The Extraordinary Failures Exposed by Silicon Valley Bank's Collapse

“The history of bank regulation in the United States is of progressive dilutions of core regulatory requirements over a number of years, leaving the banking system as a whole vulnerable to crisis.”

Paul Tucker, Chair of The Systemic Risk Council, Letter to Senate Banking Committee leaders, February 21, 2018.

On Friday March 10, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) announced the closure of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB). Banks do fail. From 2011 to 2020, the FDIC closed more than 200 banks. But they were small: all but 10 of the 200 had assets of less than $1 billion, and the biggest was $6 billion. And, there were no runs and no headlines. While the manager, owners, and uninsured depositors knew about the closures, no one else did. SVB really is different.

The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) revealed an extraordinary range of astonishing failures. There was the failure of the bank’s executives to manage the maturity and liquidity risks that are basic to the business of banking: they failed Money and Banking 101. There was the failure of market discipline by investors who either didn’t notice or didn’t care about the fact that the bank was severely undercapitalized for the better part of a year before it collapsed. There was the failure of the supervisors to compel the bank to manage the simplest and most obvious risks. And, there was the failure of the resolution authorities to act in mid-2022 when SVB’s true net worth had sunk far below the minimum threshold for “prompt corrective action.”

Waiting several quarters to act deepened the threat to the financial system, undermining confidence not only in many other banks but also in the competence of the supervisors. The extraordinary rescue actions last week by both the deposit insurer (FDIC) and the lender of last resort (Federal Reserve) are just a sign of the high costs associated with restoring financial stability when confidence plunges.

In the remainder of this post we discuss each of these four failures, as well as the actions that authorities took to stabilize the financial system following the SVB failure. To anticipate our conclusions, we see an urgent need for officials to do at least five things:

First, to regain credibility, supervisors need to do an immediate review of the unrealized losses on the balance sheets of all 45 banks with assets in excess of $50 billion.

Second, they should perform a speedy and focused stress test on each of these banks to assess the impact on their true net worth of a sizable further increase in interest rates. Any bank with a capital shortfall should be compelled either to issue new equity or shut down. (To ensure the availability of the necessary resources, authorities will need to have a pool of public funds available to recapitalize banks that cannot attract private investors.)

Third, to restore resilience, Congress must reverse the 2018-19 weakening of regulation that allowed medium-size banks to escape rigorous capital and liquidity requirements.

Fourth, the authorities must change accounting rules to ensure that reported capital more accurately reflects each bank’s true financial condition.

Finally, policymakers should assess the impact on the financial system and on the federal debt arising from the now-implicit promise to insure all deposits in a crisis. To limit risk taking, correspondingly greater fees and higher capital and liquidity requirements should accompany any explicit increase in the cap on deposit insurance.

To start, recall the principles of banking. In its simplest form, a bank uses a combination of short-term liabilities, long-term borrowing, and equity to finance cash as well as a variety of securities and loans. While every bank has other on- and off-balance sheet assets and liabilities, those are the basics. The business of banking is to transform safe, short-term, liquid liabilities (deposits) into risky, long-term, less liquid assets (loans and securities). A banker’s comparative advantage lies in managing the associated risks through diversification and hedging. Without that, a bank has no franchise.

So much for the basics. Turning to the specifics of SVB risk management, the facts are now well-known. In just three years starting in 2019, SVB tripled its assets from $71 billion to $212 billion. Over 80 percent of its liabilities came from deposits, nearly all of which were large and uninsured. That is, the bank relied to an extraordinary degree on short-term wholesale funding that could easily run. Furthermore, the bulk of SVB customers were part of a tightly connected group of start-up entrepreneurs and their venture capitalists, making the bank highly vulnerable to sudden withdrawals if uncertainty arose regarding its solvency.

