Resolution Regimes for Central Clearing Parties

“Central clearing will only make the financial system safer if CCPs themselves are run safely.”

Federal Reserve Governor Jerome H. Powell, June 23, 2017.

Clean water and electric power are essential for modern life. In the same way, the financial infrastructure is the foundation for our economic system. Most of us take all three of these, water, electricity and finance, for granted, assuming they will operate through thick and thin.

As engineers know well, a system’s resilience depends critically on the design of its infrastructure. Recently, we discussed the chaos created by the October 1987 stock market crash, noting the problems associated with the mechanisms for trading and clearing of derivatives. Here, we take off where that discussion left off and elaborate on the challenge of designing a safe derivatives trading system―safe, that is, in the sense that it does not contribute to systemic risk.

Today’s infrastructure is significantly different from that of 1987. In the aftermath of the 2007-09 financial crisis, authorities in the advanced economies committed to overhaul over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives markets. The goal is to replace bilateral OTC trading with a central clearing party (CCP) that is the buyer to every seller and the seller to every buyer. (Exchange-traded derivatives have long cleared through CCPs.)

As we described in an earlier post, shifting all transactions in a class of instruments to a single CCP (sometimes known as a clearinghouse) improves the resilience of the financial system in three important ways. It diminishes the linkages among intermediaries, so that a default of one trading entity is less likely to harm others. It facilitates the enforcement of uniform collateral standards. And, it makes risk concentrations transparent, allowing market participants and the CCP to impose a commensurate risk premium. But, as Governor Powell noted in the speech quoted above, this shift creates a new source of systemic risk: the CCP itself.

In this post, we discuss the challenges authorities face in ensuring that CCPs are safe. The goal, consistent with the recent U.S. Treasury report on capital markets, is to avoid the need for public bailouts.

Before we start, a short note on nomenclature. In recent years the term over-the-counter, or OTC, has come to refer to any transaction that is not on an organized exchange. Our focus here is on the shift from bilateral transactions, where the only firms or individuals involved are the two counterparties to a trade, to transactions that are cleared through a CCP. In current parlance, all these transactions are OTC, so long as they do not occur on an exchange.

How big are the OTC derivatives markets today? The following chart shows the gross notional amounts outstanding. A few points are worth noting. First, since 2013, the reported outstanding volume has fallen by more than $200 trillion to $480 trillion. After adjusting for double counting, we conclude that the amount outstanding has fallen by roughly half. Second, the two largest categories—interest rate swaps and foreign exchange derivatives—account for over 90 percent of the total. Third, while this is not in the chart, the vast majority of these two categories is denominated in either U.S. dollars or euros.

Gross Notional Value of OTC Derivatives Outstanding and Gross Credit Exposure (semiannual, trillions of U.S. dollars), June 1998-December 2016

What fraction of OTC derivatives is centrally cleared? According to the BIS, at the end of 2016, nearly two-thirds of the $440 trillion of interest rate and foreign exchange derivatives was cleared through CCPs. And, that number is rising. (An additional $85 trillion of gross notional principal of exchange-traded derivatives also is centrally cleared.) Unsurprisingly, the largest CCPs report an enormous volume of transactions. For example, LCH Clear and CME Group each currently have outstanding contracts of $30 to $35 trillion in notional value.

This brings us back to Governor Powell’s concern: What happens to a CCP in a period of market stress? What if one fails?

Experience shows that when a CCP fails, financial markets cease to function. In the past, the geographic spillover of these collapses (for example, in the Paris commodities futures market in 1974) was limited by the size of the market or by the lack of cross-border financial integration. However, given the development of the global financial system since 1980, a failure today would have a much broader and more prominent impact.

As a result, the design of CCPs has been a principal focus of post-crisis regulatory reform. While this has not attracted the same attention as banking system reform, international authorities have been hard at work developing and promulgating principles to guide the functioning of these enormous financial intermediaries (see here and here).

Are the resulting safeguards sufficient?

To answer this question, start by recalling that a CCP has a matched book―for each short position there is an identical offsetting long position. Having a zero net position means that the CCP is without risk so long as its counterparties remain viable and can make good on their contracts.

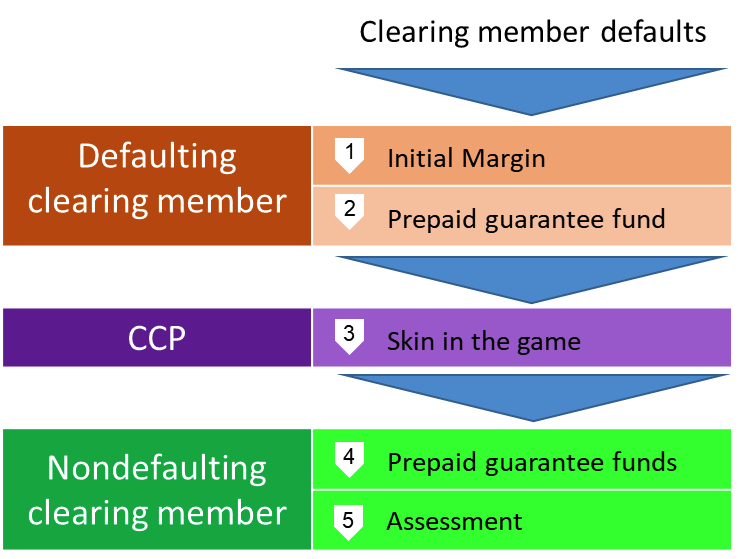

But, what if one or more large counterparties to the CCP cannot perform? The graphic below depicts the typical waterfall of backstops in the event of such a failure.

