The Fed Goes to War: Part 1

“This is no war of chieftains or of princes, of dynasties or national ambition; it is a war of peoples and of causes. There are vast numbers, not only in this island but in every land, who will render faithful service in this war but whose names will never be known, whose deeds will never be recorded. This is a war of the Unknown Warriors; but let all strive without failing in faith or in duty….” Winston Churchill, BBC Broadcast, London, 14 July 1940.

Over the past two weeks, the Federal Reserve has resurrected many of the policy tools that took many months to develop during the Great Financial Crisis of 2007-09 and several years to refine during the post-crisis recovery. The Fed was then learning through trial and error how to serve as an effective lender of last resort (see Tucker) and how to deploy the “new monetary policy tools” that are now part of central banks’ standard weaponry.

The good news is that the Fed’s crisis management muscles remain strong. The bad news is that the challenges of the Corona War are unprecedented. Success will require extraordinary creativity and flexibility from every part of the government. As in any war, the central bank needs to find additional ways to support the government’s efforts to steady the economy. A key challenge is to do so in a manner that allows for a smooth return to “peacetime” policy practices when the war is past.

In this post, we review the rationale for reintroducing the resurrected policy tools, distinguishing between those intended to restore market function or substitute for private intermediation, and those meant to alter financial conditions to support aggregate demand.

Constraints on the Fed. Before we get to the details, we should highlight two constraints affecting central bank policy in the United States. The first involves what the Fed can own, and the second concerns to whom they can lend. On the first, the Federal Reserve Act effectively limits what the central bank can purchase to Treasuries or instruments guaranteed by the federal government (see Section 14 (2) of the Federal Reserve Act). As Clouse and Small note, the Fed has “no express authority” to acquire corporate bonds, bank loans, mortgages, credit card receivables, or equities. Put differently, the Fed generally cannot acquire domestic securities with credit risk, although they can lend against them as collateral.

Second, in normal times, the Fed can lend only to banks. During the Great Financial Crisis, the Fed lent to almost anyone in its role as lender of last resort (see Section 13 (3) of the Federal Reserve Act). The Dodd-Frank Act narrowed this emergency authority, replacing the bracketed portion of the text with the words in bold:

“In unusual and exigent circumstances, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System…, may authorize any Federal reserve bank … to discount [for any individual, partnership, or corporation] for any participant in any program or facility with broad-based eligibility, notes, drafts, and bills of exchange …. The Board may not establish any program or facility under this paragraph without the prior approval of the Secretary of the Treasury.” (For a discussion see here.)

As a result, the Treasury Secretary must now approve of any program for lending to nonbanks, while the Fed can no longer lend to individual nonbanks (as they did repeatedly in 2008). The practical implications of this change appear limited so far: over the past week, with the approval of the Treasury Secretary, the Fed has re-started several programs and facilities with broad-based eligibility. Indeed, by creating a special purpose entity, the Fed can lend to support the purchase of assets (including equities) that it lacks authority to buy directly.

Stabilizing the Financial System: Ensuring Liquidity and Market Function. The Fed has two stabilization objectives. The first is medium-term economic stability: keeping inflation and unemployment low and stable. The second is financial stability. Originally, in its role as lender of last resort, the Fed focused on supporting solvent, but illiquid banks (see our primer). Today, however, nonbanks conduct nearly two thirds of U.S. intermediation. Furthermore, some of these entities are subject to runs due to their roles in transforming liquidity and maturity—something we have known about but failed to repair for years. Consequently, the Fed’s financial stability role has expanded to include the restoration of market function and the substitution for the loss of private intermediation resulting from the crisis.

Keep in mind that central banks have the capacity to act very quickly and that they can increase the size of their balance sheet without limit. Where central banks substitute for private intermediation, either through the direct purchase of assets or by lending to institutions holding certain assets, their actions may involve increases in both the quantity and the riskiness of what they own. The purpose of the action is to deliver liquidity where it is needed in the volume needed as quickly as possible. In contrast, increases in the size of the balance sheet that are limited to traditional low-risk, short-maturity Treasuries—what we call quantitative easing (QE)—constitute a monetary policy tool that may be used even in periods of financial stability in order to ease financial conditions when conventional policy rates are at zero.

