Central Banks' New Frontier: Interventions in Securities Markets

“[T]he infrastructure built up within central banks to assess and manage collateral during the crisis should be maintained as a permanent feature. This feature is already part of the regular operations of the Bank of England and the Reserve Bank of Australia.” Mervyn King, The End of Alchemy, pg. 275.

In his 2016 book, The End of Alchemy, our friend and former Bank of England Governor Mervyn King provided a template for financial reform aimed at reducing the frequency and severity of crises. At the time, we were very cautious for two reasons. First, we believed that adoption of King’s framework would vastly increase the influence of central banks on financial markets, something that could ultimately lead to a misallocation of resources in the economy and to a diminution of the independence of monetary policy that is necessary for securing price stability. Second, we doubted that most central banks had the technical capacity to implement the proposal.

Well, the landscape has changed significantly. During the pandemic, central banks intervened massively in securities markets and there now appears to be no turning back. In a number of jurisdictions, monetary policymakers broadened the scale and scope of their lending and intervened directly in financial markets, going significantly beyond even their extraordinary actions during the 2007-09 financial crisis. As a result, we likely will be paying the costs that we feared could accompany the implementation of King’s proposal, so we might as well reap the benefits.

In this post, we discuss central banks’ pandemic interventions and the type of infrastructure needed to support them. We then review King’s proposal, highlighting how adopting his approach would make the financial system safer, while radically simplifying the role of regulators and supervisors.

Turning to central banks’ pandemic responses, in their survey of 39 jurisdictions, the BIS reports that 21 purchased some form of public assets and 13 purchased assets from private issuers, while all engaged in extraordinary lending operations. Indeed, there were 144 such lending programs, including 36 repo facilities and 16 programs targeting small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

To be sure, this is not the first time that central banks intervened in markets for assets from private issuers. Notable examples include the Hong Kong Monetary Authority’s (HKMA) purchase of equities in 1998 and the Bank of Japan’s ongoing purchases of exchange traded funds (ETFs) that began in 2010. Indeed, the Bank of Japan, which now owns more than five percent of the market value of listed stocks, appears to have lowered Japan’s equity risk premium in an economically significant way (see Katagiri, Takahashi and Shino).

