Fed Monetary Policy in Crisis

“Volcker’s imperfect credibility probably raised the cost of stamping out the 1970s inflation. If the market had more quickly understood Volcker’s persistence as an inflation fighter, the recessions of the early 1980s wouldn’t have been so deep.” Thomas J. Sargent and William L. Silber, The Wall Street Journal, January 11, 2022.

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) is facing a crisis of its own making. The crisis has four elements. Policymakers failed to forecast the rise in inflation. They failed to appreciate how persistent inflation can be. They are failing to articulate a credible low inflation policy. And, so far, there is little sign that monetary policymakers recognize the need to react quickly and decisively. Our fear is that matters have now progressed to the stage where the Fed’s credibility for delivering price stability is at serious risk. And, as experience teaches us, the less credible the central bank, the more painful it is to lower inflation to target (see the citation above from Sargent and Silber and the classic paper by Goodfriend and King).

The first and second failures are now obvious. Inflation is at 40-year highs. Since mid-2021, trend measures, like the median and trimmed mean CPI, reveal prices rising by more than 5½ percent at an annual rate. While studies of inflation during the low-inflation era of the last three decades show little persistence, that statistical pattern is tied to the Fed’s anti-inflation credibility. The recent failures have surely weakened that credibility.

The third failure arises from what now looks to be an ill-timed and incomplete implementation of the FOMC’s new policy strategy in August 2020. The new framework incorporated two key changes: a move to flexible average inflation targeting (FAIT), combined with a shift to a focus on employment “shortfalls,” rather than “deviations” from a sustainable level of employment (see our post at the time.) A key motivation for the new strategy was officials’ doubts regarding their ability to deliver adequate stimulus during periods of near-zero interest rates and very low inflation. As such, the combination of FAIT and labor market patience are designed to have an explicitly inflationary bias.

Yet, even on its own terms, the FAIT framework is incomplete. The point, as we understand it, is that following a period when inflation is below its long-run objective, the short-run inflation target will be above the long-run target to “make up” the shortfall. This temporarily higher target inflation raises short-run inflation expectations and lowers the real interest rate. Even if the nominal policy rate is stuck at zero, the resulting drop in the real interest rate provides stimulus. Yet, the FAIT framework never defined the period over which the inflation averaging is to occur—either looking back or looking forward—making it difficult for anyone to figure out either the size of the shortfall or how quickly the policymakers intend to close the gap (see our earlier post).

More recently, the Fed added to the perceptions of an inflationary bias when Chair Powell suggested that the new strategy is asymmetric. That is, he indicated that the FOMC should aim at inflation above 2% when inflation falls short of the long-run target, but need not aim at inflation below 2% when inflation exceeds it. This asymmetry is inconsistent with securing an average inflation rate of 2% over the long run. (See the exchange between Chair Powell and Michael McKee on pages 22 and 23 of the transcript of the January 26, 2022 press conference.)

Finally, the FOMC’s latest forecasts for inflation and policy rates continue to presume that inflation will largely recede on its own, in contrast with strong and strengthening evidence that the recent rise could very well persist (see the December 2021 Summary of Economic Projections).

In our view, those who now counsel policy patience seriously underestimate both the risks that inflation will remain high and the costs of the Fed losing credibility. It is not sufficient to point to low bond yields as evidence that inflation expectations are under control. As Sargent and Silber argue, the bond market was an unreliable indicator during the Volcker disinflation of the early 1980s and it may be lagging again. The continued mix of expansionary fiscal and monetary policies in 2021 (long after the recovery had gained momentum), combined with the Fed’s remarkably unbalanced approach to its dual objectives, provides strong evidence of a shift in the inflation regime. Moreover, high inflation readings are influencing price- and wage-setting on a scale that we have not witnessed in decades.