Comparing Current and Earlier Crisis Policy Actions. We now compare the policy actions of the past two weeks with those of the 2007-09 episode, starting with monetary policy. Rather than reducing the target federal funds rate close to zero over a period running from September 2007 to December 2008, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) completed the trip in two weeks. Second, mimicking the Fed’s balance sheet explosion following the Lehman failure, policymakers immediately announced their intention to purchase $700 billion in Treasuries and federally guaranteed mortgage-backed securities. This mix of QE (balance sheet expansion) and targeted asset purchases (TAP) clearly aims at supporting prices and lowering yields on long-term safe debt. (The two tables at the end of this post provide a chronology of key Federal Reserve actions in March 2020 and during the 2007-09 period.)

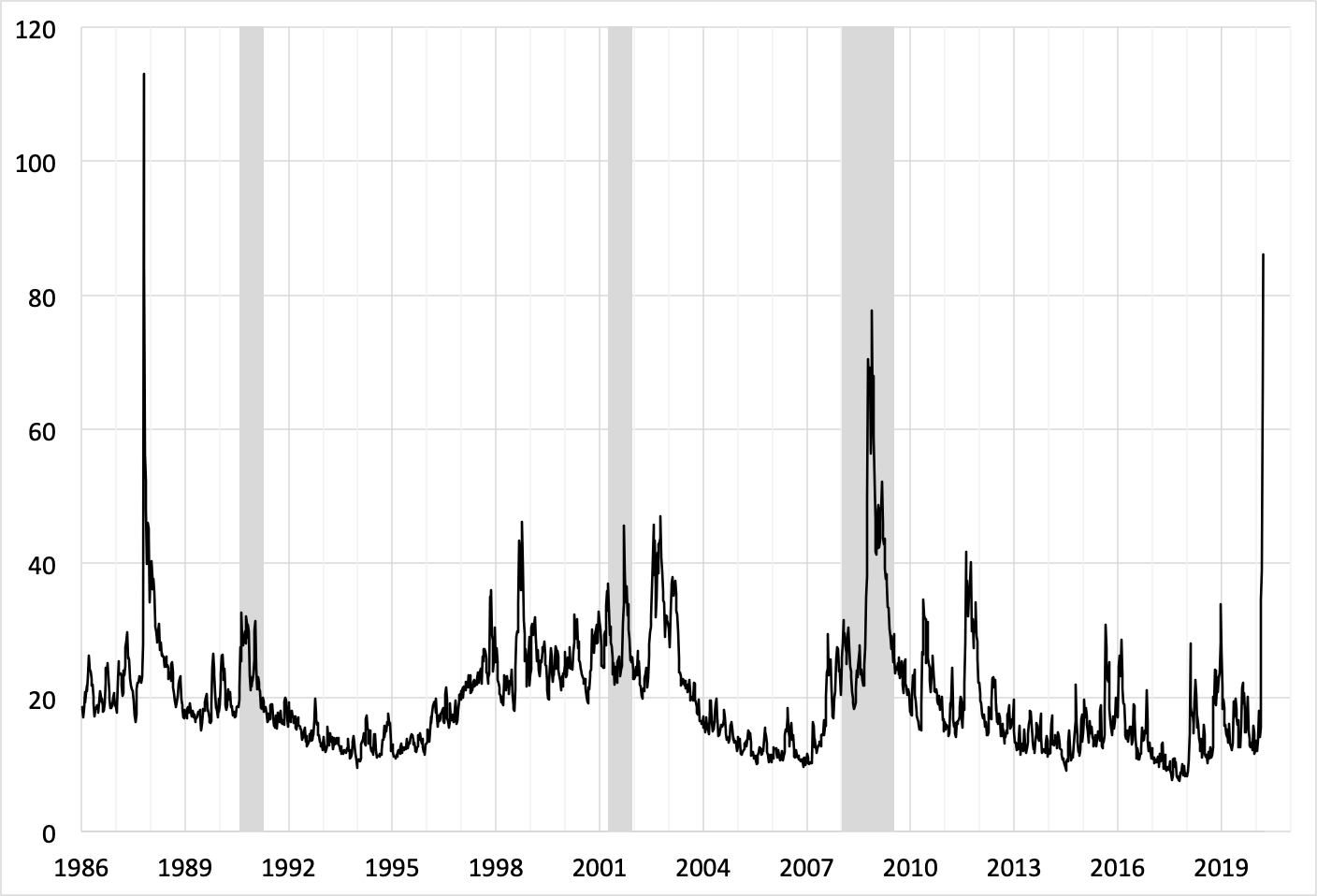

The actions to promote financial stability were both more numerous and more complex. The reason is that the challenges here are enormous. The following figure shows the volatility index for the S&P 100. While below the October 1987 peak of 113, the most recent week’s average of 86 surpassed the peak during 2007-09 crisis.