On the asset side, SVB held over half of its assets--nearly $120 billion—in a combination of U.S. Treasurys and government-guaranteed mortgage-backed securities (MBS). Importantly, a whopping 85 percent of these bonds had maturity of 10 years or longer. While these are free of default risk, they are not “safe” because their value declines sharply when interest rates rise. In fact, in its most recent SEC filing (10K) for the end of 2022, SVB disclosed that the weighted-average duration of its fixed-income portfolio was 5.6 years. This means that for each 1-percentage-point increase in interest rates across all maturities, SVB would incur losses of 5.6 percent of the value of its portfolio. Not only that, but over the course of 2022, SVB extended the duration of its securities portfolio by nearly 2 full years. That is, as the Federal Reserve aggressively raised interest rates to combat inflation, SVB was increasing its exposure to interest rate risk. They were betting the bank that interest rates would not rise substantially further!

A final aspect of SVB’s balance sheet also is important for this story. Aside from treating securities as trading assets that are always marked to market, banks can choose between two additional ways of accounting for securities that they purchase. They can either classify them as “available for sale” (AFS) or as “held to maturity” (HTM). For all but the largest banks, losses on AFS securities need not affect their profits or their reported net worth (see here). For all banks, HTM securities are accounted for at cost—the price paid to purchase them. Because these securities are not “marked to market,” changes in their market prices have no influence on the reported value of assets or capital.

Of its $117 billion in marketable securities holdings, SVB treated $91 billion as HTM and $26 billion as AFS securities. So, when interest rates rose sharply in 2022, they could keep what was $16 billion in unrealized losses from affecting their reported regulatory capital ratios. (As we discuss below, these losses are disclosed in quarterly and annual SEC filings.)

Putting its asset and liability vulnerabilities together, SVB’s risk management failures are nothing short of breathtaking. Not only that, but press reports indicate that in early 2022 consultants informed the bank’s executives of the inadequacies of their risk management systems. Given the massive erosion of its capital in during 2022, perhaps the shocking thing is that the herd of wholesale depositors did not stampede earlier.

