The Future of Deposit Insurance

This post is authored jointly with our friend and colleague, Thomas Philippon, Max L. Heine Professor of Finance at the NYU Stern School of Business.

Deposit insurance is a key regulatory tool for limiting bank runs and panics. In the United States, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) has insured bank deposits since 1934. FDIC-insured deposits are protected by a credible government guarantee, so there is little incentive to run.

However, deposit insurance creates moral hazard. By eliminating the incentive of depositors to monitor their banks, it encourages bank managers to rely on low-cost insured deposits to fund risky activities. In the extreme, with 100% deposit insurance coverage, banks would have virtually no incentive to issue equity or debt. Not surprisingly, U.S. banks today are far more levered (with an average assets-to-capital ratio around 10:1) than they were in the 1920s (about 4:1), prior to the government provision of deposit insurance.

In practice, no country explicitly promises 100% deposit insurance. The principal reason is to limit the moral hazard problem. Capping deposit insurance—and keeping open the possibility that some deposits will remain uninsured even in a crisis—can impose some discipline both on the largest depositors and on their banks.

A second reason to limit deposit insurance coverage is to control the public cost of the guarantee. Looking at the case of the United States, at the end of 2022, depositories had $19.2 trillion of deposits. Roughly one-half of these, an estimated $10.1 trillion, were insured. In the absence of other changes, the introduction of 100% deposit insurance would encourage even greater reliance on deposit finance and expose the FDIC’s deposit insurance fund to larger losses—losses that are ultimately backstopped by taxpayers.

In crises, however, policymakers often opt to backstop all deposits even in the absence of a legal obligation. In 2008, the FDIC guaranteed all fixed liabilities of U.S. banks. In March 2023, they protected all the deposits of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank. In May 2023, they entered into a “purchase and assumption” sale of First Republic that made all its depositors whole, too. If, in a crisis, the authorities have an option to provide coverage beyond what is explicitly insured, their inability to commit credibly not to do so encourages risky behavior on the part of those with implicit protection.

The following chart highlights key episodes of FDIC history: it shows annually the number of bank failures (gray shading) and the inflation-adjusted losses sustained by the deposit insurance fund (red line). Both the savings and loan crisis (late 1980s and early 1990s) and the 2007-09 financial crisis stand out. Notably, as of May 1, estimated 2023 losses surpassed the previous annual record.

Bank failures and FDIC Deposit Insurance Fund (DIF) losses (in 2022 dollars), annually, 1934-2023E

Note: The dashed line red line is an estimate (as of May 1, 2023) of the 2023 losses of the deposit insurance fund based solely on the expected resolution costs of First Republic, Silicon Valley and Signature banks. Losses are deflated using the PCE chained price index (2022=100).

Sources: FDIC 2022 Annual Report, FRED and authors’ 2023 estimate.

Against this background, and in light of the events of March-April 2023, we ask what is to be done about deposit insurance. To prevent bank runs, should there be an increase in the legal limit? If so, how can authorities balance the costs of runs and panics against the costs associated with moral hazard, while keeping in mind the potential financial burden on the public? Or, are there alternatives?

We emphasize three promising ways to enhance deposit insurance: a higher insurance cap for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), new resolution rules, and the option to purchase supplementary deposit insurance. In addition, and as regular readers of this blog might expect, we also think that higher capital requirements should be part of the solution: if we require that banks increase the degree to which they finance their assets with capital (rather than deposits), the risk of runs and panics would decline even without raising the cap on deposit insurance.

From this perspective, the current cap of $250,000 per account appears more than sufficient for the transaction needs of most households and businesses. According to the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finance, for all families, the median (mean) holdings of transaction accounts were only $5,300 ($41,600). Even for the top 10% of households ranked by income, the median (mean) holdings were only $70,000 ($229,000).

Looking beyond households to a broader sample, information in the bank’s regulatory disclosures (known as the call reports) reveals that less than 1% of all deposit accounts (excluding retirement accounts) have balances in excess of $250,000. Furthermore, more than one-half of these are held at the largest 13 banks. Similarly, a survey of the 2015 transactions of 597,000 small businesses shows that the median cash balance was only $12,100, equivalent to 27 days of average outflows (see here).

Nevertheless, the events at Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) highlight the spillovers that a bank run can have on SMEs which use their transaction deposits to meet payroll and other operational costs. For example, in 2020 there were 245,000 medium-sized firms (50 to 5,000 employees) that employed 52 million people and supported an annual payroll of almost $3 trillion. Even if only one-tenth of these firms had weekly transactions exceeding $250,000, the broader consequences of their bank accounts becoming inaccessible for a few days could be substantial. This alone suggests that there is justification for exploring the benefits of raising the deposit cap for small and medium-sized businesses (SMEs) to ensure that most firms can meet their weekly (or perhaps monthly) transaction needs using insured deposits.

