Where Governments Should Spend More

“I think there is a strong case for a substantially more ambitious national infrastructure investment program, perhaps on the order of one percent of GDP each year going forward.”

Harvard Professor Lawrence Summers, January 18, 2017.

As a result of the pandemic, U.S. general government debt (federal, state, and local obligations combined) has surged above 130 percent of GDP, more than double what it was in 2007. And, recent U.S. experience is far from unique. Looking at the G20, average public debt rose from 52% of GDP in 2007 to 74% in 2019 and is projected to reach 91% next year.

Unsurprisingly, as government debt increases, the debate over public spending heats up. Are these high debt ratios sustainable? Should we be cutting spending and raising taxes to reduce what will otherwise be a large financial burden on future generations?

In this post, we emphasize that not all government spending is created equal. Investment in physical infrastructure, as well as in education and health—especially for children—can boost future GDP. Moreover, delaying inevitable outlays can boost long-run costs. As a result, a failure to make productive, self-financing investments due to concerns about the debt would be not only tragic, but counterproductive.

Before getting to the importance of public investment, recall that in order to keep debt from exploding, a government must keep its primary surplus―the excess of government revenues over noninterest spending—equal to or greater than the stock of debt times the difference between the real interest rate on the debt and the rate of growth of real GDP (see here). So long as real interest rates remain extremely low, this debt sustainability condition means that governments can safely support high levels of debt and maintain large deficits (see here).

However, as we note in an earlier post, governments that allow persistent increases in their debt ratio tempt an investor backlash. Should debtholders change their view of the riskiness of sovereign bonds, the risk premium they require would rise. A sudden jump in financing costs could force governments to tighten fiscal policy abruptly. That is, in the same way that investors ran on advanced-economy banks in the Great Financial Crisis of 2007-09, the day could come when they could shun the debt of sovereigns, even that of the United States. But, if sovereign debt is used to finance productive investment that boosts GDP, it is difficult to see why anyone would lose confidence in a government’s willingness or ability to repay.

The bottom line is that there is plenty of room to issue debt so long as the proceeds are used wisely. And it is not hard to find places where there is great need for U.S. public investment.

