SEC Money Market Fund Reform Proposals Fall Far Short, Again

“Here we are again. The events of March 2020 suggest that more can be done to improve the resiliency of money market funds […]. This is about systemic risk. Those of us at the SEC have an obligation to the public to once again come back and see if we can shore up this system a bit more.” SEC Chair Gary Gensler Statement on Money Market Reform, December 15, 2021.

We couldn’t agree more. As the principal regulator of U.S. money market mutual funds (MMMFs), the SEC has a duty to end the market distortions and moral hazard that repeated public rescues create. There have been two MMMF bailouts, so far. The first came at the height of the Great Financial Crisis of 2008, while the second followed in the March 2020 COVID crisis. While the Treasury provided guarantees only once, the Federal Reserve offered emergency liquidity assistance both times.

These repeated government interventions encourage MMMF managers to behave in ways that make future liquidity crises more likely. As a result, the authorities are subsidizing liquidity even when there is no direct cost to taxpayers. Moreover, there is no credible way for the Fed to promise not to intervene should a systemic disruption again loom in short-term funding markets. Indeed, Paul Tucker suggests requiring “the issuers of assets treated as safe, regardless of their legal form, to have access to the central bank’s discount window.” The only realistic means to end the subsidies created by the implicit promise of future bailouts is to force MMMFs to be far more resilient than they are today.

Indeed, everyone knows that MMMF regulation needs reform. In December 2020, the President’s Working Group on Financial Markets (PWG) proposed a list of possible MMMF reforms (see our earlier post). The SEC then sought public comments on these proposals. Last June, the Hutchins Center-Chicago Booth Task Force on Financial Stability’s proposed reforms included several aimed at MMMFs (see our earlier post). And, a few months ago, the Financial Stability Board released its own proposals for strengthening the global MMMF industry.

Against this background, the SEC’s December 2021 reform proposals are seriously disappointing. As SEC Chair Gensler suggests, they probably “shore up this system a bit more.” We would go much farther. The proposals are woefully inadequate on several fronts:

Ignoring the functional equivalence between banks and MMMFs, and without providing a quantitative assessment of costs and benefits, the SEC rejects a role for capital requirements.

In calibrating the need for additional MMMF liquidity, the SEC implicitly assumes the continued presence of a Fed liquidity backstop.

The SEC misses the opportunity to compel that MMMF stress tests (which have been required for over a decade) meet fundamental principles of transparency, severity and flexibility.

Even the SEC’s most promising proposal—to require swing pricing for selected MMMFs—is operationally difficult to implement, so (like most useful reforms), it already faces strong resistance from the industry (see, for example, the ICI comment on the PWG proposals, page 5).

In the remainder of this post, we start with basic facts about the scale and mix of MMMFs today. We then describe the SEC’s proposals, before focusing on their key shortcomings. We hope that the public comments that the SEC receives will motivate it, at the very least, to conduct a serious quantitative assessment of introducing capital requirements for the most vulnerable MMMFs, to re-assess the scale of additional liquid assets needed for MMMF resilience in the absence of a Fed backstop, and to propose ways to enhance the effectiveness and utility of MMMF stress tests.

Before proceeding, however, we need to make one thing clear: we do not propose to substitute banks for MMMFs. In our views, MMMFs already function as banks—for the most part, as very safe banks. But if banks are to avoid runs and fire sales, all of them need a mix of risk-adjusted capital and liquidity requirements, along with a lender of last resort (LOLR). The safer the bank, the smaller those capital requirements need to be and the less important the LOLR. But regardless of its structure, regardless of the extent of credit, liquidity and maturity transformation on its balance sheet, every bank needs to issue some capital. To be clear, even a narrow bank that holds only reserve deposits at a central bank requires capital to guard against operational risk. So, the number should never be zero.