We note that deposit brokers already make it feasible for businesses to insure far more than $250,000 in transactions accounts by distributing the funds across numerous banks (see, for example, IntraFi). From a policy perspective, however, this kind of deposit-insurance arbitrage is opaque, and (as the runs on SVB and Signature Bank reveal) may not be understood by small firms that lack professional cash managers. Consequently, if policymakers choose to raise the insurance cap for SMEs in a transparent way, they also should restrict the existing deposit-broking arbitrage.

In the aftermath of the recent bank failures and resolutions, the FDIC needs to reconsider both the level and risk-sensitivity of its insurance assessments. The goal should be to ensure that fees are actuarially fair across banks and sufficient to sustain the Deposit Insurance Fund (DIF) on average over the long run without relying on taxpayer contributions (see our earlier post).

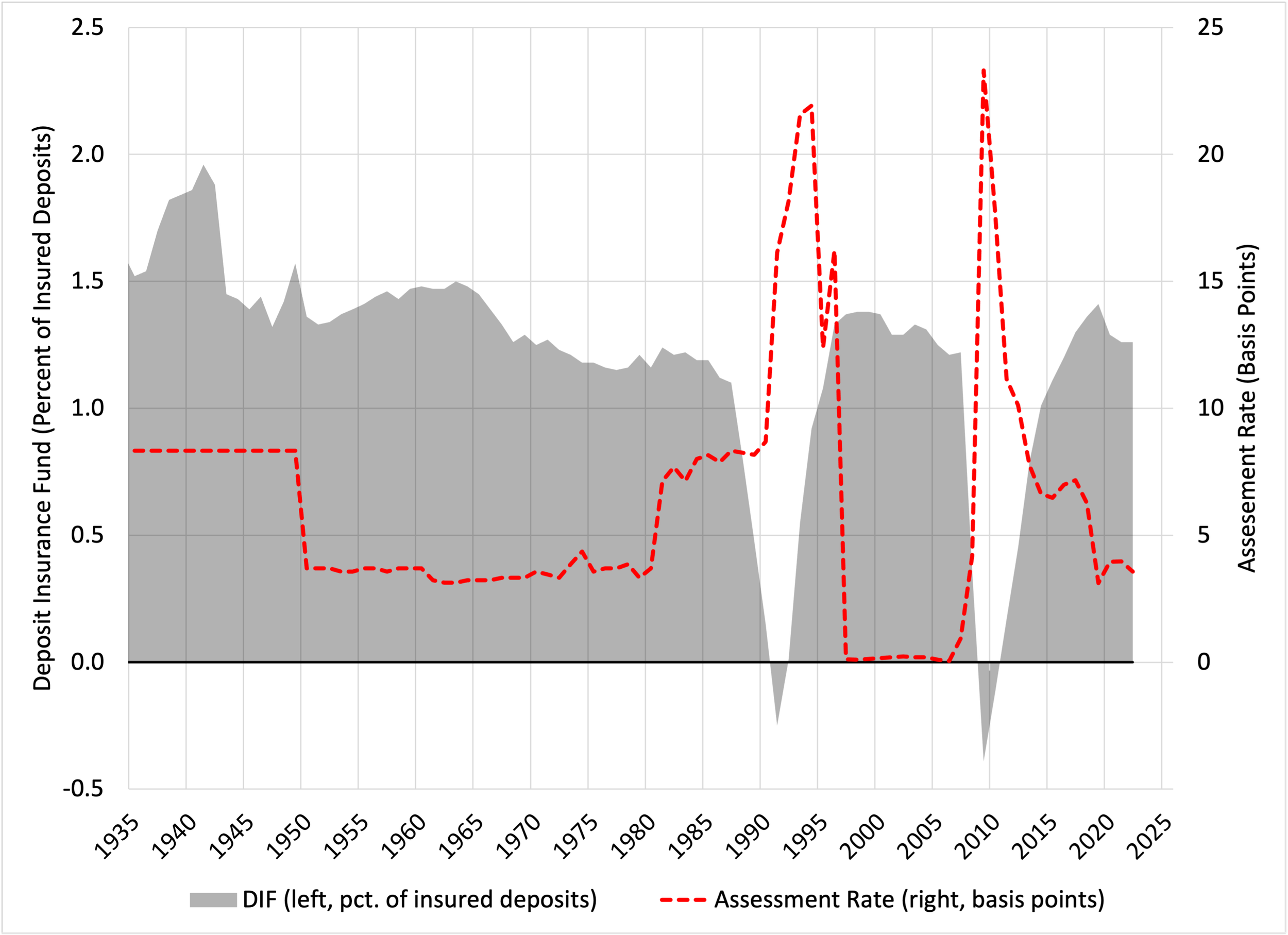

An essential part of such a redesign should be to make the assessment rate more stable through the cycle. The following figure shows the effective bank assessment rate (in red) and the balance of the deposit insurance fund as a percentage of insured deposits (in gray). Rather than maintaining a steady premium, the fees exhibit enormous procyclicality. In good times, when there are few failures, the insurance fund balance is relatively high, and the assessment rate is cut to an unsustainably low level. When a crisis occurs, the insurance fund balance plunges, and the assessment rate temporarily skyrockets. These fluctuations create awful incentives: by “taxing the survivors,” the FDIC’s post-crisis fees compel well-run firms to bear the costs of resolving those poorly managed institutions that failed. Over time, such penalties can encourage a race to the bottom among banks.