CBOE S&P 100 volatility index (weekly average), 1986 to March 20, 2020

Note: Recessions shaded in gray. Source: FRED.

Turning to specifics, first, in a straightforward expansion of the program they started in September 2019, the Fed offered repo funding of up to $1.5 trillion to stabilize short-term funding markets.

Second, the FOMC revitalized the U.S. dollar liquidity swap facilities with foreign central banks. The goal is to ensure adequate funding for the enormous Global Dollar System outside the United States without burdening the Fed with foreign private counterparty risk. Armed with dollar funding, foreign central banks who “know their customers” can on-lend the dollars to solvent domestic intermediaries. In 2007-08, it took nearly 10 months for the Fed to develop these central bank swap lines. This time, the FOMC simply jumped to the status at the height of the earlier crisis: 14 central banks are eligible; where there were volume limits, they raised the limits; and where the facilities were unlimited, they appear to be unlimited again.

Next, comes the re-introduction of programs and facilities created between 2007 and 2009. On the Board’s website, under “Monetary Policy: Policy Tools”, there is a list of current tools. Until March 17, there were six current tools (Open Market Operations, Discount Window, Reserve Requires, Interest on Reserves, Overnight Reverse Repurchases, and Term Deposits). Furthermore, if you clicked through to the “Expired Policy Tools,” you would have found a list of nine. Over the past week, three of the expired tools rose from the dead. These are the Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF), the Primary Dealer Credit Facility (PDCF), and the Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility (MMLF).

The current incarnation of these three facilities includes notable changes that reflect the benefits of experience. First, the CPFF and the MMLF have credit protection from the Treasury. That is, these now have an explicit fiscal component. As the Fed lends to a special-purpose vehicle that acquires commercial paper (CPFF) or to institutions that acquire assets from money market funds, the Treasury backstop of $10 billion will allow the Fed to accept the credit risk from less-than-pristine collateral. While the new PDCF lacks such a taxpayer backstop, it allows the Fed to lend against a broad range of collateral—including equities. This last part mimics the post-Lehman broadening of the original PDCF.

The rationale for each of these is straightforward. Starting with the CPFF, while the quantity of commercial paper today is roughly half the $2.2 trillion at the peak in August 2007, CP remains an important method of short-term finance for investment-grade firms. Issuers typically count on their ability to rollover outstanding issues to maintain working capital. With a weighted average maturity of just under two months and between $50 and $200 billion maturing every week, this market is both essential and fragile (see here).

Turning to the PDCF, primary dealers act as market makers for a variety of financial instruments. Importantly, they are key participants in the issuance of U.S. Treasury debt. Unless market makers are liquid, markets will become illiquid. Lending to primary dealers against a broad range of collateral helps to maintain market function, especially in an episode (like the current one) of extreme volatility.

Next, there is the MMLF. Here, something we saw in 2008 appears to have come back in full force: a run on prime money market funds (see here and here). To allow the money market funds to meet heightened withdrawals without a fire sale of their assets, the Fed has chosen to lend to financial institutions that purchase the short-term holdings (such as commercial paper) of the prime funds. What is particularly shocking about this is that we really did know better. Money market funds are simply specialized banks and we should treat them as such. As we discuss in an earlier post, the SEC’s changes did not fix the problem.

The Fed’s website still lists six expired tools that may not return. For example, the new MMLF is already backstopping money markets, so there seems to be little need for a Money Market Investor Funding Facility. Similarly, with the level of asset-backed commercial paper down by more than 75 percent from its 2007 peak, there is little reason to resurrect the ABCP MMMF Liquidity Facility. Finally, with the Fed encouraging banks to borrow using the discount window—credit is now at the highest level since 2009—it is unclear that there are any benefits to re-introducing the Term Auction Facility.

All that said, the longer the upheaval, the more widespread the likely disruptions for financial markets and intermediaries alike. While we may not see old programs or facilities return, we expect that the Fed staff is working furiously and creatively to fashion new tools just in case.

What’s next, and for whom? This brings us to the question of the moment: How far should the Fed go?

In their recent statement entitled “Proposed Measures to Address Economic Elements of Current Pandemic Crisis, the Systemic Risk Council argues that central banks should “Prepare for and, where necessary, promptly conduct wider outright purchase of private securities (and, in jurisdictions where this is necessary, for such purchases to be guaranteed by governments).” We agree in principle that such interventions can be legitimate in wartime. However, we question whether the Federal Reserve is the proper institution to implement them.