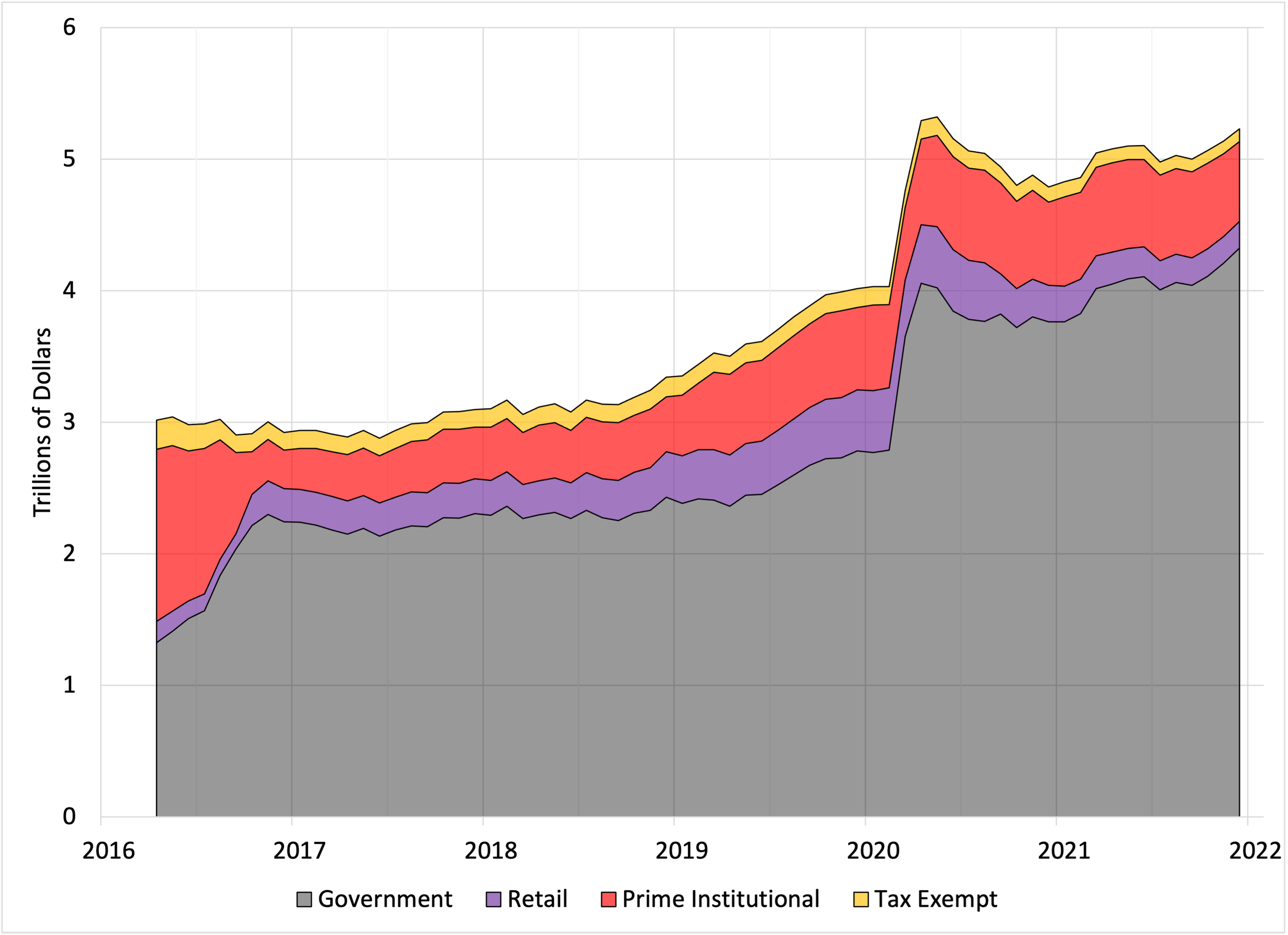

MMMFs by the numbers. Turning to some preliminary facts, there are two types of MMMFs in the United States today: those with a fixed net-asset-value (NAV) and those with a floating NAV. Following the SEC money fund reforms of 2014, government-only and retail funds continue to fix their NAV at $1, but prime institutional and tax-exempt funds must set their NAVs in line with the changing market value of their assets. As we highlight in the following chart, at the end of 2021, government-only (gray) and retail (purple) funds held a combined $4.5 trillion of assets, or nearly 87% of the $5.2 trillion total. Prime institutional (red) and tax-exempt (yellow) funds accounted for the remaining $0.7 trillion.

U.S. MMMF assets by fund category (trillions of dollars), April 2016-December 2021

Source: Office of Financial Research U.S. Money Market Fund Monitor.

The chart highlights two large shifts toward government funds. The first occurred in late 2016, as implementation of the SEC’s 2014 reform requiring prime institutional funds to adopt floating-NAVs loomed. Given the modest sacrifice in return, shareholders revealed their strong preference for the cash-like features of a stable-value (fixed NAV) fund. The second shift came in March 2020 when the COVID crisis prompted a run out of riskier assets into cash equivalents.