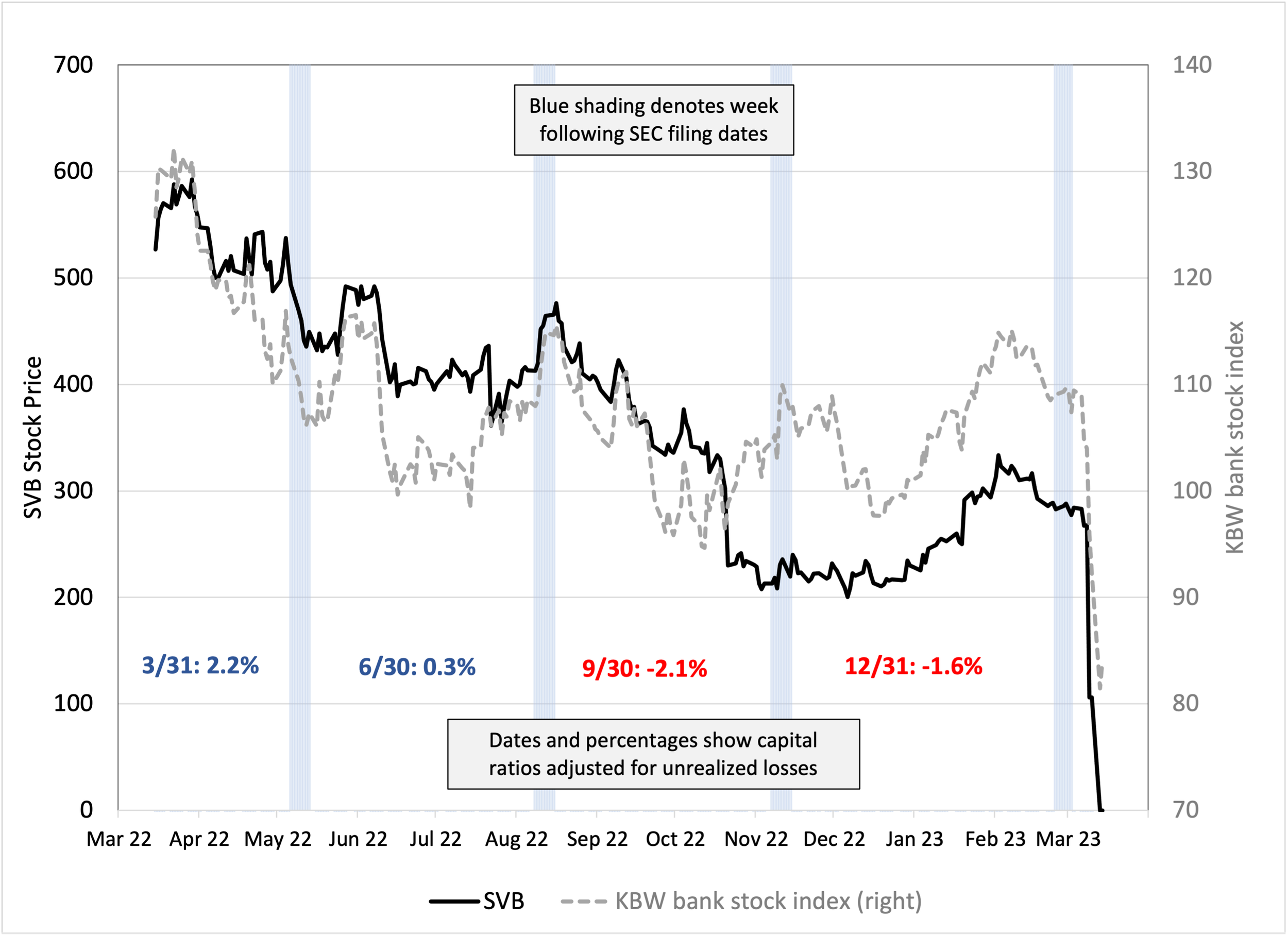

That brings us to the second failure, namely of market discipline. In the following chart, we plot SVB’s stock price (black) and the KBW bank stock index (gray) over the 12 months ending March 10, 2023, when California regulators shut down SVB. The blue shading denotes the week following each of the four quarterly filing dates for SVB’s compulsory SEC disclosures. In the chart, we also report an “adjusted net leverage ratio” at the end of each quarter in 2022. Using SVB’s disclosures, this adjusted measure subtracts SVB’s unrealized capital losses on the total securities portfolio (both AFS and HTM) from a conventional measure of equity (CET1) and then divides by total assets.

SVB Financial equity price and KBW bank index, March 2022 to March 2023

Source: Yahoo finance, SEC, and authors’ calculations.

As the adjusted net leverage ratio figures highlight, SVB’s financial position already was very poor early in 2022, and deteriorated sharply further during the year. At the end of the first quarter, the ratio was just 2.2 percent—substantially below the 5-percent level to that regulators define as “well-capitalized” and the 4-percent regulatory minimum. By the end of the second quarter, that number fell to 0.3 percent. And, by the third quarter, on this measure SVB was insolvent! However, looking at the stock price, it is hard to see any systematic response in the week-long intervals following the damaging disclosures of unrealized losses. Investors either failed to take notice or simply didn’t care. That is, they didn’t care, until suddenly they did!

The third failure is supervisory discipline. Some of this is almost surely a consequence of 2018 changes in the law. As we described at the time (see here), Congress raised the asset size threshold for bank stress tests, liquidity requirements, and resolution plans from $50 billion to $250 billion. In addition, they eased supervision on all but the 15 largest banks. On top of the legal changes, federal regulators used their discretion to relax resolution rules for medium-sized institutions (see here). The consequences of these developments are now obvious: our financial system remains fragile.

