley and Roberts simulations drops to 20 percent.

The second benefit is closely related to the first: a higher inflation target would allow policymakers to reduce the asymmetry associated with the Fed’s current implementation of flexible average inflation targeting (FAIT). As we highlighted in the first part of this series on policy strategy, under FAIT, the FOMC is making up for undershoots of inflation but not overshoots. As far as we can see, this upward bias arises from the Committee’s understandable unwillingness to let inflation sink close to (let alone below) zero. A higher inflation target would reduce this risk.

Third, a higher inflation target could reduce nominal rigidities, improving the efficiency of prices and wages in allocating resources. Focusing on wages, consistent with employers’ aversion to nominal wage cuts, many people’s wages do not change from year to year. So long as firms resist lowering nominal wages, higher inflation allows real wages to decline as needed to sustain employment when adverse shocks occur.

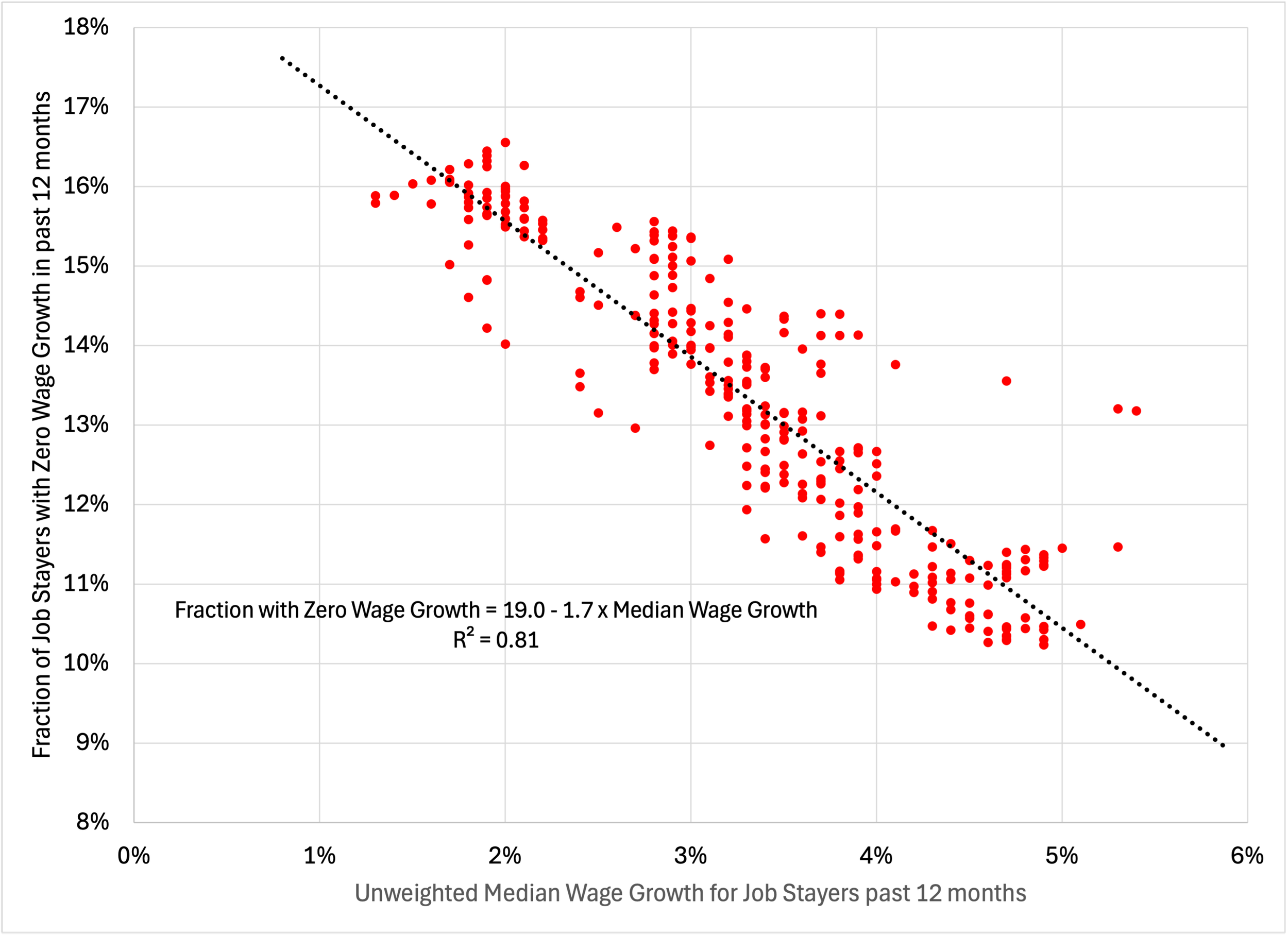

To see the impact on wage-seting that an increase in the inflation target might have, we can look at the following chart, where we plot the relationship between the fraction of job stayers reporting zero wage changes in the prior year (on the vertical axis) against the median wage change on the horizontal axis). As we would expect, with higher wage inflation, fewer workers experience a constant wage.