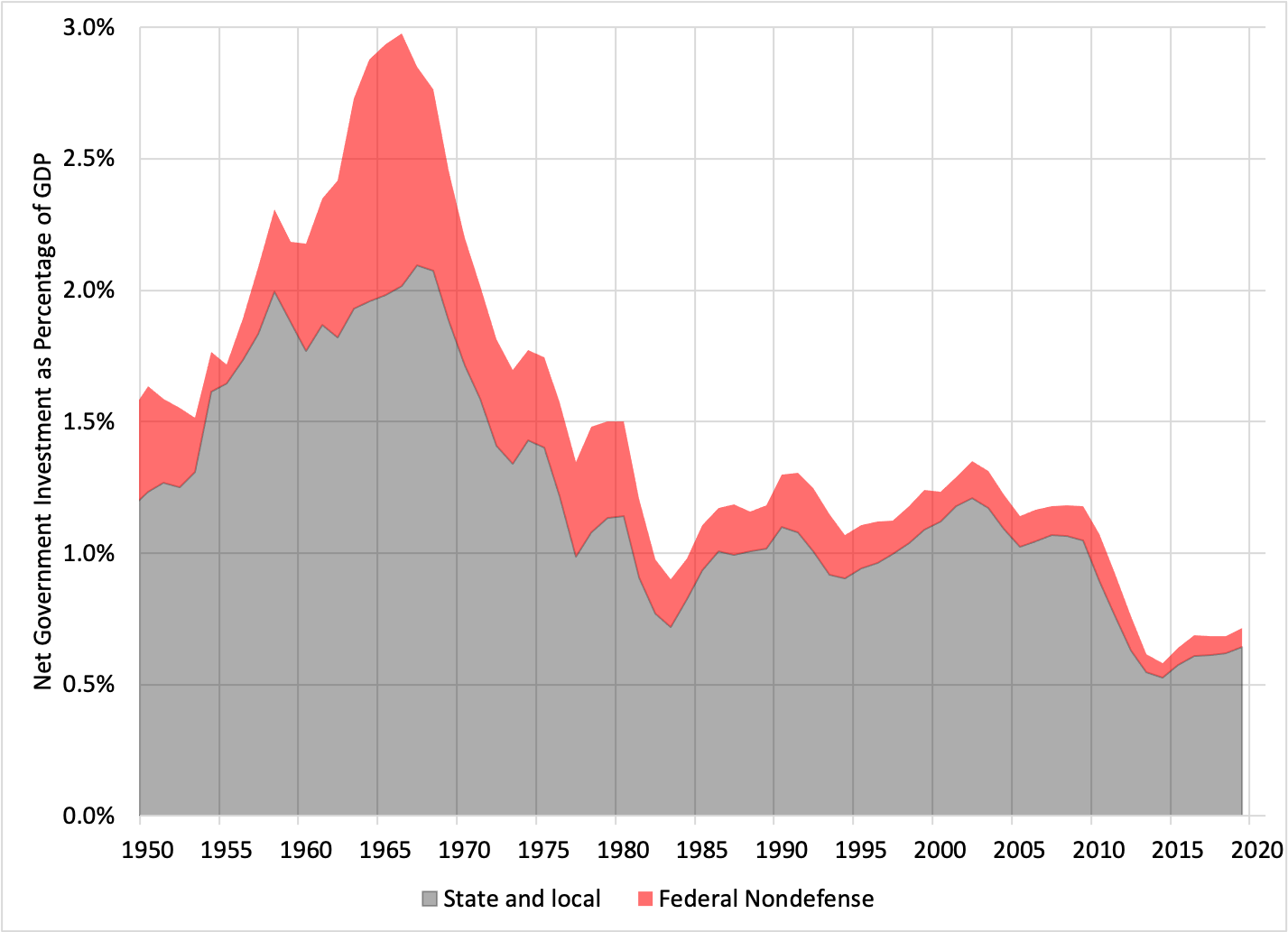

One clear example is the absurd neglect of American infrastructure that is key for economic growth. In the following chart, we plot U.S. government non-defense investment—net of depreciation—as a percentage of GDP. State and local spending appears in gray, while federal outlays are in red. There are two big takeaways. First, state and local governments account for the bulk of net government investment. [The financing is a bit less skewed, with the federal government accounting for something like one-third of the total in recent years (see here).] Second, the level has collapsed. After peaking at nearly 3 percent in the mid-1960s, it fell to just over 1 percent from 1980 to the mid-2000s and is now a paltry 0.7 percent.

U.S. net government non-defense investment (Percent of GDP), 1950-2019

Source: Net government investment, excluding defense, and GDP from Bureau of Economic Analysis, National income and product accounts Table 5.2.5.

Why has state and local investment plunged over the past decade? Since 2007, a combination of slow growth of tax receipts and increases in non-discretionary spending (e.g. interest payments and social insurance contributions) has put these governments under increasing financial pressure. The fiscal squeeze also is evident in employment patterns. From mid-2008 to end-2019, total U.S. employment rose by 10 percent, while state and local employment stagnated.

Looking ahead, medium-term prospects are even worse now than they were a decade ago. State and local governments typically must balance their annual budgets. Absent increased federal support, the COVID crisis will force severe spending cuts. As a consequence of the pandemic, from the end of 2019 through November, state and local employment fell by 1.3 million. Of this, 1 million are in education. Looking ahead, it is difficult to see how these governments will find the means to repair public buildings, roads, bridges, dams, sewage treatment plants, or airports—much less to start anything new—when they are trying to find the resources to pay for their teachers and other key personnel.

Yet, the specter of infrastructure disaster is a serious concern. One quarter of the bridges in the country need repair or replacement. Of the 15,500 dams whose collapse would result in a loss of life, one in seven requires critical repairs. In 2016, the American Society of Civil Engineers estimated that U.S. infrastructure investment need of $2 trillion—10% of GDP. Postponing the repairs likely will make them more complicated and costly.

To understand what we should do, imagine that we are discussing a private business rather than the government. Consider a firm that owns the building where it operates. One day the roof of the building starts to leak. Everyone agrees that that replacement is the right option. But, since carrying out the repair will require borrowing, how should the firm proceed?

The answer is that the owners of the firm should compare the expected future profits (net of the roof-repair loan payments) with the gains from the alternative of selling the business (including the building) and investing the proceeds elsewhere. If the first is larger, they should repair the roof. One of the critical inputs into this calculation is the interest rate on the loan. The lower that interest rate, the more likely that it is worth making the repair. Now, imagine that the interest rate is negative: in that case, either it is worth making the repair, or the business probably should have been shut down already.

This brings us back to government investment. The nominal yield on 10-year U.S. Treasury bonds is currently just below 1%. With the Fed aiming at an average inflation rate of 2%, this means that the federal government’s real cost of borrowing is about -1%. There must be thousands of public projects that meet this extraordinarily low threshold.

Public investment opportunities are of two types: physical infrastructure and human capital formation. On the former, Haughwout suggests configuring federal government infrastructure outlays so that they act as an automatic stabilizer in recessions. Of course, we are not in a typical cyclical downturn—existing home supply has plummeted to new lows, so private construction is booming (see here). But there is surely no shortage of labor in this crisis, so infrastructure investment can still help absorb some of the slack.

With regard to human capital, Hendren and Sprung-Keyser show that numerous government programs more than pay for themselves. That is, their value in higher future wages and lower future government transfers far outstrips their costs. At the top of the Hendren and Sprung-Keyser list are investments in children, especially the health and education of those with low incomes. In other words, cutting programs that help the young and vulnerable is not only mean spirited: it is deeply short sighted.

Putting this together, there is an urgent need for government investment, and this seems like the perfect time to do it. Standard analyses that examine the costs and benefits of debt-financed public infrastructure, health, and education programs frequently conclude that there is a rough balance. A key reason is that these evaluations emphasize the importance of “crowding out”: when the government borrows, interest rates rise, reducing private investment. In the current circumstance, however, with monetary policy intent on keeping nominal interest rates near zero for years, there is little potential for crowding out. That is, the overall social costs of public investment currently look to be far lower than they may have been in the past.

Unfortunately, the nature of the discussion about government debt compounds the challenge we face in ensuring sufficient public investment. The first problem is that governments typically use cash flow accounting for everything. Unlike businesses, they ignore the future returns from an investment, simply treating it as a current expense. In addition, governments fail to account for their contingent liabilities—like the need to make underfunded pension programs whole or to make future—more costly—repairs to failing infrastructure. Together, these practices reinforce the underinvestment in long-lived public capital goods and create a bias away from outright expenditures that boost explicit debt and toward underfunded insurance programs that impose burdens on future generations through implicit debt.

From all this, we draw two conclusions. First, we find Larry Summers’ advocacy for increased public investment compelling (see the opening quote). Government investment is critical to ensuring a well-functioning and vibrant economy. In the United States, it has been too low for too long. The U.S. federal government should borrow to invest, and use its financing capacity aggressively to support the investments of state and local governments. Second, unless we invest wisely, there are limits to the accumulation of government debt. While investors are willing to hold the rapidly increasing supply of U.S. Treasury securities at negative real rates today, one should never count on an uninterrupted continuation of their calm good will.