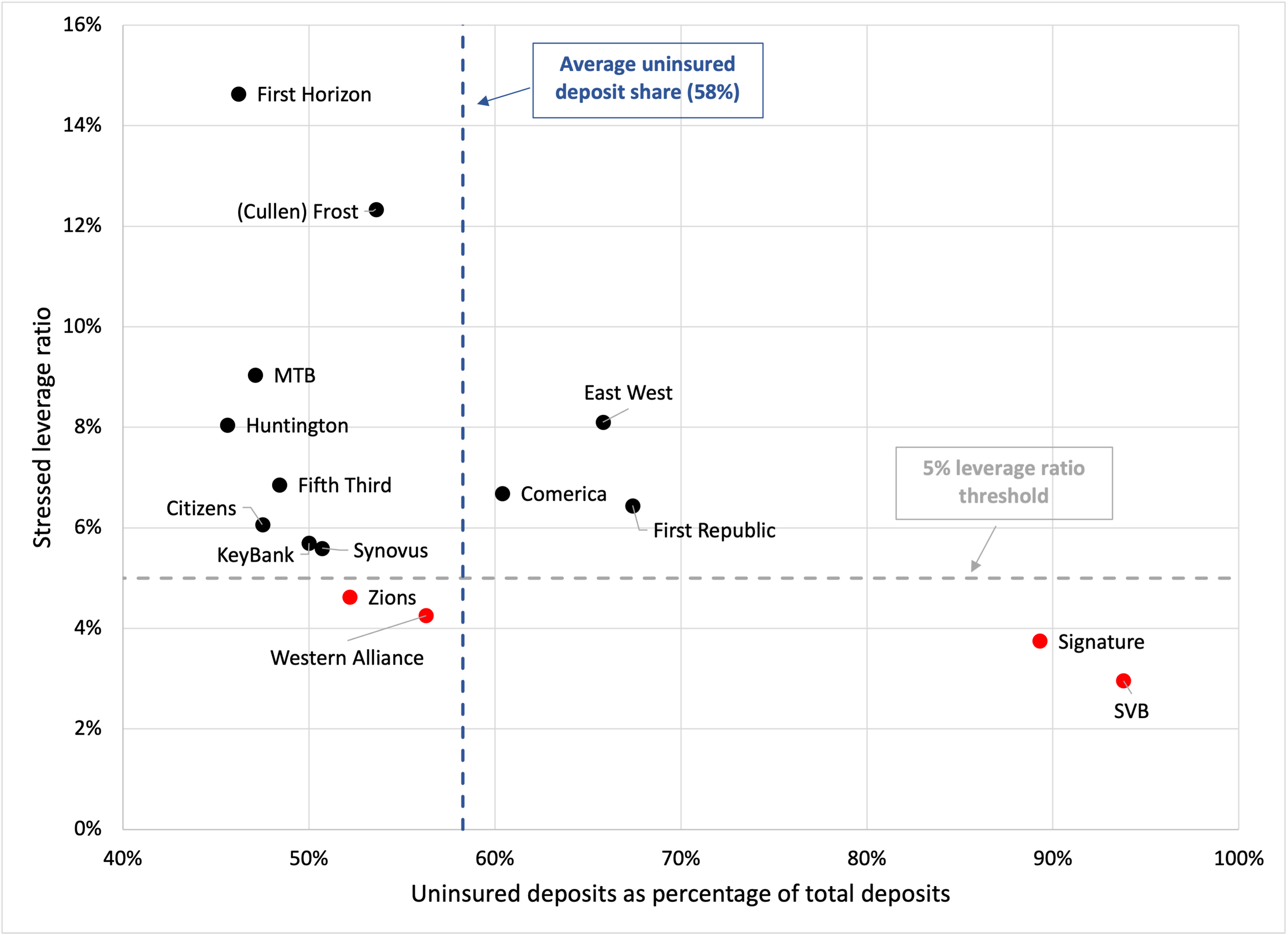

But even a first-class regulatory framework will fail without competent supervisors. In our view, supervisors had virtually costless tools to identify the most fragile banks. To demonstrate this, we conducted a simple experiment based on data that was publicly available. Using the NYU Stern V-Lab's SRISK—a high-frequency, market-based measure of a financial intermediary’s capital shortfall—we ran a simple stress test on publicly-traded medium-sized U.S. banks at the end of 2022. Specifically, we examine the impact on each bank’s leverage ratio of a large (40 percent) decline in the global equity market. (For more on using SRISK as a low-cost stress test, see our earlier posts here, here and here.) We plot the results of this exercise in the following scatter chart: the vertical axis is the stressed leverage ratio (defined in the note below the chart), while the horizontal axis shows the fraction of each bank’s deposits that were uninsured.

Stressed leverage ratio and uninsured deposits, December 2022

Note: For each bank, the stressed leverage ratio is computed as 5 percent times the end-2022 book value of assets minus SRISK, all divided by the book value of assets. This measure differs from the one in the previous chart, which is based entirely on accounting measures in SVB’s SEC filings.

Sources: NYU Stern V-Lab, S&P, and authors’ calculations.

Looking at the chart, we immediately see that SVB and Signature–the banks that regulators closed on March 10 and 12—are outliers in the lower right of the chart (in red). That is, they had stressed leverage ratios–-using market valuations at the end of 2022—of less than 4% of assets, and their deposits were almost entirely uninsured. These data also suggest other banks that face significant challenges. Some, like Western Alliance and Zions, appear undercapitalized, with their stressed leverage ratios below the 5% threshold for being well-capitalized. Others, like First Republic, appear to have only a modest capital cushion and depend significantly on uninsured deposits.

Since the supervisors had access to confidential detailed information about all these banks, we expect that they knew some time ago that Signature and SVB were undercapitalized. However, they took no public actions to remedy the problems. And while reports indicate that Federal Reserve supervisors privately warned SVB about its vulnerabilities as early as 2019, the authorities’ still-undisclosed actions were obviously ineffective in fixing SVB or limiting the fallout from its eventual collapse.