In the U.S. system, assuming they have Congressional authorization to use taxpayer funds for this purpose, the Treasury is the natural government agent to purchase private securities. Were the Treasury finding it costly to finance such an intervention, the Fed could help. At the moment, however, one-year Treasury bill rates yield 0.13%, virtually identical to the 0.10% rate that the Fed pays overnight on reserves, so there is little difference the two. If the Treasury needed expertise to manage these assets, they could turn to the private sector (much as the Fed did in 2008 when it announced plans to acquire mortgage-backed securities).

Our concern is with the legitimate and sustainable delegation of authority in a democracy. Given the distributional consequences associated with the purchase of private equity or debt, Congress and the President should explicitly authorize and allocate funds for any government acquisition. And, since this can be viewed as a form of partial nationalization, we doubt that the central bank—which needs to preserve its independence in peacetime—should be directly involved. Importantly, limiting the credit risk on the balance sheet of the central bank (even if there are fiscal guarantees) makes exit easier when the time comes. Even when credit risk is absent, think of how the distributional consequences of selling mortgage-backed securities (MBS) make it so much easier to shrink holding of Treasurys.

What role could the Fed play? As it did during WWII, they could offer to maintain low financing costs on the required debt issuance for some period. Importantly, the entirety of the financing need not be in the form of reserves. Instead, the Fed could act as a backstop were private demand for the federal debt to freeze. Admittedly, however, if the Fed were to become the residual buyer of Treasury issues, this would be fiscal dominance pure and simple. Put differently, helicopter money is fiscal policy carried out with the cooperation of the central bank.

To be clear, we see the fight to steady the economy in the face of the pandemic much as Churchill saw mobilization in wartime (see the opening quote). In this case, the adversary is a virus that is attacking our physical and economic well-being. This makes cooperation between the central bank and the government essential. And, that cooperation should be based on a shared incentive: restoring the financial system and economy as close as possible to the status quo ante bellum. For now, this leaves the Fed in a position to support wartime finance. In doing so, however, we should let elected officials take on those interventions that are most distributional in character. This will make it feasible to return to central bank independence quickly in peacetime.

NOTE: A PDF version of the following annexes is here.

ANNEX 1: Monetary and Financial Stability Policy Actions, March 3 to March 20, 2020

March 3

Interest rate target range cut of 50 basis points. Interest rate on excess reserves cut from 1.6% to 1.1%, and discount rate cut from 2.25% to 1.75%. (See here and here.)

March 9

Increase amount offered in overnight repo agreements from at least $100 billion to at least $150 billion. Increase amount offered in two-week term repo agreements from at least $20 billion to at least $45 billion. (See here.)

March 11

Increase of overnight repo to $175 billion. (See here.)

March 12

Offer $500 billion in three-month repo, and $500 billion in one-month repo. (See here.)

March 15

Interest rate target range cut of 100 basis points. Interest on excess reserves cut from 1.1% to 0.1%, and discount rate from 1.75% to 0.25% (see here and here).

Discount loans of up to 90 days, renewable daily (see here).

Encourage uncollateralized intraday credit (see here).

Encourage banks to use capital and liquidity buffers to maintain credit supply (see here).

Eliminate reserve requirements (see here).

Purchase at least $500 billion in Treasurys and $200 billion in agency MBS. “The FOMC instructed the Desk to conduct these purchases at a pace appropriate to support the smooth functioning of markets for Treasury securities and agency MBS.” (See here.)

Offer $500 billion in one-month term repo and $500 billion in three-month term repo each week (see here).

Lower the interest rate on U.S. dollar liquidity swap arrangements with Bank of Canada, the Bank of England, the Bank of Japan, the European Central Bank, and the Swiss National Bank by 25 basis points; and in return, the foreign central banks agreed to lengthen the maturity of the dollar loans to their banks (see here). Note that liquidity swap arrangements have been in place since October 2013.

March 16

Encourage commercial banks to borrow from the Federal Reserve (see here).

March 17

Further encourage commercial banks to use capital and liquidity to maintain credit supply (see here).

Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF): Under authority of Section 13 (3) of the Federal Reserve Act, with the approval of the Secretary of the Treasury, established a special purpose vehicle (SPV) to purchase unsecured and asset-backed CP rated A1/P1 (as of March 17, 2020) directly from eligible companies. The Treasury will provide $10 billion of credit protection to the Federal Reserve from the Treasury's Exchange Stabilization Fund (ESF). (See here, and note the terms and conditions.)