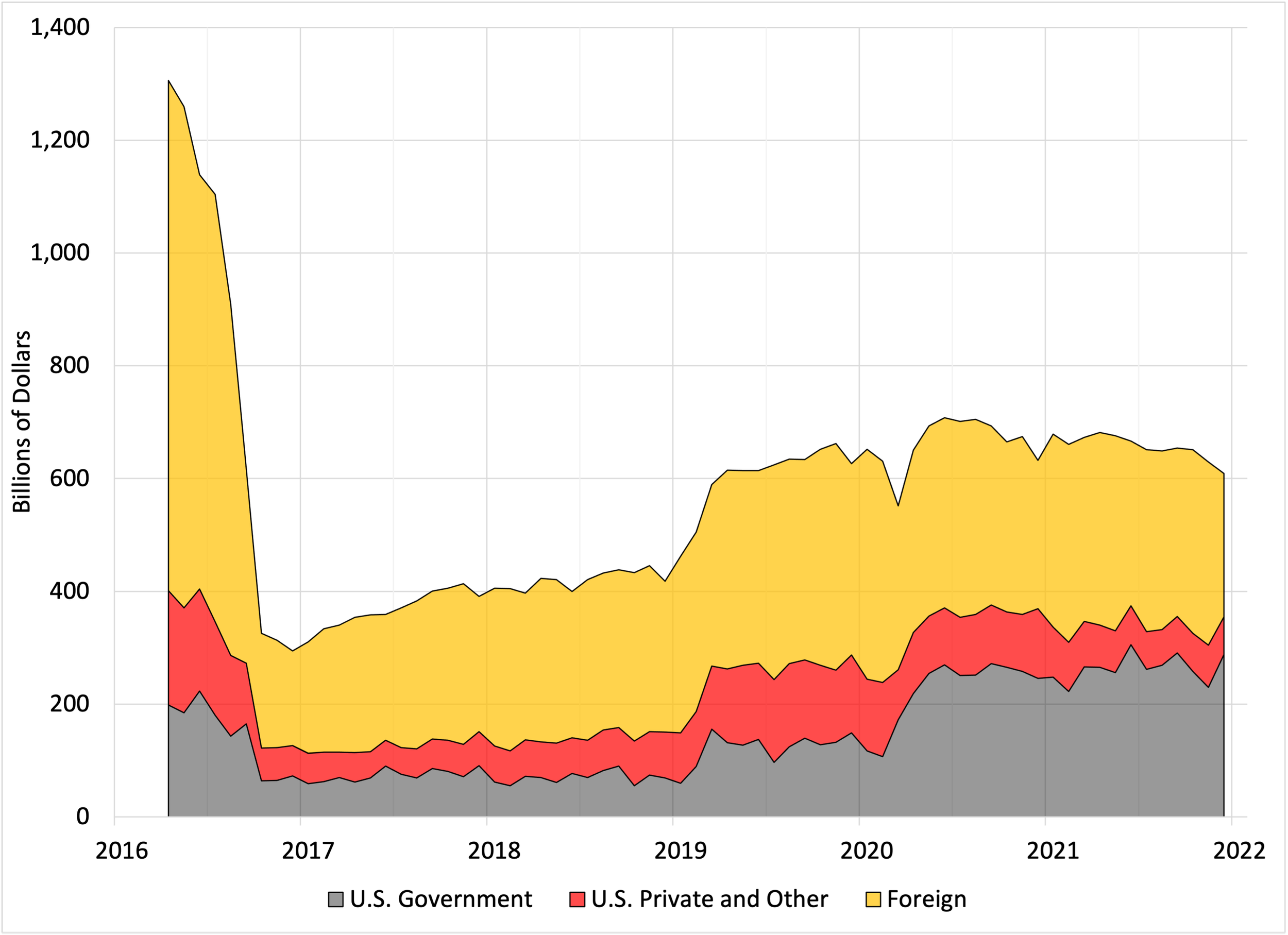

Importantly, the previous chart understates the shift to safety in the composition of MMMFs. To see this, we plot below the details of prime institutional funds’ holdings. At the end of 2021, government instruments (in gray) accounted for $288 billion—a whopping 81%—of prime institutional funds’ $355 billion in U.S. assets. As a result, these MMMFs invest a negligible $61 billion in U.S. private short-term funding instruments (in red). That is, MMMF holdings account for only about 3% of outstanding commercial paper (CP) and large certificates of deposit (CD) issued by U.S. entities. At the same time, however, prime institutional funds provide substantial short-term finance to foreign (mostly financial) borrowers (in yellow). While we do not show it on the chart, $168 billion of the $254 billion in foreign assets at the end of 2021 are accounted for by the liabilities of Canadian, Japanese, French, and Australian financial intermediaries. So, U.S. prime institutional MMMFs probably remain a potential source of systemic risk to financial systems elsewhere in the world.