These astonishing supervisory failures undermine trust in the authorities precisely when it is needed most. To regain credibility and make their claims about the strength of the financial system compelling, supervisors will need to act. In our view, they need to introduce extraordinary disclosures, including a bank-by-bank clarification of net worth after full adjustment for unrealized losses and a stress-test measure of each bank’s sensitivity to further interest rate increases. These disclosures also are needed if the Fed is going to be able to pursue safely and consistently its commitment to lower inflation.

Finally, we have two resolution failures. The first occurred in 2022. The FDIC is supposed to shut down a bank when its regulatory capital ratio, measured as tangible equity to total assets, falls below 2 percent. This requirement for prompt correction action is designed to limit the burden of bank resolutions on taxpayers. In our view, supervisors should also force a reckoning if an adjustment for unrealized losses from holding marketable securities would lower regulatory capital below the threshold. That reckoning appears to have waited nearly a full year.

The second failure of supervision is revealed by the decision of the FDIC, in consultation with the Secretary of the Treasury and the President, to invoke the “systemic risk exception” and insure all of SVB and Signature’s depositors, including those with deposits in excess of $250,000. Keep in mind that Congress and the supervisors previously scaled back the rigorous oversight of these banks because, with assets under $250 billion, they were not deemed worthy of the systemic scrutiny imposed on larger banks. Moreover, no one would claim that these two banks alone (with less than 2 percent of U.S. bank assets) posed a danger either to the payment system or to the supply of credit to worthy borrowers (our definition of systemic risk).

Presumably, supervisors feared that a failure to insure all SVB and Signature depositors would lead to a run on other medium-sized banks (like the other fragile ones in the previous chart). If so, however, how could they not have foreseen that as a systemic concern years ago when they downgraded supervisory scrutiny? Moreover, the guardians of financial stability have tools other than deposit insurance: so long as a bank is truly solvent, the Federal Reserve can lend to it at the discount window. This is something the Fed is clearly doing, as lending hit an all-time high of $153 billion during the week ending March 15, 2023 (see here).