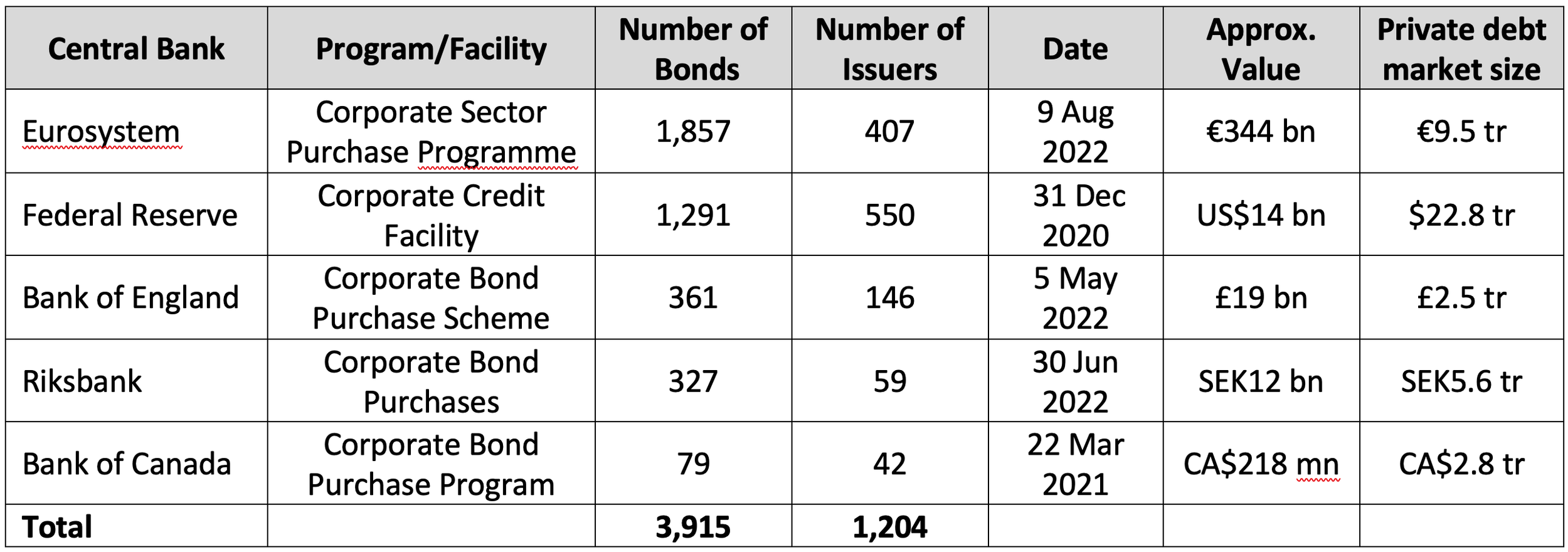

Nevertheless, the scale and scope of the recent pandemic purchases constitutes a major shift from previously accepted practice. The following table reports some notable characteristics of interventions in corporate bond markets by five central banks for which data are readily available. With exception of the Eurosystem’s corporate sector purchase program (CSPP), which operated intermittently since June 2016 and is by far the largest, these all began in 2020.

Central bank purchases of corporate bonds

Notes: In addition to individual corporate bonds, the Federal Reserve also purchased 16 different bond ETFs that are included in the approximate value. The Eurosystem totals do not include the €43bn of corporate bonds as a part of its pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP). The private debt market size as of 3Q 2021 is from the BIS debt securities statistics, converted to local currency using then-prevailing average exchange rates. It includes financial and nonfinancial corporate issues outstanding. Sources: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve, European Central Bank, Bank of England, Sveriges Riksbank, and Bank of Canada.

Looking at this table, we see that these five central banks purchased nearly 4,000 separate bonds issued by 1,200 firms. With the notable exception of the Eurosystem, the amounts were quite small. Even so, there is evidence that they were effective in stabilizing markets, in part because of the perceived willingness to purchase far more as needed (see Gilchrist, Wei, and Zakrajšek for a discussion of the U.S. case).

As an operational matter, when a central bank either takes a security as collateral for a loan or purchases the security outright, it must take a view regarding the fair market value of the security. Pricing accuracy is more important for outright purchases than for loans, where a haircut can be applied to the collateral to account for market risk. So, outright purchases create an even heavier modeling burden. Nevertheless, in both cases, a central bank must have an infrastructure for pricing and risk management.

The extensive interventions during the pandemic required just such an infrastructure. Focusing on the Eurosystem and the Federal Reserve, we know that they have various risk management mechanisms in place. For collateral, there are processes for establishing a list of what is eligible, setting haircuts, and agreeing on the value of the securities to be posted. Furthermore, these two large central banks have pricing models that allow them to produce independent estimates of fair value.

To see what we mean, consider the Eurosystem’s collateral framework. To obtain credit through the various refinancing facilities—main, long term, targeted long term, and so on—banks can deliver any of the more than 25,000 securities included on the public list, which is updated daily. Furthermore, banks can request the addition of specific securities that do not appear on the current list!

Importantly, the Eurosystem’s collateral list includes many highly illiquid instruments. As Bindseil et al report, in September 2015, 85% of the 34,389 eligible securities never traded, and another 8% traded 10 or fewer times during that month. This means that it is impossible to use market prices to establish value for more than a small fraction of these securities. In lieu of this, “[t]he Eurosystem assigns a price to each marketable asset on a daily basis through its ‘Common Eurosystem Pricing Hub’ (CEPH) [….] The high share of asset prices based on theoretical valuation rather than on market prices reflects the fact that a large proportion of the fixed income universe trades infrequently.” (Bindseil et al pg. 56).