Primary Dealer Credit Facility (PDCF): Under authority of Section 13 (3) of the Federal Reserve Act, with the approval of the Secretary of the Treasury, established a facility to offer overnight and term funding of up to 90 days to primary dealers. Credit extended to primary dealers under this facility may be collateralized by a broad range of investment-grade debt securities, including commercial paper and municipal bonds, and a broad range of equity securities. (See here, and note the term sheet.)

March 18

Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility (MMLF): Under authority of Section 13 (3) of the Federal Reserve Act, with the approval of the Secretary of the Treasury, establish a facility to “make loans to eligible financial institutions secured by high-quality assets purchased by the financial institution from money market mutual funds.” The Treasury will provide $10 billion of credit protection to the Federal Reserve from the Treasury's Exchange Stabilization Fund (ESF). (See here, and note the term sheet.)

March 19

Established U.S. dollar liquidity swap arrangements of $60 billion each for the Reserve Bank of Australia, the Banco Central do Brasil, the Bank of Korea, the Banco de Mexico, the Monetary Authority of Singapore, and the Sveriges Riksbank; and $30 billion each for the Danmarks Nationalbank, the Norges Bank, and the Reserve Bank of New Zealand. (See here.)

Note the increase in discount borrowing during the week. (Weekly data released that afternoon showed a rise from $11 million to $28.2 billion; see also here.)

March 20

Enhanced the MMLF to allow loans to “eligible financial institutions secured by certain high-quality assets purchased from single state and other tax-exempt municipal money market mutual funds.” (See here.)

Note: Some domestic monetary policy actions were authorized by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) and others the Federal Reserve Board. Regulatory actions were coordinated among domestic agencies, including the Federal Reserve Board. Decisions on U.S. dollar swap facilities rest with the FOMC.

Source: Federal Reserve press releases.

ANNEX 2: Monetary and Financial Stability Policy Actions, December 2007 to April 2009

December 12, 2007

Established the Term Auction Facility (TAF) to “auction term funds to depository institutions against the wide variety of collateral that can be used to secure loans at the discount window.” (The TAF continued to auction reserves through March 2010.)

Authorized U.S. dollar liquidity swaps of $20 billion with the European Central Bank and $4 billion for the Swiss National Bank. (See here.)

March 7, 2008

Increased the amount of the TAF to $50 billion per week.

Offered 28-day term repo agreements of up to $100 billion. (See here.)

March 11, 2008

Announced creation of Term Securities Lending Program (TSLF), as an expansion of the existing securities lending program.

Increased the swap lines for the ECB and the SNB to $30 billion and $6 billion. (See here.)

March 16, 2008

In connection with the proposed JPMC/Bear Stearns acquisition, and given the unusual and exigent circumstances, the Board authorized the New York Fed to make a nonrecourse loan of up to $30 billion that would be fully collateralized by a pool of Bear Stearns assets. (See here.)

The Secretary of the Treasury supported the action and acknowledged that any loss arising from the loan could be treated as an expense that would reduce earnings the Fed transfers to the Treasury. (See here.)

Under authority of Section 13 (3) of the Federal Reserve Act, created the Primary Dealer Lending Facility (PDCF) to provide overnight funding in exchange for collateral including “all investment-grade corporate securities, municipal securities, mortgage-backed securities and asset-backed securities for which a price is available.” (See here and here.)

Reduced the discount rate from 3.5% to 3.25% (See here.)

March 18, 2008

Reduced the federal funds rate target by 75 basis points to 2.25% and the discount rate from 3.25% to 2.5%. (See here and here.)

April 30, 2008

Reduced the federal funds rate target by 25 basis points to 2% and the discount rate from 2.5% to 2.25%. (See here and here.)

July 30, 2008

Extended the term of the PDCF and TSLF. (See here.)

September 14, 2008

Broaden collateral eligible under PDCF and TSLF. (See here.)

September 16, 2008

Under authority of Section 13 (3) of the Federal Reserve Act, extended $85 billion in credit to the American International Group (AIG). The loan amount increased by $37.8 billion on October 6. (See here.)

September 18, 2008

Authorized expansion of U.S. dollar liquidity swap facilities to $110 billion for the ECB and $27 billion for the SNB. In addition, authorized facilities of $60 billion for the Bank of Japan, $40 billion for the Bank of England, and $10 for the Bank of Canada. (See here.)