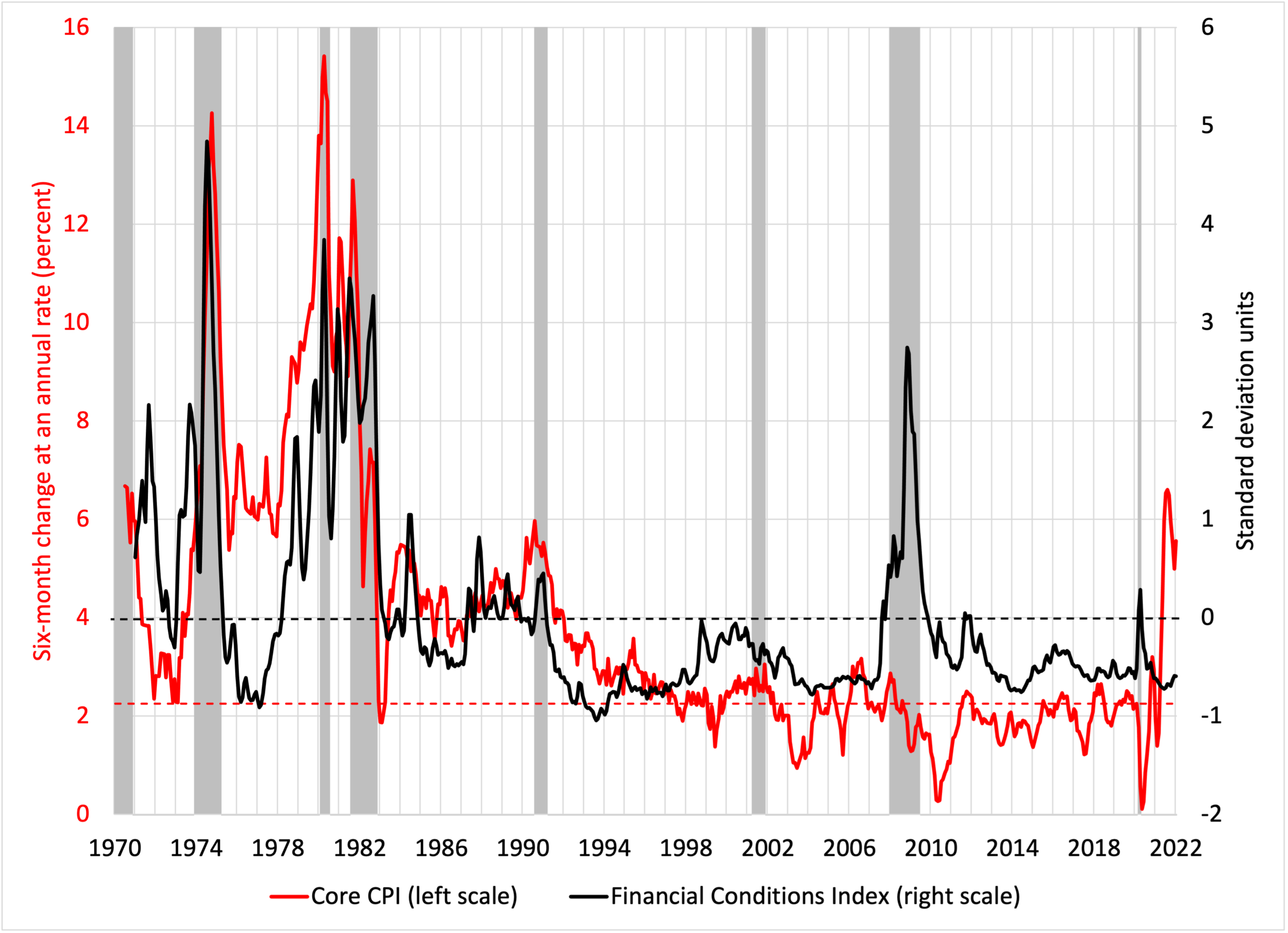

The way to avoid a costly loss of credibility is to act quickly and decisively. Yet, policymakers likely will have a very difficult time catching up. To see why, we can look at some data on inflation and financial conditions. In the following chart we plot the six-month annualized change in the core consumer price index (CPI excluding food and energy) and the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago’s national financial conditions index (FCI). Over the past six months, we can clearly see the outsized pickup of inflation (in red on the left-hand scale). Prices are rising at a rate last seen in the early 1980s during the recession associated with the Volcker Fed’s efforts to bring inflation down from double-digit levels. (Replacing the core CPI with the trimmed mean CPI does not alter this pattern.) Turning to the FCI, the current reading of –0.6 (standard deviation units) implies substantial stimulus. Perhaps most important, the chart shows that, with the exception of the early 1990s, substantial declines in trend inflation came only with sizable tightening of financial conditions and recessions.

Trend Inflation and Financial Conditions, monthly, 1971-2022

Notes: Trend inflation is measured by the six-month annualized change of the consumer price index excluding food and energy (core CPI). Financial conditions are measured by the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago’s national financial conditions index, which has mean zero (dashed black line, right scale)) and standard deviation one over the full sample. NBER recessions are shaded in gray. The dashed red line is at 2¼ percent, which is the level of CPI inflation equivalent to the FOMC’s longer-run inflation goal of 2 percent of the PCE price index. Source: FRED.