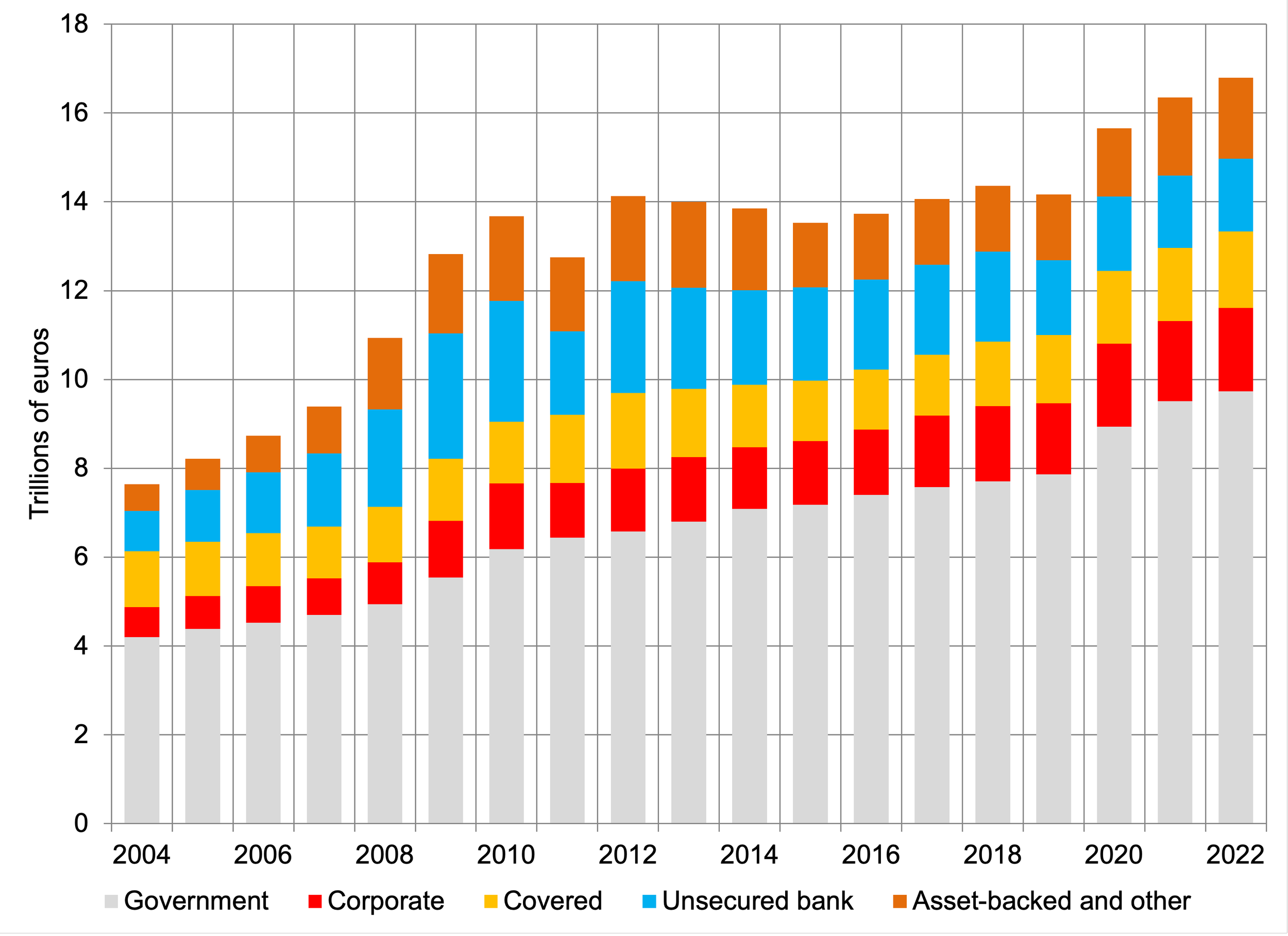

The following chart displays the distribution of different types of bonds that are eligible to serve as Eurosystem collateral. The total currently exceeds €16 trillion, or 50% of total euro-area banking system assets. Of these, a bit more than one-half are government securities, while 10 percent are corporate bonds.

Eurosystem Collateral Framework Eligible Assets, 2004 to 1H 2022

Notes: Amounts are end-of-month averages for each the fourth quarter of each year. Data for 2022 are midyear. “Government” is the sum of central and regional government issues. Source: ECB.

The case of the Federal Reserve is somewhat different. Unlike the Eurosystem, with its historical focus on providing reserves through its lending (or refinancing) facilities, the Fed supplies reserves primarily by purchasing securities. The U.S. central bank is authorized to own only federally guaranteed securities, which must be acquired in secondary markets. In response to crises, however, the Fed creates captive entities to which it lends for the purpose of buying securities of private issuers or making certain types of loans. Even this “indirect” acquisition requires the evaluation of collateral and determination of prices to ensure that the central bank is not providing funding to insolvent entities.

Turning to a few specifics, in the case of discount loans, the Fed publishes a list of collateral it will accept, combined with haircuts that it will apply: there are roughly three dozen types of securities, each with a haircut that depends on maturity. U.S. practices differ significantly from those in the euro area. As the Fed states: “Securities are valued using prices supplied by the Federal Reserve’s external vendors. Securities for which a price is unavailable from external vendors will receive zero collateral value.” It is not clear how the Fed’s vendors decide which assets to price or how they regularly price instruments that never trade.