So, in our view the events that began on March 10, 2023, revealed four failures: risk management, market discipline, supervision, and resolution. If we are to ensure that our financial system is resilient to future shocks, we need to address all of these as quickly as possible. Importantly, since everyone bears some responsibility, any solution must involve not only public authorities, but private managers and investors as well.

This leads us to underscore the proposals we stated up front. First, authorities should initiate, and banks should demand, an immediate mark-to-market restatement of net worth. Second, each bank should implement and disclose a simple stress test to show the sensitivity of its net worth to higher interest rates. Since they probably already have the necessary information, the healthiest banks should speed the process by immediate disclosures that are subject to public audit. The point is that it is in everyone’s interest to establish now that the medium-sized and large banks are solvent, reducing the risk of further runs and fire sales.

Obviously, such disclosures require that the government have funding available to immediately recapitalize any banks that are found deficient and are unable to issue equity. We can get a sense of how much money is involved by using SRISK to conduct a market-based stress test that measures the banking system’s capital shortfall (from a 5-percent leverage ratio) conditional on a 20-percent decline of the global stock market from its current level. For the 25 banks that have shortfalls using this test, the aggregate shortfall of $103 billion. To give some sense of scale, we performed the same experiment for U.S. banks at the end of March 2009, shortly before the Federal Reserve published the results of its Supervisory Capital Assessment Program. In that case, 27 banks had a total deficiencies exceeding $300 billion. Put differently, the current state of the banking system appears far stronger than it was in 2009, with equity funding needs that are far smaller.

To continue, Congress should reverse the 2018 weakening of regulation. This means imposing routine and appropriately stringent capital and liquidity requirements, as well as stress tests, on all banks with assets in excess of $50 billion. While we can hope that the banks would see the wisdom in this, their previous resistance suggests that they will protest about the cost. But, as everyone can now see clearly, the collective benefits of a stable financial system vastly exceed the private costs of increased scrutiny.

Fourth, we need to revise bank accounting standards. While designing an optimal framework is a complex task that requires substantial further study, fluctuations in the market price of securities on their balance sheets ought to have some influence on banks’ reported capital. Zero impact should not be an option. One easy solution would be for banks, which already report unrealized losses on their securities, to add an “adjusted” measure of their net worth to their disclosures. Making the adjusted measure prominent would improve transparency and, hopefully, spur market discipline.

Finally, there is the issue of resolution. Here, all banks with $50 billion or more in assets need to be subject to resolution planning. The purpose of such plans, which all the largest banks have, is to ensure that failures do not impose public costs (see here). In addition, recent actions have fueled the belief that—in a crisis—all deposits will be insured, not just those up to $250,000. Such blanket deposit insurance could spur banks to increase sharply their reliance on deposits, and lead eventually to much higher public costs from a future crisis. Furthermore, because it is difficult to adjust premiums for risk, raising the cap on deposit insurance likely would encourage bank managers to take more risk in other ways, too. For these reasons, any increase in the cap should result not only in correspondingly higher insurance fees but also in tighter capital and liquidity requirements.

To conclude, SVB’s collapse exposed a series of failures in the financial system. We must now insist on reforms that force banks and supervisors to improve the resilience of individual banks and of the financial system as a whole. It is essential that banks enhance their risk management and disclosures, that authorities improve supervisory practice and resolution planning, and that legislators tighten requirements while providing supervisors with robust tools. Without these changes, the system will remain fragile, and we can expect periods of financial stress to intensify in both frequency and severity.

Acknowledgements: Without implicating them in any way, we are grateful to our friends and colleagues—Viral Acharya, Richard Berner, Alessio De Vincenzo, Matthew Richardson, Paul Tucker, and Lawrence J. White—for their very helpful comments.