September 19, 2008

Under authority of Section 13 (3) of the Federal Reserve Act , created the Asset-Backed Commercial Paper Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility (AMLF) to provide funding to U.S. depository institutions and bank holding companies to finance their purchases of high-quality asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP) from money market mutual funds. (See here and here.)

Provided certain exceptions to capital rules and restrictions on transactions between banks and their affiliates. (See here.)

September 24, 2008

Authorized U.S. dollar liquidity swap facilities with the Reserve Bank of Australia and the Sveriges Riksbank of $10 billion each; and with the Danmarks Nationalbank, and the Norges Bank for $5 billion each. (See here.)

September 26, 2008

Further expanded the U.S. dollar liquidity swap facilities to a total of $290 billion. (See here.)

October 3, 2008

Under authority of Section 13 (3) of the Federal Reserve Act, created the Direct Money Market Mutual Fund Lending Facility (DMLF) to allow funding directly to Money Market Mutual Funds. (See here.)

October 6, 2008

Announce the payment of interest on excess reserves, initially set at the federal funds rate target less 75 basis points. (See here.)

October 7, 2008

Under authority of Section 13 (3) of the Federal Reserve Act, created the Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF), a special purpose vehicle that will purchase commercial paper. (See here.)

October 8, 2008

Reduced the target federal funds rate by 50 basis points to 1.5%, the discount rate to 1.75%,

October 13, 2008

Increased the U.S. dollar liquidity swap facilities with the Bank of England, the European Central Bank, the Swiss National Bank and the Bank of Japan to make them unlimited. (See here and here.)

October 20, 2008

Fed and other bank regulators encourage participation capital purchase program and FDIC’s Temporary Liquidity Guarantee Program (see here)

October 21, 2008

Under authority of Section 13 (3) of the Federal Reserve Act, created the Money Market Investor Funding Facility (MMIFF) to provide funding to money market mutual funds. (See here and here.)

October 28, 2008

Authorized U.S. dollar liquidity swap facility for up to $15 billion with the Reserve Bank of New Zealand. (See here.)

October 29, 2008

Reduced the federal funds rate target by 50 basis points to 1% and the discount rate from 1.75% to 1.25%.

Authorized U.S. dollar liquidity swap facilities of up to $30 billion each by the Banco Central do Brasil, the Banco de Mexico, the Bank of Korea, and the Monetary Authority of Singapore. (See here.)

November 23, 2008

Under authority of Section 13 (3) of the Federal Reserve Act, authorized conditional credit to Citigroup (see here).

Under authority of Section 13 (3) of the Federal Reserve Act, created a Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility (TALF). The TALF would lend on a non-recourse basis to “holders of certain AAA-rated ABS backed by newly and recently originated consumer and small business loans.” The Treasury will provide $20 billion of credit protection to the Federal Reserve from the Treasury's Exchange Stabilization Fund (ESF). (See here and here, as well as the term sheet.)

November 25, 2008

Announced a program to purchase up to $100 billion worth of the direct obligations of the housing-related Government Sponsored Entities (GSEs) and $500 billion in MBS. The purchases would be through asset managers. (See here.)

December 16, 2008

Reduced the federal funds rate target to a range of 0 to 0.25%, and the discount rate to 0.50%. (See here and here.)

January 07, 2009

Expanded eligibility for the Money Market Investor Funding Facility (MMIFF). (See here.)

January 15, 2009

Agreement with Bank of America (involving Fed, Treasury and FDIC) to guarantee or lend against a pool of $118 billion in assets. (See here.)

Feb 10, 2009

Announced willingness to expand the size of the Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility (TALF) to as much as $1 trillion. (See here.)

Feb 23, 2009

Announcement of the Supervisory Capital Assessment Program (stress tests). (See here.)

April 6, 2009

The Bank of England, the ECB, the Bank of Japan and the Swiss National Bank announce liquidity swap facilities in their currencies with the Federal Reserve. (See here.)

Note: Some domestic monetary policy actions were authorized by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) and others by the Federal Reserve Board. Regulatory actions were coordinated among domestic agencies, including the Federal Reserve Board. Decisions on U.S. dollar swap facilities rest with the FOMC.

May 7, 2009

Release of results of the Supervisory Capital Assessment Program (stress tests). (See here.)

Note: Some domestic monetary policy actions were authorized by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) and others the Federal Reserve Board. Regulatory actions were coordinated among domestic agencies, including the Federal Reserve Board. Decisions on U.S. dollar swap facilities rest with the FOMC.

Source: Federal Reserve press releases.