To continue, consider the Corporate Credit Facility (CCF) listed in the previous table. For the CCF, the Fed engaged BlackRock Financial Markets Advisory as the investment manager. The Fed also published a list of firms from which they were willing to purchase the securities. When the purchases occurred, they appear to have been executed at prevailing market prices (see here and here).

Based on these practices, one might think that the Fed does not have a dedicated internal infrastructure for valuing either potential collateral for loans or securities that it might purchase outright. Yet, as part of the process supporting the comprehensive capital assessment review (CCAR)—the annual stress test for the largest U.S. banks—the Fed has an elaborate system for estimating the fair-market pricing of securities and loans. Indeed, in constructing CCAR stress scenarios, the Fed provides risk prices for a very broad array of assets that banks might hold (see here). The authorities could not compute these risk prices without models that establish fair value in normal times.

Based on these ECB and Fed practices, it is fair to conclude that interventions by both central banks during the pandemic were supported by frameworks for valuing collateral used to back loans and for pricing securities purchased outright. In some cases, the modelling and risk management expertise was internal to the central bank, while in others private firms supplied the necessary tools. Regardless, authorities clearly know how to manage the risk of interventions in markets for assets of private issuers when they so wish.

Going forward, unless legislatures change the rules that govern them, central bankers who intervened twice in a dozen years to rescue financial markets cannot credibly claim that they will avoid doing so in a future crisis. Market participants’ awareness that they will intervene unavoidably leads to mispricing. For example, both funding and liquidity risk probably are underpriced today because everyone anticipates that the central banks will provide a crisis backstop.

Can we minimize the damage?

This brings us back to former Governor King’s proposal to make the financial system safe. Ultimately, the conversion of a central bank into King’s pawnbroker for all seasons (PFAS) could substitute for today’s complex government safety net (including deposit insurance and the lender of last resort).

How does the PFAS work? Under the King framework, any fixed-value liability issued by a financial institution that has short maturity (say, less than one year) must be 100%-backed by acceptable collateral posted with the central bank at a pre-determined haircut. To avoid shifting risk out of the banking system, this collateral rule applies to any financial entity. Because of the haircuts, the face value of the collateral will exceed the level of demand deposits and any other short-term liabilities. Critically, the PFAS commits to provide access to liquidity—up to the haircut value of the collateral—through its lending facility in both good times and bad. Put differently, the central bank will always be there to ensure the liquidity of the financial system’s short-term fixed-value liabilities.

The PFAS framework is both extremely simple and quite powerful. It is a hybrid between the current financial system and one with narrow banks. In the narrow bank world, reserves at the central bank must be greater than or equal to the level of demand deposits. Put differently, these deposits cannot be used to finance risky assets. Under current bank regulation, required reserves are far smaller than deposits: in the United States, they are zero. King’s scheme is between these two, as the sum of haircut loans and securities posted for collateral must exceed the level of all short-term liabilities of financial entities, including but not limited to demand deposits at banks.

In our view, the PFAS approach has many of the advantages of narrow banking (including dramatic simplification of capital requirements and possible elimination of deposit insurance), without the serious disadvantage of driving risky lending out of the regulated system (see our earlier posts here and here).

As we noted at the beginning of this post, we were originally doubtful about the PFAS. Five years ago, our concern was that the central banks, through their haircut policies, would distort the composition of commercial banks’ balance sheets. Since securities and loans with modest haircuts will be cheaper to fund, the central bank’s haircut policy will determine the relative desirability of funding different borrowers. We fear that such broad intervention by the central bank eventually will invite political interference in the allocation of credit, reducing the efficiency both of markets and of resource use. It also may weaken the willingness of legislatures to support the independence that central banks need to make monetary policy effective in keeping inflation low and stable.

Yet, regardless of what we or anyone else might think, the central banks are now engaging in broad intervention or are widely expected to do so during any serious episode of financial instability. Moreover, there seems to be little legislative willingness to rein in the scope of central bank intervention. Fortunately, at least, central banks now have the analytical capacity (internally or externally) to limit the market risk they accept. That is, they can estimate the fair market value for a broad range of securities of private issuers.

So, why not take advantage of King’s approach to make our financial system safer and simplify the regulatory framework?