Assets of U.S. prime institutional MMMFs (Billions of Dollars), April 2016-December 2021

Source: Office of Financial Research U.S. Money Market Fund Monitor.

The SEC proposals. Turning to their 325-page December report, the SEC provides a largely qualitative discussion of the PWG’s MMMF reform proposals, endorsing several and rejecting others. For the most part, their reform proposals focus on the floating-NAV funds, especially the prime institutional funds that experienced the largest outflows in the March 2020 episode.

The SEC endorses the following three reforms:

Liquidity Fees and Gates. Removal of optional liquidity fees and redemption gates for non-government funds (reversing the 2014 reform).

Swing Pricing. Requiring swing pricing for floating-NAV prime institutional and tax-exempt funds.

Portfolio liquidity requirements. Raising daily liquidity asset (DLA) requirements from 10% to 25% of assets and weekly liquidity asset (WLA) requirements from 30% to 50% of assets.

The SEC argues that each of these would mitigate the first-mover advantage, thereby reducing the likelihood of runs. We agree that fees and gates were damaging, but are concerned about the operational challenges of implementing swing pricing and doubt that the new liquidity requirements are properly calibrated.

Fees and Gates. The SEC reform of 2014 allowed funds the option to impose such liquidity restrictions once a fund’s weekly liquid assets (WLA) fell below 30%. Following the 2020 crisis, researchers have found compelling evidence that these liquidity rules exacerbated the runs on prime funds as their WLA declined (see Li et al). This vulnerability should have come as no surprise, so the proposal to remove these optional restrictions is surely welcome (for details on pre-2014 criticism of the SEC’s fees and gates options, see our earlier post).

Swing pricing. Research on U.K. bond funds concludes that swing pricing reduces first-mover advantage and the risk of runs (see Jin et al). Very briefly, swing pricing adjusts the price (NAV) at which aggregate transactions settle to place the burden of transactions costs on those redeeming their shares rather than on remaining shareholders.

As the SEC claims, swing pricing ought to reduce first-mover advantage in funds holding illiquid assets, including MMMFs that hold commercial paper, bank CDs, or municipal debt (see our earlier post). However, the fund industry warns that due both to the time needed to estimate the swing factor and to the fact that some funds set their NAV more than once a day, implementation would be operationally challenging for U.S. MMMFs (see, for example, the ICI comment, page 20). So, while the introduction of swing pricing might be helpful, we are cautious about relying on it as the principal (and virtually sole) means to improve resilience of MMMFs.

Portfolio liquidity requirements. The SEC proposes raising MMMF portfolio daily liquidity asset (DLA) requirements from 10% to 25% of assets and weekly liquidity asset (WLA) requirements from 30% to 50% of assets. While we agree that this is a step in the right direction, our conclusion is that the increase is seriously inadequate for at least two reasons. First, the new requirements fall well short of recent norms in the prime institutional fund industry, which reported average DLA (WLA) shares of 53% (63%) at the end of 2021 (see Tables 7 and 8 here).

More importantly, the SEC calibrates the new requirements using data from March 2020, when the largest weekly outflow was around 55% and the largest daily outflow was about 26%. We are struck by the implication that a requirement designed to reduce run risk would be based on net redemption patterns during the exact period when Fed intervened to backstop the entire financial system.

If the goal is to set prime institutional MMMF liquidity requirements sufficiently high to avoid the need for special central bank support, the episode of March 2020 is an outrageously inappropriate benchmark. Yet, the SEC’s liquidity requirement modeling relies specifically on the “distribution of redemptions from 42 institutional prime funds observed during the week of March 16 to 20, 2020.” Remarkably, even applying this weak test, Figure 14 in the SEC analysis (page 212) shows that about 8% of prime institutional funds (based on our interpolation of the chart) would have run out of DLA on at least one day that week. For comparison, imagine the systemic consequences if 8% of commercial banks were forced to sell illiquid assets in a stressed week to meet deposit withdrawals.

Shouldn’t MMMF liquidity requirements be set to ensure that all prime institutional MMMFs can withstand a high-stress period without reliance on public support?

What’s missing from the SEC proposals? Finally, we highlight two elements we believe to be missing from the proposed reforms: the imposition of risk-adjusted capital requirements and the enhancement of stress tests.

Capital requirements. Analysts have long proposed risk-adjusted capital requirements as a device to make risky MMMFs safer. For example, the Squam Lake Group in 2013 identified a capital buffer as its preferred approach for regulating prime MMMFs. More recently, the Systemic Risk Council argued that “funds and other vehicles with access to Federal Reserve liquidity insurance need to be required to issue capital instruments of some kind that will absorb losses ahead of those investor claims that rely upon being liquid and safe.” Operationalizing the capital buffer by adding a loss-bearing, subordinated class of liabilities would not require changing the structure of current MMMF shares but would make them less risky as senior liabilities. (We do not discuss the “minimum balance at risk”—MBR—alternative to capital requirements primarily because it would weaken the cash-management feature of MMMFs while posing operational challenges.)