Fraction of job stayers reporting the same wage as one-year prior vs. the percentage median wage gain from a year ago, 1997-2022

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Nominal Wage Rigidity Data.

Collectively, however, the benefits from raising the inflation target seem limited.

First, continuing with wage rigidity, Grigsby, Hirst and Yildirmaz emphasize the need to look separately at job stayers and job switchers. In their sample from May 2008 to December 2016, over 30 percent of stayers have zero wage change in the prior 12 months (their Figure 2), but only 8 percent of job changers have a zero nominal wage change (their Figure 8). Even in the case of job stayers, the figure above shows that an increase in the inflation target of 1 percentage point (a movement along the horizontal axis) is associated with only a modest decline in the fraction of workers with a zero wage change. In light of the high turnover in the U.S. labor market – nearly 6 million people change jobs every month – it is hard to see how higher inflation would meaningfully improve resource allocation.

Second, our knowledge of r* remains quite imprecise. Using the median forecast, the FOMC’s latest Summary of Economic Projections implies an r* of only 0.75 percent (see their Figure 2). This is close to the current Holston-Laubach-Williams estimate. However, estimates from the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond put the current value at roughly 2½ percent. Moreover, our simple Taylor rule with r*=2 percent (shown in the first post in this series) suggests that it would take an increase of 2 percentage points in target inflation to materially reduce the probability of interest rates hitting zero.

Third, considering events since 2020, we see a continuing heightened likelihood of adverse supply shocks – those that raise inflation while lowering output. Key sources of this risk include fragile supply chains, contagious diseases, geopolitical unrest, commodity shortages, and extreme climate events. Put differently, in the absence of a large fiscal tightening, the prospective mix of demand and supply shocks is less likely than in the decades prior to COVID to threaten deflation and bring the effective lower bound into play.

Costs of raising the inflation target. Balancing these benefits are a set of potentially significant costs. First, a higher inflation target is inconsistent with a credible commitment to long-run price stability. Second, it increases uncertainty, complicating long-term planning that is key for economic efficiency. And, third, it is likely to invite a powerful political backlash, making it difficult to implement, let alone sustain.

In its annual statement on longer-run goals, first published in 2012, the FOMC writes that

“The Committee reaffirms its judgment that inflation at the rate of 2 percent, as measured by the annual change in the price index for personal consumption expenditures, is most consistent over the longer run with the Federal Reserve’s statutory mandate.”

That mandate is to “promote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates." Having argued for a dozen years that, in line with the global consensus, 2 percent is consistent with price stability, can policymakers now raise the target? We doubt that the FOMC could do this without a change in their legislative mandate. If the Committee nevertheless chooses to do so, it would mean reneging on an official 12-year commitment, and on roughly three decades of policy practice. Moreover, after changing the target once, how could officials make a new higher inflation objective credible? Why wouldn’t observers instead expect them to raise the target further whenever it becomes convenient? This seems like a slippery slope to us.

Turning to uncertainty, there is a well-known positive correlation between the level and volatility of inflation. Using a large sample of countries with modest inflation (up to 10 percent annually), we showed in an earlier post that a one-percentage point addition to average inflation is associated with a 0.64-percentage-point rise in the annual standard deviation of inflation. While higher inflation is associated with more frequent price changes, increased volatility reduces the efficiency of everyone’s economic decisions (see here), lowering long-run economic growth.

A higher inflation target also complicates long-term planning for households. With an inflation target of 2 percent, and measurement bias of about 1 percent (see here), “true inflation” probably is about 1 percent per annum. This means that prices – correctly measured – are doubling once every 70 years, only modestly below life expectancy. This pace of increase seems consistent with former-Fed Chair Alan Greenspan’s famous definition of price stability as “the state in which expected changes in the general price level do not effectively alter business or household decisions” (see page 53 here). But, if the target were to rise to 3 percent, again subtracting the measurement bias so that true inflation is 2 percent, prices would double once every 36 years. In that world, inflation becomes more salient, as households would need to consider it when making key long-term decisions such as the scale of savings needed for retirement.

Finally, people strongly dislike inflation, largely because they view it as eroding the purchasing power of their wages (see Stantcheva). That is, people see prices rising more quickly than wages. And, when wages eventually do rise, workers view this as something that they earned, not something that merely compensates them for inflation.

In practice, public dissatisfaction with inflation is now so strong in the United States that it is widely reflected in the views of elected officials. As a result, we doubt that current or future legislators would endorse a higher inflation target. Against this background, raising the inflation target without explicit political support would add substantially to the threats to U.S. monetary policy independence.

To conclude, our view is that increasing the inflation target from 2 percent to 3 percent or higher has costs that significantly outweigh the modest potential benefits. Nevertheless, the upcoming strategy review should carefully consider the possibility of raising the target. Even if, as we expect, policymakers leave the target unchanged, a serious review would highlight the strong evidence for – and reinforce the credibility of – the 2-percent target.