Deposit Insurance Fund Balance and Effective Assessment Rate, 1935-2022

Source: FDIC 2022 Annual Report.

Aside from raising the deposit insurance cap for SMEs, authorities may wish to consider other policy options to reduce the likelihood and cost of bank runs. For example, resolution rules that both assure the continued operation of the bank and prioritize SME transaction accounts could limit the spillover effects of a bank run. Another possibility is for the deposit insurer to offer banks an option to increase the insurance cap for an additional risk-based fee. Some mix of these three tools (higher insurance cap for SMEs, new resolution rules, and supplementary deposit insurance) could help balance run risks and moral hazard costs better than implementing any one of them. Such changes also would make it easier for policymakers to avoid doing what they did both in 2008 and 2023: namely, backstop uninsured bank liabilities.

Yet another possibility is to impose a minimum balance at risk (MBR) requirement on uninsured deposits that are deemed to be at high risk of running. In such a scheme, a fraction of an uninsured deposit would be unavailable to the depositor for some period (say, 30 days), and could help absorb losses should the bank fail. In effect, a portion of every uninsured deposit becomes contingent capital that can only be withdrawn if the bank survives for a predetermined length of time. Put differently, an MBR compels those that withdraw early to bear at least some of the losses that their actions impose on more patient depositors. However, an MBR has two potential drawbacks. First, by making seniority dependent on past transactions, it is complex to administer. Second, it would compel all depositors with large gross flows through their deposit accounts to hold sizable idle balances, making them de facto equity holders without the usual privileges of such ownership.

To limit the future call on deposit insurance, it is essential that other policies be reformed as well. Above all, U.S. regulators need to increase capital requirements. The 2023 runs on midsized banks show that these banks (and probably many others) were severely undercapitalized. Bank capital is a form of self-insurance. The better a bank’s capitalization, the lower the incentive of depositors to run. And, if policymakers wish to increase the cap on deposit insurance, which is habitually underpriced, the increased risk coverage should be accompanied by an increase in self-insurance. Finally, in contrast to an MBR, which makes all depositors quasi-equity holders, greater reliance on common equity funding distributes the bank’s residual risk only to those who choose to bear it. (As we noted in an earlier post, higher bank capital also has the added advantage that it results in more lending to high quality borrowers.)

In practice, banks’ fierce opposition to sufficiently high levels of capital makes it essential that policymakers also explore other (potentially second-best) ways of limiting calls on deposit insurance. Properly structured liquidity requirements are one such possibility. To see how improving liquidity rules can matter, consider that SVB’s failure resulted from the combination of two big mistakes: on the asset side, it undertook massive interest rate risk; on the liability side, it funded these assets principally by issuing extremely runnable uninsured deposits. (See our earlier post for a detailed discussion of the failure of SVB.) It ought not be difficult to re-calibrate the parameters of the Basel III liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) to ensure that it both flags and penalizes such an unstable mix. For example, by sharply increasing the assumed response of deposit outflows in the presence of such mismanagement, a recalibrated LCR would compel banks to adopt a more stable asset-liability mix.

Importantly, some liquidity problems may require tools other than deposit insurance and liquidity coverage ratios. For example, some payment service providers (PSPs) use uninsured deposits to manage their day-to-day liquidity needs (see here). Yet, even a bank’s “high quality liquid assets”—which can include illiquid securities—seem inadequate to meet the immediacy needs of such PSPs. Consequently, their use of uninsured deposits adds massively to the potential spillover effects of a run. To manage this systemic risk, we support the creation of a special regime for PSPs’ transaction accounts, requiring that they be 100% backed by reserves held at the central bank.

Before concluding we note that deposit insurance should not be used as an instrument for altering the competitive position of inefficient banks that lack sufficient economies of scale. To be sure, we share the widely-held concern that “too big to fail” banks benefit from an implicit government guarantee that lowers their funding costs. However, there is a simple, direct way to limit this implicit subsidy: raise capital (or self-insurance) requirements on the largest banks. A sufficient level of equity finance would compel these mega-banks to internalize the large adverse spillovers that they would cause should they come under stress.

To conclude, recent evidence once again revealed what we have always known: banks with inadequate capital and liquidity fail, placing a burden on the deposit insurance fund and taxing the healthier banks that survive to pay the increased premium needed to replenish it. While deposit insurance plays a useful role in promoting bank stability, we should not lose sight of the key problem in the banking system: namely, the shortfall of capital.

The better the banking system is capitalized, the less that we need deposit insurance to prevent runs and panics. Moreover, unlike deposit insurance, which encourages bank managers to take risks at the expense of taxpayers, increased reliance on equity funding makes the banking system safer by motivating its executives to act prudently.