Typical CCP Default Waterfall

Source: Treasury Office of Financial Research, Figure 1.

The first line of defense is margin (sometimes referred to as a “performance bond”). To enter into a derivative contract, both parties need to supply margin. Each day, the CCP then posts gains and losses to the margin account of the two sides to the transaction. That is, whenever the price of the contract changes, the losers must pay the winners at least overnight. To make these payments, the CCP may need to ask for resources from the parties to the trade. Depending on the CCP’s rules, these variation margin calls can occur more than once per day.

What if a trader fails to meet a margin call? Each member of the CCP—every institution that engages in transactions—is required to contribute to a guarantee fund. (The members are the firms that implement the trades through the CCPs, not individual investors. For example, the CME Group lists 70 clearing firms. ) If a clearing firm defaults, and the margin is not sufficient to meet the payment obligation, that firm’s guarantee fund contribution is the second line of defense.

Once the defaulting firm’s own resources at the CCP—margin plus guarantee fund contribution--are exhausted, others contribute. This starts with the CCP’s own capital. Next, comes the guarantee fund contributions of other members. And, finally, the CCP has a loss-sharing arrangement among its members—ex post assessments—where everyone is required to contribute once all the other backstops are used up. Yet, it is precisely in a crisis—when such assessments would be most likely to occur—that CCP members would be least able to comply.

We looked at the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) to get a sense of the size of each of these slices. According to its annual disclosure, at the end of 2016, the CME held total margin of $150 billion against open interest with a U.S. dollar equivalent notional value of roughly $30 trillion. As background, margin requirements typically depend on the price volatility of the underlying security. A standard calculation would be that the margin should cover 99 percent of price movements over the past 250 days. (For indicative calculations, see here.)

The next two slices of protection—the clearing members’ contribution to the prepaid guarantee fund and the CME’s own capital—are $7 billion and $300 million, respectively. Finally, the potential assessments add an additional $12 billion. (Data on the CME’s financial safeguards are here, and additional information is in the quantitative disclosures here.)

Are these various layers of loss absorption thick enough to sustain operations in a period of system-wide stress?

At first glance, the numbers are not encouraging. Margin, the pre-paid guarantee fund, and the CCP’s own contribution are 0.5%, 0.02% and 0.0007% of notional gross open interest, respectively. It does not seem as if it would take an unprecedented market move to wipe this all out.

The vulnerability of CCPs has not escaped authorities. To manage systemic risk from these behemoths, supervisors have taken the obvious approach: stress testing. In November 2016, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) published the results of its first supervisory stress tests of clearinghouses. Included in the tests are the five entities—including two located in London—that account for 98 percent of futures and swap clearing registered in the United States.

To stress test the CCPs, the CFTC started by creating a set of 11 scenarios that include different combinations of volatility across markets. For each scenario, positions are marked-to-market. The CFTC test assumes that no clearing member can respond to a variation margin call, so a member defaults when the sum of its existing margin plus its contributions to the guarantee fund is exhausted. Supervisors then compute the number of member defaults that a clearinghouse can withstand before exhausting its resources, without resorting to assessments. The clearinghouses passed under two-thirds of the scenarios. (We have been unable to find disclosures by the CFTC or by the clearinghouses of the detailed results—for example, which clearinghouses passed which tests and by how much.)

Should we be worried? How likely is it that a CCP will run out of resources? In that situation, what happens next?

Several people have suggested mechanisms for resolving a failing CCP, and the Financial Stability Board has weighed in as well. However, in the midst of a crisis, we suspect that governments would be more likely to bail out a CCP than to impose resolution procedures. To maintain the function of the financial system, whatever happens to the CCP would have to happen overnight, or even intraday. Promises to foreswear a bailout in favor of a slow resolution procedure, or one that requires a private recapitalization during a crisis, lack credibility (and time consistency).

While clear resolution procedures are surely desirable, our primary goal should be to ensure the resilience of the CCP, making failure and the need for a bailout exceedingly remote. One way to do this is to reverse the stress test procedure (something the CFTC mentions at the end of their stress test report). Rather than examining whether the CCP can withstand a particular scenario, we should ask how bad financial conditions have to get before the CCP fails, and then assess the likelihood of this failure scenario. Such a reverse stress test could tell us about the probability of a bailout. If legislators and regulators view that probability as too high, the remedy is to compel an increase in the CCP’s buffers—the combination of margin, the guarantee fund and the CCP’s own capital—until the probability falls to an acceptable threshold.

The key point is that we should be transparent about the very limited circumstances—such as outright war—when we expect the government to step in to keep the water flowing, the electricity running, and the financial system operating. The clearer we are about these conditions, the greater the incentive we will have to make sure that the financial system—including systemic CCPs—operates safely without government aid nearly all of the time.