Economists have previously estimated the costs of imposing risk-adjusted capital requirements on MMMFs. Importantly, it makes no sense to claim (as some capital requirement opponents do) that MMMFs are safe while simultaneously arguing that capital requirements would make them unviable. Precisely because MMMFs generally perform less liquidity, credit and maturity transformation than banks, the necessary risk-adjusted capital buffers to achieve bank-level resilience ought to be relatively small. Using a bank safety standard, Hanson, Scharfstein and Sunderam (HSS) conclude that a capital requirement of 3 to 4 percent of unsecured, non-government assets would be reasonable for prime institutional MMMFs. They then go on to estimate that this would depress the return to ordinary MMMF shareholders by only 5 basis points. Similarly, former SEC chief economist Lewis reckons the necessary capital buffer for a well-diversified MMMF at only 0.6% of total assets, implying an even lower cost to ordinary MMMF shareholders (see here).

Against this background, the 2021 SEC report provides a relatively brief qualitative discussion of the pros and cons of capital requirements, with the latter including operational challenges, uncertainty about the opportunity cost of the required capital, the reduced willingness of MMMFs to hold riskier short-term private debt, and the potential for heightened redemption if the buffer becomes impaired. The report then concludes that “capital buffers may not have the same benefit for investment products such as money market funds, where the investors bear the risk of loss, as they do for banks” (page 258).

In our view, this conclusion is directly contrary to the facts. Precisely because of prime institutional funds’ systemic importance for short-term financial markets (especially for the dollar funding of foreign banks), the Federal Reserve has felt compelled to backstop MMMFs twice since 2008, and would almost surely do so again tomorrow if there were another funding crisis.

Against this background, three of the SEC’s arguments against capital requirements appear to us to be features, not flaws. First, if capital requirements prompt MMMF managers to reduce their holdings of risky short-term private debt, it is because the requirements compelled them to internalize the spillovers their actions have on other parts of the financial system. Second, it ought not be too difficult to estimate the cost of capital involved. In fact, HSS did it by exploiting the similarity between the risk of MMMF losses and the default risk on bonds issued by financial firms. Third, if an MMMF should experience losses, the incentive for shareholders to run must be lower in the presence of a capital buffer than it would be without one.

Finally, the SEC offers no evidence that the operational challenges of establishing a capital buffer would be greater than the challenges of introducing swing pricing.

Enhancing stress tests. Beginning in 2010, the SEC required MMMFs to implement stress tests. They enhanced the testing requirement in 2014, so that today MMMFs must periodically assess the impact on their asset liquidity of scenarios that assume increases in short-term interest rates, credit events, and wider credit spreads, along with various levels of redemptions (see also Berkowitz).

Even today, however, the SEC stress testing regime does not conform with basic principles of effective stress testing: namely, transparency, severity and flexibility (see our earlier post). First, to impose effective market discipline, the scenarios must be sufficiently consistent in form and substance to facilitate comparison of the results and the individual results must be published. However, the current regime provides no such transparency for MMMFs. Not only are the results unpublished, but we do not even know whether the stress test scenarios are comparable across funds.

Lacking such transparency, there also is no way to judge whether the stress tests are adequately severe to detect MMMF vulnerabilities. And there is no way to know whether the hypothetical scenarios are evolving sufficiently to ensure their continued relevance (as financial conditions change) and to prevent stress test gaming.

Given the SEC’s support for the use of stress testing in risk management, we are at a loss to explain these fundamental flaws in the MMMF stress testing regime. We can only hope that the SEC will revisit this issue and make high-quality stress testing a key part of enhancing MMMF resilience going forward.

Conclusion. To conclude, we are profoundly disappointed. The SEC is once again missing an opportunity to implement desperately needed reforms in the regulation of MMMFs. While the proposal to eliminate voluntary liquidity fees and gates is laudable, and the introduction of a workable swing pricing regime would be helpful, these actions alone likely would not put an end to government bailouts of MMMFs. It is well past the time for MMMFs to face risk-adjusted capital requirements, realistically calibrated liquidity requirements, and credible stress tests.

Acknowledgements: Without implicating either of them, we thank our friends, NYU Stern Professor Richard Berner and Sir Paul Tucker, for helpful discussions regarding MMMF regulation.