Of course, inflation is notoriously difficult to forecast. However, humility about forecast accuracy should encourage greater reliance by policymakers on trend measures of inflation. Put differently, any claim that a positive inflation surprise is transitory embeds the belief that inflation will recede on its own. In recent experience, trend inflation initially rose in April 2021. By June, nearly all measures of core inflation exceeded the Fed’s stated longer-term goal. Combined with the fiscal stimulus and a plummeting unemployment rate, it would have been prudent to begin withdrawing monetary stimulus rather than to rely heavily on inflation-forecasting skills. (As an aside, we note that, starting in March 2021, the Treasury began running down its account at the Fed, increasing reserves in the banking system. This shift would have been a useful opportunity to stop purchasing securities, rather than allowing Treasury’s actions to dictate the aggregate supply of reserves!)

While much of this is water under the bridge, we can learn from past errors. What does experience now imply that policymakers should do? Given the challenge of forecasting inflation, we see three reasons that the FOMC should focus far more attention on incoming data rather than on its projections. First, the prices for some of the most persistent CPI categories are now rising rapidly. These include the cost of shelter (rising by 4.4% at an annual rate) and the price of food away from home (6.4%). From a purely statistical perspective, the upshot is that overall inflation is less likely to recede quickly. Second, as Larry Summers notes, the recent plunge in consumer confidence is likely tied to a rise of inflation expectations that will propel wage demands. Third, given the difficulties that bond investors also face in predicting inflation, policymakers should take less comfort from bond markets about the likely path of inflation.

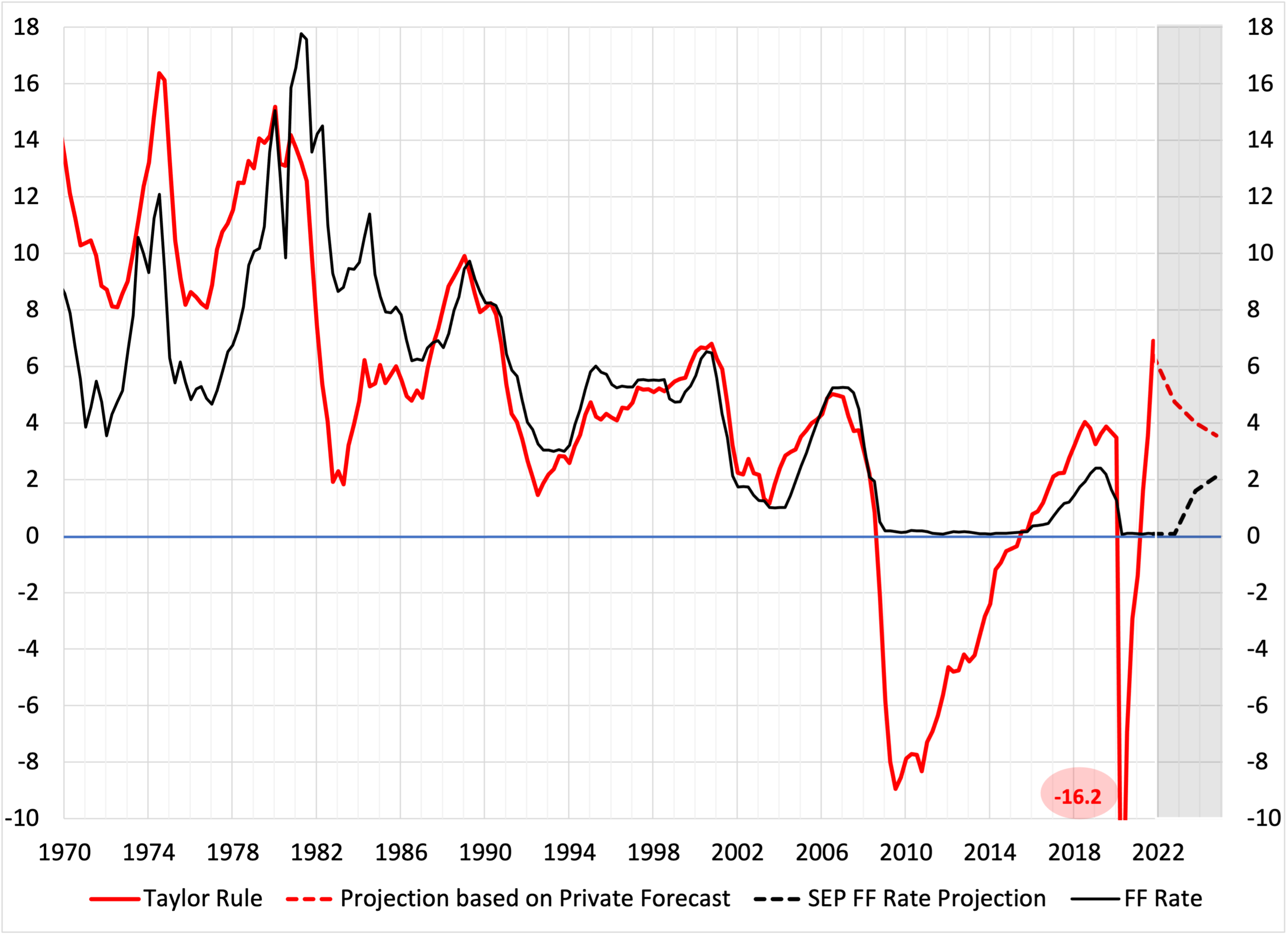

Putting this all together, the FOMC needs a plan to raise rates quickly and substantially. By how much? To get a sense of the magnitudes, we compute a simple Taylor rule and display the results in the next chart. Starting with the history, we show the actual federal funds rate target in black and the Taylor rule rate in solid red. The two follow each other relatively closely from the mid-1980s through 2007. Importantly, however, during periods when the policy rate falls persistently short of the Taylor rule rate, as in the 1970s, inflation tends to rise.

Federal Funds Rate, Taylor Rule rate, and projected rule rates, quarterly, 1970-2024

Notes: The Taylor rule (red) shown is the 1999 version that places twice the weight on resource utilization deviations compared to the original Taylor 1993 rule (see, for example, Yellen). To construct the rule rate, we use the real interest rate from Laubach and Williams, the ex-food and energy PCE price index, a target inflation of 2 percent, and the unemployment rate gap computed using the noncyclical rate of unemployment from the Congressional Budget Office. SEP federal funds rate projections are the median from the FOMC’s December 2021 Summary of Economic Projections. The projection based on private forecasts uses forecasts for the unemployment rate and core PCE inflation kindly provided by Mickey Levy and Mahmoud Abu Ghzalah of Berenberg Capital Markets LLC.

Turning to the more recent period, we see that by the end of 2021, with ex-food and energy PCE inflation running about 4½ percent, the Taylor rule implied a policy rate of nearly 7 percent. Even if core inflation comes down by a percentage point during 2022—that is, by more than the recent trimmed mean PCE inflation rate implies—the projected Taylor rule rate will remain above 5 percent. While it is not obvious from the chart, for the FOMC to ensure inflation returns to its target of 2%, policymakers likely will need to bring the short-term real interest rate into significantly positive territory. Put slightly differently, we suspect that the policy rate needs to rise to at least one percent above expected inflation.

This may seem like a prescription for disaster. Won’t a four-plus percentage-point increase in the policy rate over the course of a year trigger a huge recession? We are drawn to the case of the early 1980s that Sargent and Silber highlight. As they emphasize, credibility is the key to how much pain disinflation will cause. The less credible policymakers are in their commitment to bring inflation down, the worse the recession will be. During the 1970s, the chart above show how reluctant the Fed was to counter the rising inflation trend, until Paul Volcker became Chair in 1979.

Unfortunately, doubts about the Fed’s credibility persisted well into the Volcker era (see Goodfriend and King). Over the course of the 1981-82 recession, as output fell by 2.5% and unemployment rose by 3.6 percentage points, inflation fell nearly 7 percentage points. As severe as the recession was, some observers were surprised by the speed and scale of inflation’s decline. Okun, for example, had previously reported estimates that imply a 10-percentage-point loss in GDP for each 1-percentage-point reduction of inflation.

We consider the outsized scale and pace of disinflation to be Chair Volcker’s enduring legacy. Looking back however, Goodfriend and King argue compellingly that, had everyone believed in Volcker’s resolve from the start, the pain would have been even smaller. They point to the persistent rise of long-term bond yields—while inflation was falling sharply in 1981-82—and to the beliefs of Fed officials (expressed in FOMC transcripts) that people had learned to doubt the Fed’s willingness to stay the course. In their words, “Volcker and other FOMC members viewed the restoration of Fed credibility for low inflation and the associated real cost of a deliberate disinflation in 1981-82 as necessary to prevent future recessions and inflation scares.”

Applying the painful lesson of the 1970s and early 1980s leads us to conclude that the FOMC now needs to show clear resolve. Inflation rose very quickly, so it may still be possible to bring it down sharply without a recession. The more decisively policymakers act, the lower the long-run costs are likely to be. Indeed, we are skeptical of arguments that an aggressive Fed tightening would be particularly damaging over time to those with lower incomes. Rather, the experience of recent decades is that job and wage gains for those with low incomes are most closely associated with long, relatively steady expansions. Failure to restore price stability in a timely way would almost surely render this expansion disturbingly short compared to recent norms.